Tertiary education is on life support

by Adeyeye Joseph

At a protest last July at the University of Ibadan in south-western Nigeria, a student brandished a placard that complained, “Education is dead in Nigeria.”

The demonstrators were from Nigeria’s oldest university, founded in 1948. They had taken to the streets to demand an end to a lecturers’ strike that had grounded academic activities in all but two of Nigeria’s 78 public universities. The strike was in its third week when the protest took place. The message on the placard was both a plea for the lecturers to return to work, and an attempt to draw attention to the state of education in Nigeria.

The lecturers’ strike, the third in four years, pitted the academics against the owners of Nigeria’s public universities—the country’s central and state governments. The trade dispute centred on a wide-ranging agreement between the two parties, concluded in 2009 at the end of a four-month lecturers’ strike. The agreement provides for greater funding of public universities, better wages for lecturers and a declaration of a state of emergency in the tertiary education sector. The lecturers’ union, the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU), now accuses the government of reneging on the terms of the 2009 agreement.

“Strike has always been an option of last resort for the union,” explained Nasir Fagge, ASUU chairman, during an interview with a Nigerian newspaper, Daily Trust. “We have had almost close to 50 meetings with government at several levels” between 2010 and 2013, he added. “We have been lobbying to ensure that we avert this crisis, but it became clear to us that the dialogue was between the deaf and the dumb, and under such a circumstance we did not have an option than to withdraw our services.”

The strike took place at a time when the government was under attack for establishing new universities while existing ones atrophy from inadequate funding. In the last three years the government of President Goodluck Jonathan, a former university lecturer, has established nine new universities. It has also disbursed $83.7m as varsity “take-off” funds, used by new universities for capital projects and recurrent expenditure. One of the new universities is located in Otuoke, the president’s hometown in the backwaters of Nigeria’s oil-rich but impoverished Niger Delta region.

Critics say the decision to establish new public universities, despite the poor state of current ones, is driven by politics. Mr Jonathan disagrees. At the March convocation of the Ahmadu Bello University in northern Nigeria, he explained the rationale behind the establishment of the new universities.

“The carrying capacity of our universities is still relatively low,” Mr Jonathan said. “It is estimated that the annual number of candidates seeking admission through the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME) for the last couple of years has been hovering around 1.5m while the absorption capacity of our universities is barely a quarter of that figure. When mega universities are established along with the current ones, we believe we will address the crisis of access in the medium term.”

However, the ASUU has argued that adequate funding, not access, is what is required. Indeed, some of Mr Jonathan’s erstwhile colleagues in academia blame him for doing less than expected in this area. Douglas Anaele, lecturer in philosophy at the University of Lagos, is one of them. “For me, President Goodluck Jonathan is a great disappointment to his former colleagues, considering the fact that as a former lecturer, he should have invested heavily and wisely in the educational sector,” he wrote in a recent opinion piece.

“When military dictators were in power, they put a lot of money into defence because that is their primary constituency. There is no good reason why a former academic should not give preferential treatment to the education sector, because well- educated human capital is the most important factor in national development.”

In response to such criticism, the Jonathan administration allocated $2.6 billion, or about 8% of the 2013 national budget ($32 billion), to education. Although the allocation was greater than the 2012 provision of $2.4 billion, the lecturers’ union expressed disappointment, saying that it was not enough.

“Even in the African frontier, you will see that an African country like Ghana is investing not less than 30% of its annual budget on education,” Mr Fagge said. “South Africa has been investing over 30% in education. In the last 10 to 15 years, Nigeria has never invested up to 10% of its annual budget in education.” (South Africa spends about 20% of its budget on education.)

A 2011 paper, “Collapse of Nigeria’s Education Sector: A Call for a Marshall Plan”, by the chairman of Nigeria’s Senate Committee on Education, Senator Uche Chukwumerije, backs Mr Fagge’s claim.

The paper reveals that the education sector’s share of Nigeria’s national budget ranged between 8.8% in 2006 and 7.9% in 2011.

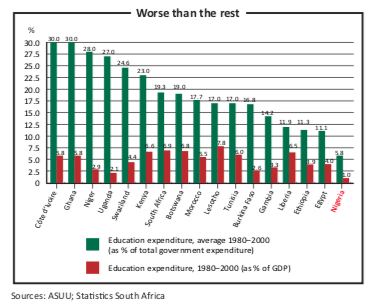

Among leading African countries, Nigeria’s budget has allocated the least to education in the two decades 1980–2000, according to the paper. Africa’s biggest economy, South Africa, expended an average of 19.3% of its annual budget on education during this 20-year period, while Egypt committed 11.1% on average and Kenya 23%.

Nigeria, it says, fared poorly even when compared to its smaller and less well- endowed West African neighbours. Its annual average budgetary expenditure during the two decades was 5.8%, whereas Niger spent 28%; Côte d’Ivoire 30%; Burkina Faso 16.8%; Liberia 11.9%; Gambia 14.2%; and Ghana 30%.

This underfunding has taken a huge toll on Nige- ria’s public universities. The ASUU and the government set up a committee in 2012 to identify the challenges and needs of all public universities. The committee visited 27 federal and 34 state universities, or 71 of the country’s 78 institutions of higher learning. Its comprehensive report confirmed that the Nigerian tertiary education system is on life support.

About 1.25m students are enrolled in Nigerian public universities, according to the report. Of these, 85% are undergraduates, 5% are sub-degree or certificate programme students, 5% are master’s students, 3% are in other postgraduate programmes and 2% are PhD candidates.

More importantly, most of the public universities are seriously understaffed, have more part-time lecturers than full-time ones, are plagued with underqualified academics and hobbled by poor infrastructure, the report says. “Classes are held in improvised open-air sports pavilions and old cafeterias, and even uncompleted buildings are used for lectures. In some cases, workshops are conducted under corrugated sheds or trees. Internet is non-existent, epileptic or slow…and library resources are outdated and manual.”

Disenchanted with the quality of service in the public universities, Nigeria’s emerging middle class has been placing its children in private universities owned by religious and business groups. First established in the late 1990s, their number has now grown to 50.

Others with greater means send their offspring to universities outside Nigeria. Last year a leading Nigerian education NGO, Exam Ethics International, said that Nigerians annually spend over 1.5 trillion naira ($9.3 billion) to educate their children in foreign universities. According to the group, Nigerian students studying in Ghana spend about $992m in that country, while those in the United Kingdom pump $496m into the British economy.

But in a country where over 62.6% of the citizens live below the poverty line of $1 a day, according to the World Bank, the high fees charged by private and foreign universities are a barrier to the majority of students who want a university education. For these teeming thousands, public universities remain the only route to tertiary education.