India’s diaspora in Africa

From adventurous seafaring traders to forced labourers to billionaire businessmen

Families of Indian origin control some of Africa’s largest companies and three of the continent’s richest men are Indo-African.

The Dewji family owns Mohammed Enterprises Tanzania, with interests in manufacturing, distribution, trading, haulage, storage and real estate. Annual revenues are $1.3 billion and the firm employs a workforce of over 20,000 people, according to CE Mohamed Dewji, who runs the family business.

In Ghana, the diversified Mohinani Group has created 3,000 jobs in its multi- sector operations that range from packaging and plastics to trade and distribution of chemicals.

In Uganda, Ashish Thakkar began his entrepreneurial journey in 1997 as a high school student selling computers to his schoolmates and friends. Today his operation has grown into a diversified conglomerate with approximately $1 billion in revenues, according to Mr Thakkar, a 32-year-old billionaire now residing in Dubai.

In addition to these prosperous families, three men of Indian origin—Vimal Shah, Sudhir Ruparelia and Naushad Merali—are among the 50 richest people in Africa in 2013, according to Forbes magazine.

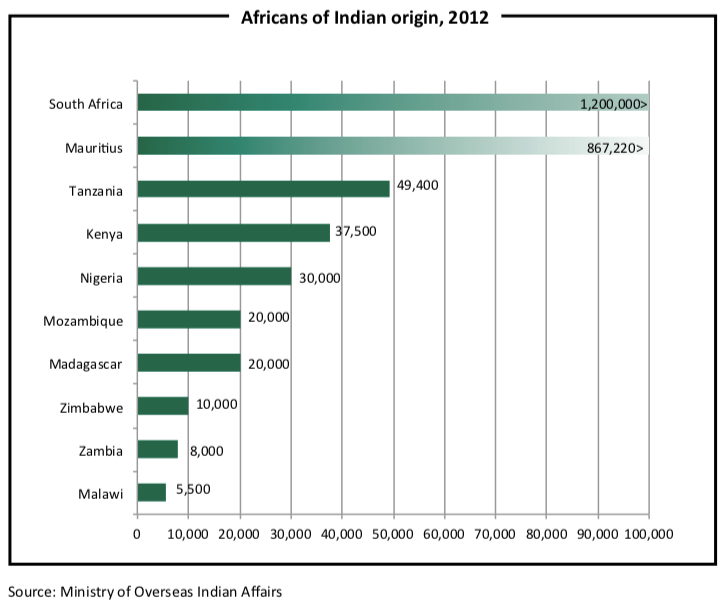

They are among the estimated 2.3m people of Indian origin living in Africa, according to India’s Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs. The vast majority live in South Africa and Mauritius, but many sizable Indian diaspora communities are thriving across the continent’s southern, eastern and western regions.

Mr Shah, 18th on the Forbes list, is chief executive of Kenya-based Bidco Oil Refineries, the largest manufacturer of edible oils in east and central Africa. Indian businessmen such as Mr Shah have been trading in Africa since the 16th century. For 300 years, these businessmen favoured the east African coast because of its proximity to India. They traded pepper and textiles in exchange for ivory, animal pelts, tortoise shells and gold, according to Zoe Marsh and G.W. Kingsnorth’s “A History of East Africa”.

Labour, not trade, brought the Indians to settle permanently in east Africa. Following the abolition of slavery by the British in 1833, the colonies urgently needed manpower. To meet this demand, the British established an organised system of temporary labour migration from the Indian sub-continent. The British colonial powers forced Indian labourers to work on colonial infrastructure projects such as the Uganda railway, which linked the interiors of Uganda and Kenya with the Indian Ocean and was completed in 1901.

The British colony of Natal in southern Africa also needed cheap workers, especially on its sugar plantations. So it struck a deal with Britain and the British Indian government to import indentured labourers from India. This suited India, too, because many peasants in India were unemployed.

Between 1860 and 1911 more than 150,000 Indian migrants arrived in Natal as indentured labourers, wrote Rick Halpern, a University of Toronto history professor in a March 2004 article in the Journal of Southern African Studies. Although the majority worked on the sugar cane plantations, many also worked on the railways, dockyards, in the municipal services, in coalmines and in domestic service.

The next wave of Indian immigrants to east Africa arrived in the early to mid-20th century, according to J.S. Mangat in “A History of the Asians in East Africa: 1886-1945”. Unlike their predecessors, they came voluntarily. Many of them, primarily from Mumbai, Gujarat and other western areas of India, were middle-class merchants. Unlike previous Indian traders, they brought their families and first settled permanently in coastal cities such as Kenya’s Lamu and Mombasa. They later moved to Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, Uganda’s Kampala, and Tanzania’s largest city, Dar es Salaam. This second wave were known as “passenger Indians” because they paid their fares to board steamships.

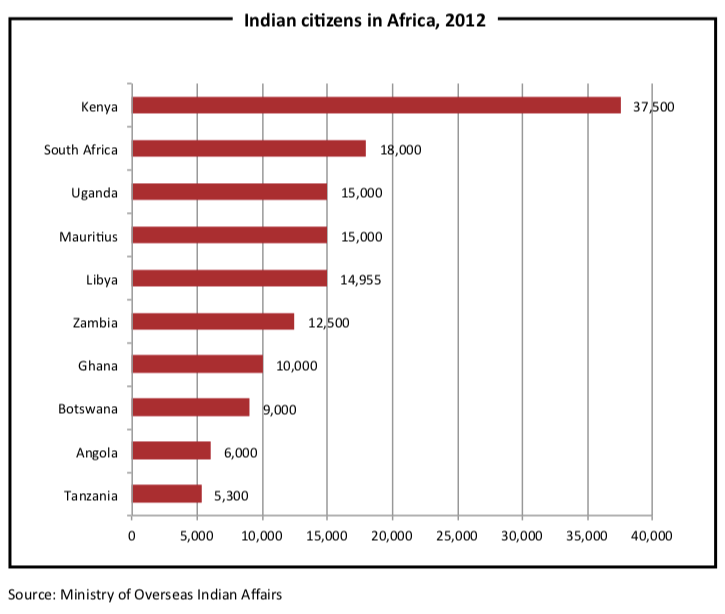

Indians from Gujarat also arrived in Zambia in 1905 in what was then the British territory of North-Eastern Rhodesia. About 20,500 Indian citizens and Afro- Indians currently reside in Zambia, according to India’s overseas ministry. Most work as traders, according to the Indian High Commission.

Indians emigrated to west Africa after mass violence erupted with the dissolution of the British Raj in India in 1947. Sindhis—from India’s north-west—were the first to arrive on Ghana’s shores, initially as traders and shopkeepers. Gradually, in the 1950s and 1960s, a few started manufacturing garments, plastics, textiles and other goods, according to the Indian Association of Ghana. About 10,000 Indian citizens live in Ghana, and about 30,000 Indo-Africans live in Nigeria, according to the overseas Indian affairs ministry.

Their entrepreneurial nature and adventurous approach to business led the Sindhi community to search for new opportunities far from home. From anecdotal discussions with older members of his family, which spans from Lagos, Nigeria to Port Louis, Mauritius, this writer can testify that this was the main driving factor.

In addition to commerce, the Indian community has also made a significant contribution to Africa’s social and political fabric. Mohandas Gandhi began his career in activism in South Africa. During his 21 years there from 1893 to 1914, he developed satyagraha, his hallmark philosophy of nonviolent resistance that led India to achieve independence in 1947.

African independence leaders such as Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere and Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda have stated that Gandhi’s philosophies and achievements inspired them.

Yet despite the myriad successes, the past 60 years have not been plain sailing for Africa’s Indian population. Indian diaspora communities and locals have at various times accused each other of discrimination, especially in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania. In these east African countries, relations between these groups hit their nadir between the late 1960s to the early 1980s over the issues of nationalisation and citizenship.

Uganda’s dictator Idi Amin ordered the expulsion in August 1972 of 80,000 people of Indian and Pakistani heritage and gave them 90 days to leave, according to Elliott P. Skinner in the 1979 “Strangers in African Societies”. In Tanzania and Kenya, Africans perceived Indians as the main reason for the economic malaise in their respective countries. This “Indophobia” fuelled the nationalisation of Asian-owned businesses in the 1970s and 1980s. In Kenya, Asian-owned shops and homes were looted and Asian women were raped in the chaos that followed an unsuccessful coup attempt in 1982, according to news reports.

Reasons for resentment towards Indians in these countries are varied. During the colonial period, Indians occupied a middle position between black and white in the colonial hierarchy. They lived in their own communities and often received more privilege than Africans. Under British rule, for example, Indians in Kenya prospered more than Africans and even won nominal representation on the legislative council.

President Yoweri Museveni’s 1986 election turned the tide for Indians in Uganda. He restituted expropriated property and invited Indians to return to boost the trade and manufacturing that had declined after Mr Amin’s expulsion of Asians, according to Renu Modi, faculty member and former director of the Centre for African Studies at Mumbai University.

Sanjiv Patel is among those who returned. He came back to Uganda from Kenya in 1991. He is now the director of Tomil Agricultural Limited, a diversified family business that trades cotton, coffee, tobacco and other commodities. “I’m a third- generation Ugandan and a returnee,” Mr Patel said in a 2011 article published by India’s The Economic Times. “I consider this my home.”

Like Mr Patel, Indians started returning to east Africa, mostly from the UK, in the early 1990s after trade was liberalised, bringing with them their expertise and investments, according to “They Came to Africa: 200 Years of the Asian Presence in Tanzania”, a book of oral histories compiled by Lois Lobo and published in 2000.

The ghosts of the Amin regime’s expulsion still linger for many of Africa’s older generation of Indians. They worry that they will never be truly accepted in their adoptive countries. The younger generation, however, view themselves as African first and Indian second. They have come to terms with the diaspora’s complex identity politics.

RONAK GOPALDAS is a director at Signal Risk, an exclusively African risk advisory firm. He was previously the head of country risk at Rand Merchant Bank (RMB) for a number of years, where he managed a team who provided the firm with in-depth analysis of economic, political, security and operational dynamics across sub-Saharan Africa. He holds a BCom degree in philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) and a BCom (Hons) from the University of Cape Town (UCT). He also has an MSc in finance (economic policy) through the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London.[