Saving Africa’s rhinos

As anti-poaching efforts fail, legalising the trade of rhino horn may be a solution

The history of rhino conservation was, until recently, one of marked (and market) success. Fewer than 1,000 southern white rhinos existed in Africa in 1960.

The rise of private game farms started in that decade, and by 1991 there were nearly 6,000 specimens, mostly in South Africa. Traffic International, the wildlife trade-monitoring network, declared in a 1992 report that the animals were “well conserved”.

South Africa’s 1991 Theft of Game Act changed the legal status of game. For the first time, wildlife ownership was endorsed and regulated, and game could be bought and sold. This was followed in 1994 by an important reclassification of the southern white rhino under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

The treaty’s Appendix I prohibited all trade in the species or its products, but Appendix II—under which white rhinos now fell—allowed limited trade and trophy hunting, subject to a permit system. As the auction value of animals soared, so did their population.

By 2010, more than 20,000 southern white rhinos were counted, 96% of which roamed South Africa’s game farms and national parks, according to “Saving African Rhinos”, a 2011 study by independent South African environmental economist Michael ‘t Sas-Rolfes for the US based Property and Environment Research Center.

Black rhino for many years followed an opposite trajectory. In 1960, more than 100,000 black rhinos of several subspecies remained in Africa, according to Mr ‘t Sas-Rolfes. Because they mostly roamed countries that lacked adequate conservation programmes and private game farms, rampant poaching reduced their population to a mere 2,500 by the early 1990s.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature, which administers the CITES treaty, declared the western black rhino extinct in 2011. The same legislative changes in South Africa that turned the tide for the white rhino population to recover also worked for the remaining black rhino subspecies.

The population has since recovered to around 5,500, and South Africa became their most important home, according to the ‘t Sas-Rolfes study. But five years ago, the peaceful idyll was shattered. Rhino horn had always been traded for ornamental and medicinal purposes to markets in Yemen, Vietnam and China.

But the liberalisation of trade in live rhinos did not extend to their horn and the artificially restricted supply prompted its price to rise.

Today rhino horn is valued higher by weight than gold, at a black-market price of $65,000/kg. Fundisile Mketeni, deputy director for biodiversity at South Africa’s Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA), confirmed this price at a July 2013 press conference.

Tom Milliken, director of TRAFFIC’s East and Southern Africa programme, told a documentary filmmaker that the spike starting in 2008 was driven by a new rumour of rhino horn as a cancer cure in Vietnam, where rhino horn has long been viewed as a “miracle medicine”.

Mr ‘t Sas-Rolfes, however, disputes this: “My own view is that there is nothing especially ‘new’ or remarkable about the recent market activity,” he said in a February 2012 market analysis, which he published privately as an independent consultant.

“All that has happened is a realignment of market supply and demand factors” including Vietnam’s rapid economic growth, he added. As is the case with many other goods that are heavily taxed or outlawed— including oil, tobacco, alcohol, drugs and weapons—demand barely dropped in response to a higher price. Economists describe this phenomenon as “price inelasticity”.

Mr ‘t Sas-Rolfes has studied the economics of endangered species for almost a quarter of a century. “The problem with price-inelastic demand is that when you restrict supply, the illegal trade actually becomes more profitable, not less,” he said. “This…attracts serious professional criminals.” Such syndicates began to target South Africa’s rhino population in 2008.

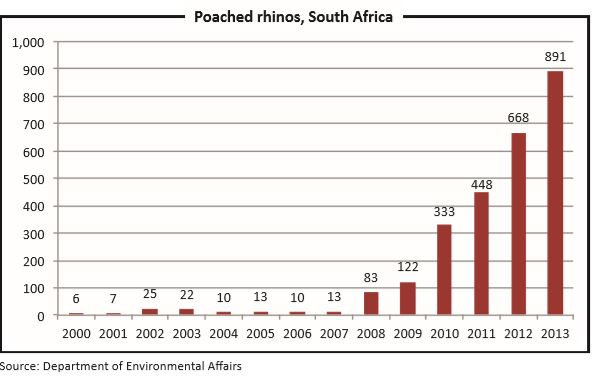

For most of the previous decade, only a dozen or so animals were lost to poachers in any year. In contrast, 83 animals were killed for their horn in 2008, according to DEA data.

Since then, the poaching rate has climbed alarmingly, by about 60% per year, according to this author’s calculations based on the DEA statistics. As of November 27th 2013, according to the latest DEA statistics available, 891 animals had been slaughtered since the beginning of the year.

John Hume, a game farm owner whose 900 head of rhino make him the largest private rhino owner in South Africa, actively campaigns for the legalisation of the trade in rhino horn.

He expects the number of animals lost to poachers to hit 1,000 by the end of 2013 and says the country will lose 2,000 rhinos per year by 2016 if the trend continues. The DEA’s poaching statistics confirm this prediction.

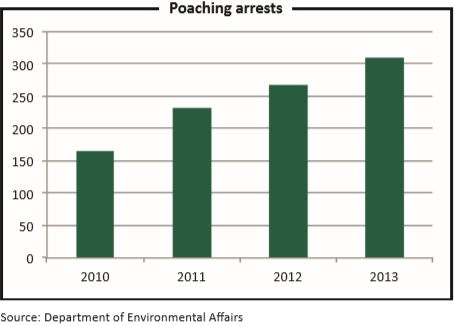

Despite expensive government and private initiatives to combat poaching, the onslaught persists. In 2013, only 310 poachers were arrested, and the annual growth rate in arrests since 2010 is only 20%, according to DEA statistics.

The illegal supply to the black market remains well clear of enforcement efforts. In Mr Hume’s view, there simply is no economic way to stay ahead of poachers when an animal is worth only its auction value to a game farmer, but is worth several times more to sophisticated and heavily-armed poaching syndicates.

The black marketeers easily recruit cannon fodder from poor local communities who have no economic stake in the animals and are willing to take big risks for relatively little reward.

The crisis has led the South African government to consider approaching CITES with a proposal to legalise the trade in rhino horn. In stockpiles alone, the country possesses some R10 billion ($1 billion) worth of horn, according to Mr Mketeni, which would dramatically alter the balance of power against poaching syndicates.

The hope is that legal trade will increase the value of game farm stock, enabling farmers to invest more into security. Legal trade may also reduce the price of rhino horn, making it less attractive to black-market syndicates.

The success of any proposal at the next CITES meeting, to be held in South Africa in 2016, is far from assured. It would have to gain the support of two-thirds of member countries before being adopted.

CITES is infamous for its political horse-trading. In 2010, Tanzania and Zambia proposed lifting a moratorium on legal trade in elephant products in the hope that this would undermine the poaching-dependent black market in ivory.

A group of 23 central and east African countries did not agree with their proposal. They argued that it would further harm African elephant populations, which were already in decline.

Reuters unearthed a leaked letter describing how these countries made their support for a European Union proposal to ban the trade in Atlantic bluefin tuna conditional on the EU states voting against lifting the ivory trade moratorium. In the end, neither proposal was carried.

In addition, powerful environmental groups, including the World Wide Fund for Nature and the International Fund for Animal Welfare, are ranged against any rhino trade proposal, arguing that a legal trade will stimulate demand without deterring poachers. Proponents of legal trade retort that this is exactly what the ban has been doing.

“The data suggests that banning of legal, open trade in rhino horn has not resulted in reduced demand for the horn, and has not helped save the rhino from imminent extinction,” Johnny de Lange, chairman of the Portfolio Committee on Water and Environmental Affairs, told South Africa’s parliament. “Escalation in the slaughter of rhino is proof of this.”

Opponents of legal rhino horn trade also point to the failure of a limited legal trade in ivory to stem the elephant poaching tide.

The cases are difficult to compare: rhino horn is a renewable resource that can be harvested from live animals while ivory is not. Ivory has largely been sold in isolated auctions and not through ongoing trade supported by breeding farms. In addition, elephant ranching is significantly harder than farming rhinos, according to Mr Hume.

Kenya has indicated that it would not oppose South Africa’s rhino trade proposal to CITES, but insists the country ban the export of hunting trophies for five years. So-called “pseudo-trophy hunting” involving bogus hunters has long been used to get horn out of South Africa.

Rhino horn syndicates recruit hunters as fronts to obtain legitimate licences and then violate the licence condition that prohibits the sale of the valuable horn.

In response, Pelham Jones, chairman of the Private Rhino Owners’ Association, wrote an open letter to CITES member states, published on the association’s website, arguing that Kenya’s plan would devastate South Africa’s private rhino industry.

“The road to hell is unfortunately paved with good intentions and at present we are watching the rhino populations in our country being condemned to extinction because of such misguided and naive good intentions,” he wrote.

In a presentation given to the 16th Conference of the Parties to CITES, held in March 2013 in Bangkok, Mr Jones explained that any reduction in income potential would lead to widespread disinvestment by private rhino owners.

The security costs of protecting rhino from poachers had already risen from R160m ($16 million) a year to R450m ($45 million).

Mr Jones argued farmers would struggle to absorb even higher costs, if incomes were to decline. He also predicted that rhino might be extinct as soon as 2026, which agrees with a simple extrapolation of the DEA’s official population numbers and poaching rate.

Mr Hume believes strategies such as trying to reduce foreign demand through education cannot possibly work in time to save the rhino. Some proposals, such as destroying rhino horn stockpiles, can only increase black-market prices and motivate further poaching.

He agrees with Mr Jones that as security costs continue to rise, game farmers will find rhinos more trouble than they are worth, and many will dispose of their stock instead of breeding them.

The only certainties in the rhino horn debate are stark: the ban on trade is failing to protect the rhino. At the present growth rate of illegal poaching, rhinos will be extinct in just over a decade.