Nigeria: film and politics

Africa’s largest cultural industry gives voice to upwardly mobile strivers

Want a feel-good story about an African middle class with a Hollywood ending? It is set in Nigeria, the continent’s biggest country by population, brashest by reputation and ballsiest by self-conception. Outside its borders, Nigeria is defined by Boko Haram hashtag campaigns, imploding mega-churches and the occasional piece about political dysfunction. But as an entity (“country” does not quite fit the description), led by the unloved Goodluck Jonathan and his People’s Democratic Party (PDP), it marches toward a general election in 2015, and into a future without certainties or precedents.

Inside, the mise en sceneis somewhat more complicated. No state home to 170m souls can ever be properly united; it will always be a nation of nations. That is certainly the case with Nigeria, which is riven by the tenth parallel, the line of latitude that separates the mostly Muslim north from the largely Christian south. So many of Nigeria’s problems, to say nothing of its indefatigable energy, are generated by this division. But as the energy increases, it becomes more unstable at the core. Regional observers worry that Nigeria will eventually explode into a cluster of Balkanised mini-states.

That is the big picture. Nigeria is also home to thousands—millions—of small pictures, the little stories so many African countries have never been able to tell. In Lagos, the continent’s largest megacity, we find some of Africa’s more vital and powerful cultural companies, each an indication that within the tumult there are those willing to create, pay for, and consume stories. The most famous of the cultural industries is Nollywood, the catch-all term for the Nigerian video-film phenomenon that gives voice to upwardly mobile strivers.

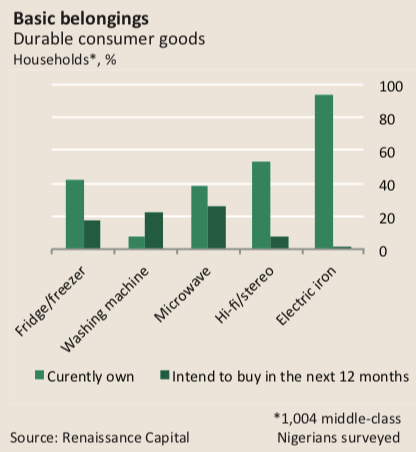

Over 11% of Nigerian households, representing almost 4.1m homes, are now middle class, according to a Standard Bank research paper released in June: a 600% increase since 2000. This cohort found its shape in a 2011 survey by Renaissance Capital, the Russian investment bank.The studyfound that Nigeria’s upwardly mobile, those earning between $480 and $645 a month, were well educated and gainfully employed. While 92% had earned a post-secondary education and 38% ran their own businesses, they were still desperately short of the trappings of middle-class life—just 0.8% of households had two cars, only 42% owned fridge/freezers, and a scant 8% owned washing machines. Nonetheless, according to Standard Bank: “Nigeria towers.”

In the same way that television developed in the 1950s alongside America’s bulging middle class, simultaneously defining and refracting its aspirations, in the mid-1990s—when Africa and a local consumer class began rising—the continent’s storytellers found a forum. The South African media conglomerate Naspers promulgated the idea of a pan-African satellite television empire, now a billion-dollar business beaming signals to every corner of the continent. While over the years Johannesburg and Cape Town—to say nothing of the English Premier League—have provided much of the content for DStv and other Naspers venues, it would not have become a fully realised pan-African project had Nollywood not stepped into the breach.

Or, rather, had Naspers not gone looking for content in Nigeria. Nollywood, legend has it, was born in 1992, during the rule of Sani Abacha’s brutal military junta. Lagosians were largely housebound due to the violence outside their doors, and the country’s once-proud indigenous 35mm film culture reduced to a pale flicker. Social circumstances and technology conspired to create a revolution.

Anelectronic goods salesman named Kenneth Nnebue was sitting on a large consignment of videotapes for which he had no use. Versions of the tale have him either coming up with the idea—or else caving in to the badgering of self-professed “Mr Nollywood” and impresario Okechukwu Ogunjiofor. The idea was togather the big acting names of the day and shoot a tale of a man who gets sucked into a nightmarish money ritual, in which sacrificing loved ones leads to untold riches.

While the moribund National Television Authority, locked in a dispute with talent over payment, programmed a slew of Mexican telenovelas (soap operas), Mr Nnebue’s “Living in Bondage” became an unprecedented smash hit on videotape. “To an extraordinary degree,” wrote the film scholar Jonathan Haynes, “‘Living in Bondage’, the film that started the Nigerian video boom, contains the seeds of almost everything that followed.” After this early example of Nigerian video, sections of Lagos that once sold video players and blank videotapes, most notably Nnamdi Azikiwe Street and Ereko Lane in Idumota, became outdoor film markets and part of a boom as loud, if not as deadly, as oil.

As the industry evolved the bankrolling took shape. Much of the financing came from eastern-based “marketers”—more properly, distributors. This endowed Nollywood with both its unmatchable vitality and its potentially fatal flaw: salesmen doubled as producers churning out as many films as possible as quickly as they could, with little thought to the filmmaking craft, and none at all to the art. Technicians were drawn largely from the Niger Delta region, and writers and directors, at least initially, from TV serials and the Yoruba theatre tradition of south-western Nigeria. By the turn of the century, after Sani Abacha’s death and the re-introduction of democracy in 1999, Nigeria was one of the planet’s more prolific centres of film production.

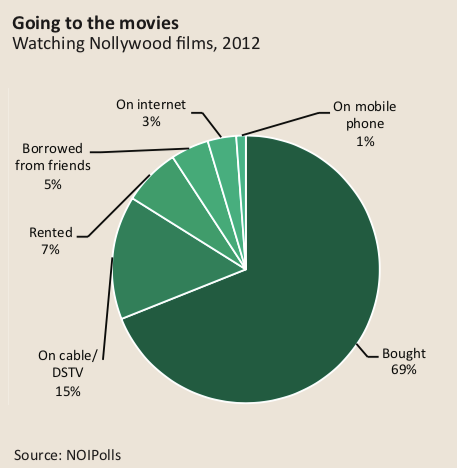

The video-film industry minted many new middle-class aspirants. It also filtered their lives and dreams through stories that seemed authentically Nigerian. A 2008 survey by the Nigerian film board found that as many as 1,711 films had been produced. While the industry has levelled off somewhat since, the best estimate is that in 2011 filmmakers were shooting 50 features a week, providing employment for 300,000, generating anywhere between $286m and $600m a year in revenue, depending on the study. The average Nollywood movie costs between $25,000 and $75,000 to produce, takes as little as a week to shoot, and after a speedy turnaround sells 20,000 to 200,000 units at $1.50 a pop.

Naspers bought entire libraries from marketers to programme Africa Magic and other channels. The Nigerian middle class was splashed across television screens in Ghana, Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania and further afield, most of whose viewers were already in the know thanks to those roving video tapes.

Over the years, the industry has evolved—some might argue nowhere near enough. There is now a burgeoning indie wave, which corresponds with American independent cinema, as well as a premium New Nollywood, best evinced by the recent adaptation of Nigerian-born writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Half of a Yellow Sun”, starring Hollywood luminaries Chiwetel Ejiofor and Thandi Newton. But it is where these films are consumed that is just as important. DStv still programmes them on Africa Magic and other channels, and they are still sold across the continent as digital video recordings. But in Nigeria, a cinema culture has re-emerged, tied to the growth of mega-malls.

Filmmaking technicians have deep ties to the Niger Delta. In 2013 Governor Seriake Dickson, of oil-soaked Bayelsa State, made big commitments to an industry he sees as providing an alternative to the violence and shame of oil. The governor’s masterstroke was the announcement of a film industry trust fund with an initial disbursement of about $16m, which would function in tandem with a pledge of just under $190m from the federal government in Abuja. In addition to these initiatives, Mr Dickson promised to build an underwater “imaging facility” and a film school for the training of technicians within a larger Bayelsa Film and Arts City.

To insiders, the subtext was as obvious as a Nollywood plotline. With Niger Delta native and former governor of Bayelsa, Goodluck Jonathan, serving as president, Nigeria’s powerbase ran through the region like a steel spine. Just as Hollywood players, almost without exception, are associated with the Democratic Party in the United States, so too are Mr Jonathan and Mr Dickson—the latter considered to be within the president’s inner circle—trying to consummate a marriage between the PDP’s Delta element and Nigeria’s film cabal.

No living Nigerian embodies this relationship with greater alacrity than Kate Henshaw. In 1992, Ms Henshaw was studying medical microbiology at the University of Calabar in south-eastern Nigeria when she auditioned for a modeling contract. Days later, she became the African face for Shield deodorant. By the mid-1990s, she was making about $150per film and amassing dozens of credits, including an African Movie Academy Award in 2008. But as the years wore on, Ms Henshaw’s outlook changed. “I try not to do too many films these days,” she said. “I want to do quality work—after 20 years, you have to be picky.” Her sights turned to radio, reality TV, music, and to politics. In April 2014 she hitched her wagon to the PDP, and will run for parliament in 2015 as a celebrity candidate fighting for the middle class and their values: better growth, more stability, less crime, zero corruption.

No longer just hastily made movies played in ramshackle video clubs, Nollywood has raised a stable of stars that are now coming into power. Many, like Ms Henshaw, will help to influence not just commercial tastes, but political leanings. As Africa’s largest cultural industry matures, it will increasingly become not just a vector for middle-class voices but something more—a portal into Nigeria’s future, driven by a political class who grew up in front of the camera. Africa’s biggest country by population and economy is defining trends that may last for generations: actors who once played at being middle class in the movies, now playing at being president in State House. It could happen. In Nollywood, anything is possible.