Tension simmers along Kenya’s pristine beaches near Mombasa, the country’s second- largest city and a major tourist destination. This Indian Ocean resort is the site of recent terrorist bombings and rioting.

by Clar Ni Chonghaile

Along Kenya’s beaches, coconuts thump dully on white sand sloping to turquoise waters and reefs filledwith starfish. But behind this paradise lies another picture—one of poverty, crippling unemployment, paltry public services and a discontent that is fuelling fears of violence ahead of next March’s presidential elections.

The Mombasa Republican Council (MRC), a once-outlawed group that is now facing a new crackdown, wants Kenya’s coastal region to secede. Claiming to have 2m adherents, it charges the central government in Nairobi with neglect and historical betrayal.

Omar Faraj, 44, is the MRC’s assistant co-ordinator. While dodging minibuses and three-wheeled tuk-tuk taxis on a busy street in this port city, he gestures at the dirty plastic bags, bits of food and cartons piled carelessly behind rickety stalls. “This is Kenya’s second city,” Mr Faraj says. “You see how it is. And they wonder why the MRC came about.”

Mr Faraj’s anger reflects the frustrations of many coastal people, especially the youth, who feel disenfranchised and claim that wabara (outsiders in Kiswahili) have stolen their land and plundered their resources.

Although tourism and trade at Mombasa’s port bring in millions of dollars each year, many locals say the only beneficiaries are people from other parts of Kenya and not members of the local indigenous tribes, the Digo, Swahili and Giriama. Kenya earned $1.1 billion from tourism in 2011.

Rioting broke out on August 27th 2012 in Mombasa after unidentified assailants gunned down radical Muslim cleric Aboud Rogo in broad daylight. The Kenyan and United States governments had accused Mr Rogo of supporting the Islamist militants of the Shabab in Somalia.

The MRC said it was not involved in the riots, which lasted three days. It counts both Christians and Muslims among its supporters. The street protests, however, underlined the multiple tensions that have swelled the group’s ranks as it campaigns on the slogan Pwani si Kenya (the coast is not Kenya).

Kenya’s coast boasts a long heritage distinct from the interior. Records of foreign trade date to the 8th century. By the 10th century, Arab and Persian merchants began establishing settlements. As trade hubs such as Mombasa grew, so too did Arab migration to the coast. An Islamic culture and the Swahili language emerged along the coast from intermarriage between Arab settlers and indigenous Africans. Vasco da Gama’s visit in 1498 sparked Portuguese interest. For the next 200 years, the Portuguese competed with Arab sultanates for control. Omani Arabs eventually emerged triumphant, only to come under British rule in the 19th century.

While Kenya’s interior was a British colony, the coast was a British protectorate. (A protectorate is an independent country under the control of a protector while a coloniser controls a colony.) Upon independence in 1963, the coast was integrated into Kenya by an accord between the Sultan of Zanzibar and Jomo Kenyatta, independence leader and later Kenya’s first president. The MRC disputes the terms of this agreement and says the coast was only leased to Kenya for 50 years, until 2013.

The MRC says it has documents that prove its claim but the government and some historians say the documents are fakes.

Today the coast’s cosmopolitan history is evident in the mosques and wooden balconies in Mombasa’s Old Town, still perfumed by the spices once traded here. Hawkers on narrow streets sell figs, dates and Muslim caps or kofias. Women in dark buibuis (shawls) rub shoulders with girls in mini-skirts and look-at-me shades.

“We are demanding secession because of the oppression by the government of Kenya,” said Randu Nzai Ruwa, the MRC’s secretary-general. Last August while sitting in a scruffy room above a noisy street in downtown Mombasa, he blamed Nairobi for “neglecting the region”.

Statistics seem to agree. In a November 2011 report on the MRC, researcher Paul Goldsmith wrote that three of the six coastal counties—Tana River, Kwale, Kilifi— and the city of Malindi rank among the 15 poorest districts in Kenya.

“Landlessness and social exclusion form a volatile matrix in a region where outsiders dominate economically,” he wrote.

Mr Ruwa traced the inequity to land grabbing following independence and blamed Mr Kenyatta. Kenya’s colonial administration had declared all land to be crown land. White settlers took large tracts, particularly in the Central and Rift Valley provinces.

In the early 1960s, Mr Kenyatta’s administration used British government and World Bank loans to buy back the land. Here, the president resettled people who were previously displaced, or fighters from the uprising against Britain. Mr Kenyatta favoured his Kikuyu tribe in these allocations. When Mr Kenyatta died in 1978, Daniel arap Moi came to power and continued the practice of using land as a political resource.

“The acquisition of beachfront property required presidential assent,” Mr Goldsmith wrote. “Settlement schemes on the coast provided a vent for landless peasants from upcountry and the upcountry settler base encouraged the migration of family members and kin. Wealthy businessmen from the highlands came in search of other properties to buy in their wake.

“The coastal communities’ fears over losing control of land and key economic resources in 1963 were realised over the next five decades,” he added. “This has led to a crisis of state legitimacy.“

When outsiders develop the land today, they bring in other wabara to do the work, Mr Ruwa said. The coast’s indigenous tribes do not benefit.

“Everything comes from Nairobi,” Mr Ruwa added. “When a tourist comes, they will say this area has been developed because there are some big houses and good shops. But the local person does not enjoy the development. The people from upcountry are given priority. We have been made slaves in our lands.”

Land disputes are common across Kenya. They are particularly emotive ahead of elections. During the violence that exploded after the disputed results in the 2007 presidential ballot, thousands of people were driven from their homes as tribe turned on tribe, sometimes venting anger about perceived land injustices. Around 1,200 people were killed.

There had been hope that the creation of a national land commission, as decreed in a new constitution adopted in 2010, would help resolve some of these outstanding issues and prevent a repeat of the 2007–08 chaos.

The commission, which has yet to be constituted, has broad powers to manage public land, recommend a

national land policy and advise the government on a comprehensive programme for registering titles throughout Kenya. It also has a mandate to resolve historical land injustices.

Robert Ndege, a political risk consultant at Africapractice in Nairobi, says that resolving disputes will depend on the commission’s effectiveness and whether politicians, some of whom have large land interests, will allow it to do its work. Addressing property grievances “will take a long time and will need to be handled delicately so that it does not inflame tensions”, he said.

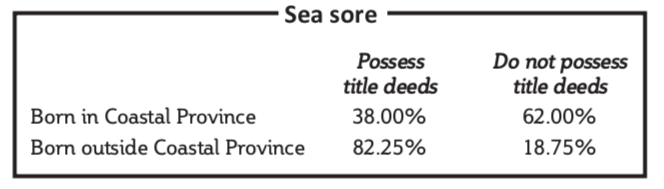

But Mr Ruwa fears coastal people will still be left out. “Most of our people don’t have title deeds … so that means that they are not recognised by the government as owning shambas (small farms),” he said.

The only answer is secession, Mr Ruwa said. Most analysts agree this will never happen. The MRC’s real significance, however, may lie in the effect it could have on next March’s vote, the first election since 2007.

The MRC wants its supporters to boycott the poll, a call that could fan conflict be- tween those who agree and those who want to vote in a region seen as an election hotspot. The government banned the MRC in 2010, accusing it of having links to violent organisations. But after no evidence was found to justify this charge, a court lifted the interdiction in late July 2012.

However, a spate of violent incidents in recent months has led to a new crack- down on the movement. On October 19th, a court in Mombasa declared the group illegal again. Several leaders, including Mr Ruwa, have since been arrested. President Mwai Kibaki has said his government will take decisive action against those who “issued threats of seccession or those who threaten our security”.

In his report, Mr Goldsmith found no evidence of an official armed wing to the MRC.

In August Mr Ruwa denied allegations that the MRC has links to militant groups, such as the Shabab. The real danger, he said, lay in its young supporters’ growing frustration.

On October 20th men with machetes attacked a police station in Kaloleni, west of Mombasa but were thwarted by police. The attackers then raided a police camp further away, wounding a police officer and seizing a rifle, according to a local government official. Again, police blamed the MRC.

Suleiman Shahbal, a coastal businessman who is running for governor of Mombasa, acknowledges the validity of the MRC’s fundamental grievances. He opposes an election boycott, however, saying coastal people finally have a chance to take control under a new system of devolution that will grant more power to county authorities.

“A lot of the people at the coast feel that the electoral process has failed us,” he said. “We have major issues with unemployment. People feel we are being marginalised, and land issues, which should have been resolved 50 years ago, are still unresolved. That has led to the frustration that you are now seeing epitomised by [the] MRC.”

Mr Ndege said authorities should reach out to the MRC. “There needs to be a more subtle approach,” he said. “There needs to be engagement.” But as the October events show, the government has opted for a tough approach.

As the interview ended, Mr Ruwa insisted on playing a song stored on his cell phone. Mr Faraj and the other MRC officials in the room seemed almost childishly excited.

Tinny voices and foot-tapping music filled the air. “You have taken all the resources to Nairobi, and the coast people are left with nothing. We want our country,” Mr Ruwa translated. Then the catchy chorus rang out: “Pwani si Kenya.”