Terrorist group Boko Haram demands the adoption of sharia throughout Nigeria, though it has been practised in 12 Muslim-dominated states in the north since the fall of military rule in 1999. Is sharia as practised in Nigeria compatible with democracy and the protection of the rights of women and minorities?

Ethnicity was Nigeria’s dominant fault line in the years after its independence from Great Britain in 1960. Religion played second fiddle. However, as the 20th century trundled to a close, religion gained ascendancy, becoming Nigeria’s dominant tinderbox. Ethnicity took a back seat.

In the years preceding this change of baton, major upheavals in Nigeria, including a bitterly-fought civil war, had ethnic roots. Religious tension simmered beneath the Nigerian socio-political firmament but the authorities squelched clashes between adherents of the country’s two dominant religions—Christianity and Islam— before they got out of hand.

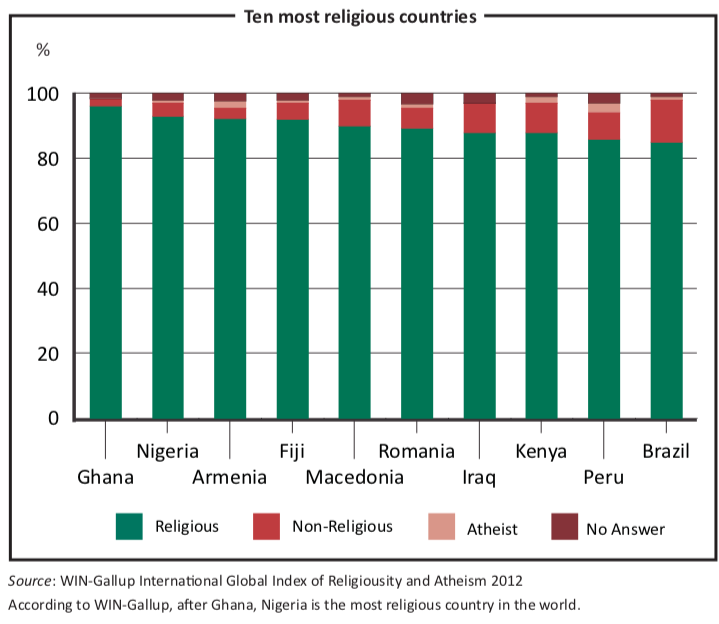

With the advent of democracy and greater freedoms, religious tensions long kept at bay are rising to the surface. Analysts have said that what ethnicity was to Nigeria in the last century, religion might be in the current one. A WIN-Gallup International poll in August concluded that Nigeria was, after Ghana, the most religious country in the world.

Nigeria’s constitution defines it as a secular country and forbids the adoption of a state religion. But many Nigerians insist that their country is multi-religious. A 2011 study by the Pew Centre, a United States-based research organisation, estimated the population of Christians in Nigeria to be 80m and Muslims 76m. Poignantly, it also acknowledged the volatile nature of religion in Nigeria. “Because the proportion of Muslims and Christians in Nigeria is a sensitive political issue, the national census has not asked questions about religion since 1963,“ the study said.

Certain recent developments have increased this volatility. The first is a revival of proselytising fundamentalist Pentecostalism. The second is a resurgence of extremist Islamism, especially a low-level insurgency waged by a local terrorist group, Boko Haram. Third are the conflicts that have arisen from the implementation of sharia in parts of the country.

Sharia is not new to Nigeria. Islam arrived here 700 years ago, through itinerant preachers and traders who trod the trans-Saharan trade route that connected the fringes of the Sahel with ancient Arabia. Sharia followed in its footsteps. Except for a break during the colonial era, when the British replaced its criminal law aspects with the penal code, sharia was the major ordinance, which moderated social, economic and political activities in the region.

In 1999, Zamfara, a northern state with a Muslim majority, enacted legislation adopting sharia as its legal code. By 2001, 11 more states in the region had followed suit. The adoption brought the new law into conflict with the Nigerian constitution which, ordinarily, supersedes all state laws. Although averse to the adoption, the federal government was wary of the religious crisis that a forced reversal would induce. So, it dithered.

The consequence is that these states now operate sharia side-by-side with the penal code. Sharia is only meant to be applied in cases involving Muslims who agree to its jurisdiction. However, non-Muslims in the states have complained about the sharia task forces whom they claim harass, intimidate and apply sharia to non-Muslims. But the authorities and the Muslim majority have ignored these complaints.

Despite the predominance of Islam in the North, the region is also home to a substantial and vocal minority of religious, racial and sexual groups. They and the international community have long criticised the aspects of sharia that prescribe punishments like stoning for adultery and amputation for theft. They have also described the implementation of the law in Nigeria as skewed against minorities and women.

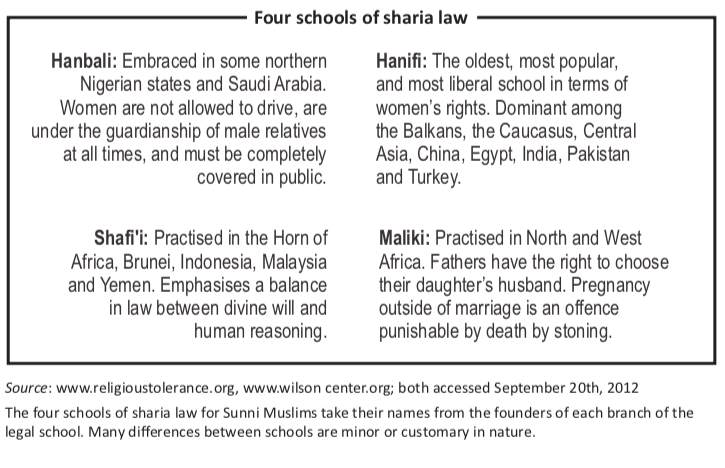

In “Written in Stone? The Impact of Sharia Law on Women’s Rights in Nigeria”, Susan Courtwright traces the problem to the peculiarities of sharia jurisprudence favoured by scholars and traditions. The Maliki school, which is the strictest of the four schools of sharia thought, is particularly harsh on minorities and women, Courtwright writes. “The spirit of the Koran and other texts and teachings of Islam have provisions to protect women’s basic rights, but the Maliki interpretation of sharia, as applied in northern Nigeria, often fails to protect these rights,” she says. Some reformists agree.

Almost on a daily basis, the skewed implementation of sharia in the north throws up cases that provide fodder for critics. In 2001, a sharia court in Sokoto convicted Safiya Hussaini, a 35-year-old divorcee, of adultery and sentenced her to death by stoning. The evidence? Pregnancy outside wedlock. A year later, Amina Lawal, a 30-year-old uneducated divorcee, was also sentenced to lapidation, on the grounds of adultery, after having a child out of wedlock. In both cases, the men who had sex with the women were acquitted for lack of evidence. Both convictions were eventually quashed on appeal after extensive media coverage and public outrage applied considerable pressure on the Nigerian government and the judiciary.

As usual with the few well-publicised cases involving minorities under sharia, the Hussaini and Lawal cases pitted two sides of the sharia debate against each other. On one side was a coalition of local and international media commentariat, foreign governments and civil society. This group argues that sharia is inimical to democratic ideals and human rights and wants it set aside.

On the other are the proponents of sharia, who see it as an infallible divine code that is beyond reproach or reform. This group views advocacy as meddlesomeness, or at worst, a form of cultural imperialism. Nigerian Muslims, government officials and Islamic jurists make up this group, which often insists that all sharia rulings should be enforced.

Whenever the groups lock horns, emotions run high, perspectives narrow and the key issues are often obfuscated. An old African proverb captures the ensuing stand- off and the plight of minorities: it is the grass that suffers when two elephants fight. But this need not be.

Is sharia law, especially the variant applied in Nigeria, compatible with democratic ideals and human rights? Yes, it is—but only partly. A good study of the system would reveal similarities between its spirit and the Judeo-Christian principles upon which the common law is based. Proponents agree that aspects of sharia law, as applied in Nigeria, are in dire need of reform.

In the face of criticism, proponents have argued that the spirit of sharia promotes justice, equality and societal orderliness. Opponents have premised their opposition to sharia on the same principles. What then becomes clear is that meeting points should, and indeed, do exist, and should be explored. Such points include sharia provisions that protect the rights of minorities and women, public initiatives to highlight and educate the public about these provisions and community-based efforts that would provide cheap legal representation for minorities and women.

Hauwa Ibrahim, Ms Hussaini’s lawyer, adopted this centrist approach. Showing remarkable insight into the workings of the sharia system in Nigeria, Ms Ibrahim realised that a media battle on the propriety of sharia law would not serve her client well. Rather, she developed a successful strategy that mixed a tempered media campaign with a courtroom battle on the failure of the prosecution to provide her client with the protections the Islamic legal code offers the accused.

Critics may assail this approach as conciliatory. Yet, it remains the most effective short-term approach to obtaining justice for minorities in countries where sharia enjoys considerable support. Traditions and mores built over centuries are not likely to change in a hurry.

If the damage done to the rights of minorities and women is to be mitigated in the long term, opponents and proponents of sharia must find common ground on which they can stand together.

For inspiration, they could look in the direction of an 18th century poet, Islamic scholar, writer and philosopher king, Muhammadu Bello. Mr Bello was the son and successor of Othman Dan Fodio, the Fulani Islamic preacher who founded the great Sokoto caliphate which covered today’s northern Nigeria, parts of Cameroon and Niger.

Mr Bello wrote extensively on these matters as if he had modern Nigerian sharia law in mind. He is also one of the inspirations for respected Nigerian academic Muhammad Ladan and other crusaders’ call for reforms. According to Professor Ladan, Mr Bello wrote that the state “is permitted to ignore the letter of the law in favour of the spirit if the occasion so demands. It is only in this way that the fundamental objectives of the sharia can be realised, and the interests of humanity in general, and the Muslims in particular, safeguarded.”