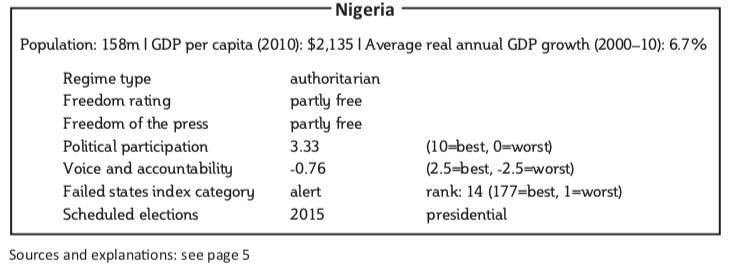

Nigeria’s opposition fails to convert public discontent into victory.

by Adeyeye Joseph

Inside Nigeria’s cacophonous public buses, spontaneous and passionate state-of-the-nation debates are common. Consensus, however, is rare. Of all the views readily expressed, only one always seems to enjoy majority support: the ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP) is more of an albatross than a national asset. This sentiment is as prevalent on the streets as it is in the country’s internet and media watering holes.

“Nigerians would be very glad to kick out the PDP and pave the way for a new government that will take care of their basic needs and move the country forward,” said Lai Mohammed, spokesman for Nigeria’s biggest opposition party, the Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN).

At a recent lecture, Kassim Shettima, a governor for the opposition All Nigeria People’s Party (ANPP), described the PDP’s decade-long hold on power as full of “lethal hunger, brutal insecurity, fatal unemployment, crippled education, substandard healthcare … ”.

Figures from the Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) bear out his claims. The government-funded bureau’s annual report for 2010 is the latest in a series of documents that show the majority of Nigerians are in dire straits despite strong economic growth, which averaged 6.7% between 2000 and 2010 according to the World Bank. The NBS states that in 2010, 60.9% of the country’s estimated 158m people lived in “absolute poverty” compared to 54.7% in 2004. The World Bank defines “absolute poverty” as living on $1.25 or less a day at 2005 prices.

This increase in poverty is mirrored by the NBS’s 2011 unemployment report, which states that the national unemployment rate in Nigeria had increased from 19.7% in 2009 and 21.1% in 2010 to 23.7% in 2011.

“It remains a paradox … that despite the fact that the Nigerian economy is growing, the proportion of Nigerians living in poverty is increasing every year,” said Yemi Kale, director-general of the NBS, at the presentation of the report in early 2012.

These statistics have long served as handy talking points for opposition parties pointing to Nigeria’s obvious lack of progress under the PDP and Goodluck Jonathan, the president. They are used as a good reason for the party to be voted out of power.

But in all of the four elections held since the advent of Nigeria’s Fourth Republic in 1999, the opposition has consistently failed to parlay public discontent into victory over the PDP in presidential elections.

History and image partly explain this conundrum. The PDP’s roots are deeply embedded in Nigeria’s complex civil-military power structure, which predates its formation in 1998. Within the ranks of the ruling party are senior conservative politicians and ex-military generals who have ruled Nigeria, on and off, for over 50 years. Their influence and wealth help the party to sustain a countrywide network of grassroots party bosses, corrupt policemen and toughs responsible for the party’s victories in successive elections.

Currently the PDP is in power in 22 of Nigeria’s 36 states. It also controls Abuja, the federal capital, whose head is appointed by the ruling party. In the country’s bicameral legislature it has 71 of 109 Senators and 202 of the 352 seats in the House of Representatives.

Beyond the PDP, the other hurdle that the opposition has struggled to scale is its negative public image. The common notion is that the leading opposition parties are only a shade better than the much-vilified PDP.

Dele Momodu, popular columnist and National Conscience Party (NCP) presidential candidate in the 2007 general elections, elaborated on this popular view in a recent column on the Nigerian opposition.

“The tragedy of the opposition in Nigeria presently is that there is no difference in party ideology and structure between the PDP and the so-called opposition,” he writes. “By all intents and purposes they are the same and therefore considered as really not having much to offer.”

Pat Utomi, public intellectual and senior lecturer at the Lagos Business School, posits that Nigerian political parties are no more than a “combination of electoral machines, cults of personality and private estates”.

The Independent National Electoral Commission authorised an external auditors report on all the 56 registered political parties in Nigeria early in 2012. The report concluded that parties neither maintain proper accounts nor obey their own constitutions. The parties, the report appears to say, are run like sole proprietorships.

Party bosses whose images loom larger than their parties are the leaders of Nigeria’s two leading opposition parties, the ACN and the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC).

Bola Tinubu, a veteran of Nigeria’s anti-military battles in the 1990s, leads the ACN, which controls six states. A former two-term governor of Lagos, Mr Tinubu earned the admiration of many Nigerians when, as the sole opposition governor in western Nigeria, he won a lengthy revenue court battle against the PDP-controlled federal government.

Muhammadu Buhari, a former military head of state and perennial presidential candidate, is the leader of the CPC. Mr Buhari and his party have a huge, almost fanatical following in the north of the country. The retired general has contested presidential elections thrice, losing each time, but still holds on to his almost cult-like following in the north.

Analysts say a successful alliance between the two parties, warts and all, is the opposition’s only chance of defeating the PDP presidential candidate in 2015. Despite their failings, the ACN and CPC have rattled the PDP behemoth at state, legislative and local government elections.

In the 2011 legislative elections, the opposition parties made inroads into the ruling party’s substantial majority in Nigeria’s legislature. The ACN took 66 seats in the House of Representatives in 2011, just over double the 32 seats won in 2007. In the Senate, the ACN won 18 seats in 2011, a substantial increase from six seats in 2007.

The question is: can the Nigerian opposition replicate its successes in regional elections at the national level? The opposition says “yes”. In May this year, the CPC held exploratory talks with other parties. Afterwards, one of the party spokesmen, Rotimi Fashakin, said the opposition parties would come up with a “rainbow coalition” that will defeat the PDP in the 2015 presidential poll. He added that “any party is a potential partner” save the PDP.

But the devil lies in the history. In 2003, 2007 and 2011, opposition alliances either floundered or failed to meet expectations. Ego clashes, poor coordination and squabbling over the selection of candidates unravelled the alliance.

The failure of the 2011 ACN/CPC alliance is instructive. The alliance, heralded with much fanfare, fell apart a few days before the poll after both parties failed to agree on a vice-presidential candidate.

While opposition leaders acknowledge this problematic past, they insist that enough lessons have been learnt to forestall a repeat of history. A former information minister and stalwart of the CPC, Prince Tony Momoh, is one such optimist: “In the past, [bad] timing contributed immensely to the failure of the merger plans. Now, we have enough time and better understanding of the challenges facing this country,” he said. “Fortunately, this election is in 2015 and that’s still some time away. We have sufficient time to perfect our act.”

Is Mr Momoh’s optimism misplaced? Columnist Momodu hopes not. “Nigeria is haemorrhaging to death,” he says, “and the opposition really needs to sit up.”