Zimbabwe: sifting for gold

Poor people and reckless mining companies are endangering Zimbabwe’s rivers

Alluvial gold panning is relatively simple, potentially lucrative, and very harmful to the environment. For Zimbabwe’s rivers, this is proving a dangerous combination. With the country’s economy in profound crisis, and poverty and unemployment endemic, thousands of people—mostly young and poor—are panning for gold along the banks of the country’s rivers. About 500,000 at last count, according to a 2010 report by the parastatal Environmental Management Agency (EMA).

Together with larger-scale mining activities, the panning poses a serious threat to the ecosystems of these rivers and to the livelihoods of the communities that depend on them. To mine the alluvial gold that collects in riverbanks, panners dig out soil from the bank and pass it through sifting pans that separate gold from stones and other unwanted material.

They sell it to black-market buyers including jewellers and middlemen, some of whom smuggle the gold out of the country. Such extensive digging causes erosion and siltation, the increased concentration of mud and other sediments in the water.

Siltation has various harmful effects: not only does it destroy the habitats of fish and other forms of aquatic life, it also reduces a river’s water-carrying capacity and can clog dams downstream. Siltation is only one part of the problem. Mercury and cyanide are widely used by the panners to process the gold, explained EMA spokesman Steady Kangata.

When these chemicals, which are highly toxic, are released into the water, they kill or harm a river’s fish and plants and put people at risk. “Mercury contamination is persistent in the ecosystem as the chemical is widely used by the gold panners,” Mr Katanga said. “People get affected after eating fish from the contaminated rivers.

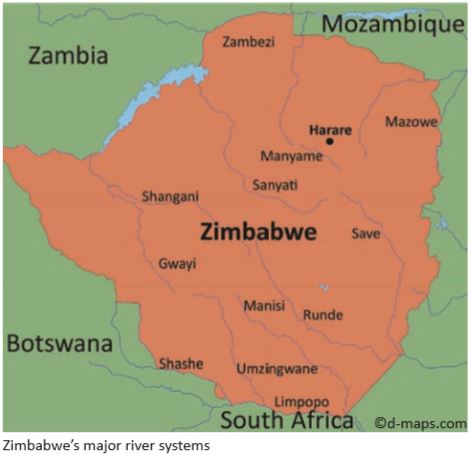

The symptoms may…present as nervous breakdown and loss of hair.” Studies by various government and independent agencies, including the Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA), have revealed that the country’s major rivers—the Mazowe, Mazowe, Save, Runde, Sanyati, Umzingwane, Manyame, Gwayi and Shashe, which spread through eight of Zimbabwe’s ten provinces—are silting, twisting and dying because of these chemicals and other practices related to mining.

“Although it is an old problem caused by the abundance of alluvial gold in Zimbabwe, gold panning has become a major environmental concern since 2000.This has caused people to flock to river banks to look for gold and as [a] result, river banks and beds have been scooped and their banks heavily burrowed, worsening the growing problem of soil erosion and silting of rivers and dams,” said the EMA report. Ben Karombo, 42 years old, has lived for more than 20 years at Manzou Farm, less than a kilometre from the Mazowe River in Mashonaland Central province in northern Zimbabwe.

“We have watched as year after year the water levels in the river and in Mazowe Dam get reduced,” said the former commercial farmworker, who took to panning after quitting his job more than ten years ago because of low wages. “The fish population has also reduced, so we are worried. But on the other hand there are no jobs and gold panning has become a way of survival for our children,” he added.

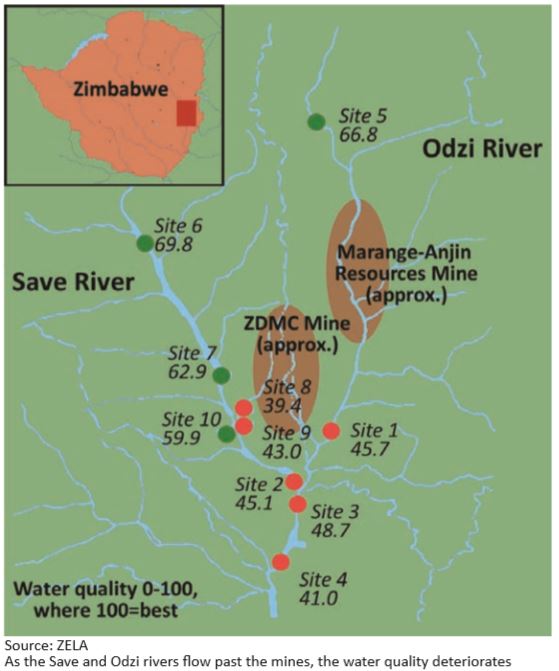

It is not only the poor who are endangering the well-being of Zimbabwe’s rivers. Diamond mining companies—including Diamond mining companies-owned Marange Resources, and Anjin Investments, a joint venture between China’s Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Company and the ZMDC—are also polluting waterways, according to a January 2013 report by the Zimbabwe Environmental Lawyers Association (ZELA).

This NGO examined diamond mining operations in the Chiadzwa/Marange areas in eastern Zimbabwe’s Manicaland province, particularly for their effects on the Save and Odzi Rivers. Residents depend on these two rivers for drinking, bathing and fishing, and use the river’s reeds in the basket-making industry.

The Odzi and Save Rivers “have been key to sustenance of livelihoods and local communities”, according to the ZELA report. “Since the start of diamond mining operations, the services that were derived from these rivers have slowly diminished as the water quality has progressively declined.

Communities cannot use water for drinking purposes anymore whilst coming into contact with the water, and mud causes an itching of the skin [sic].” Ferrosilicon, which is used to separate gold from gravel, is draining into the rivers and turning them “a red ochre colour”, according to the ZELA report.

This alloy of silicon and iron is linked to the environmental troubles in Marange, Chimanimani, Buhera and Chipinge districts in Manicaland, which have been the worst polluted. The 400km-long Ma- zowe River rises north of Harare, flows north and then north-east, where it forms part of the border with Mozambique before entering the Zambezi River. About 30,000 panners are sifting for gold along this river, including 10,000 panners who are working one ten-kilometre stretch, the precise location of which was not specified in the EMA report.

Saviour Kasukuwere, Zimbabwe’s environment minister, and Mutsa Chasi, EMA’s director-general, toured the Mazowe River basin in October 2013. Ms Chasi said that they found several mining firms, some of which are Chinese-owned, using toxic chemicals in their alluvial mining operations along the Mazowe banks.

Although these firms have legal grants to operate, the officials discovered that many are working without environmental impact assessment certificates.

As a result, Mr Kasukuwere ordered the closure of 11 mines after his visit, mostly because they were using mercury to purify gold. But the mining companies have appealed this decision to the ministry of mines. While they wait for a decision, their toxic operations continue. ZINWA has also entered the picture as it makes a small bid to help reverse the rivers’ siltation.

The water authority has trained 20 people and bought four draglines from the United Kingdom to help unclog the built-up sands in the Save, Mazowe and Insiza rivers, said ZINWA spokesperson Tsungirai Shoriwa. The programme is expected to start in early 2014.

“Most rivers have been affected and it’s not only because of illegal mining but [also] in some cases because of poor agricultural practices, such as stream bank cultivation,” Mr Shoriwa said. “The problem is countrywide, and it’s not the rivers alone: even dams are under threat because soil is being washed into the dams.” ZINWA studied Lake Kariba’s water quality in 2004.

Even back then, the survey found that mining operations had led to high levels of lead and cadmium in the lake, a major tourist attraction and the main supplier of electricity to Zimbabwe and Zambia. A 2006 EMA report assessed the impact of mine dumps, including 50 on the Zambezi basin, which feeds Lake Kariba. “Results suggest that the major environmental risks came from release of acidity, arsenic, zinc, copper, cobalt and nickel into soils and streams draining the dumps,” the report said.

Although the environment ministry and ZINWA have condemned the bad mining practices, they are not making any progress in stopping these activities. Addressing diplomats in Harare on November 14th 2013, Patrick Chinamasa, Zimbabwe’s new finance minister, tried to downplay the issue of illegal panners.

The EMA had overstated the numbers of these panners, he insisted, and claimed that only 30,000 were sifting for gold and not the 500,000 mentioned in the report. Mr Chinamasa has also never acknowledged the environmental and health problems associated with the panning. Instead, Mr Chinamasa and Fred Moyo, deputy mines minister, have said on various occasions that their respective ministries are exploring ways of legalising the panners, so that they can be taxed.

The solution is for the government to protect the rivers and the people who live nearby, the EMA’s Mr Kangata said. “We have been accused of being anti- development in various quarters for making a lot of noise about the effects of both legal and illegal mining activities,” he said.

“There is need to adopt sustainable development approaches which factor in the impact on the environment as well as the needs of local communities because the current mining trends will only destroy and impoverish local communities.”

The problems of pollution and siltation associated with unsafe mining activities by larger companies can only be stopped if the government compels them to publish their environmental assessment impact reports and forces them to adhere to environmentally correct effluent management plans, said Gilbert Makore, a lawyer with ZELA. “It can be done,” he said. “It’s just a matter of political will on the part of government, which has an obligation to protect its citizens.”