Tunisia: inflation and terrorism

Violence and volatility deter tourism and investment, the lifeblood of middle-class workers

On December 17th 2010, 27-year-old middle-class vegetable vendor Muhammad Bouazizi set himself on fire in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia. His act of self-immolation, protesting that potent cocktail of political repression and limited economic opportunity, set Tunisia ablaze with a political uprising that ignited the Arab spring. Less than a month after Mr Bouazizi’s literal spark, Tunisia’s longtime autocrat, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, fled into exile. Out of the ashes of his regime, a fragile, fledgling democracy began to arise.

In 2011 Tunisia voted for the first time in genuinely competitive multi-party elections. The moderate Islamist party Nahda (“Renaissance”) won the most votes and formed a coalition government. It began dismantling Mr Ben Ali’s regime and building a new Tunisia, but it was careful to temper expectations. As Sayid Ferjani, a Nahda leader said, “patience is key within a transition.”

He is right. Transitions from despotism to democracy are not usually an immediate economic panacea. Dictatorships are a terrible form of government, but the iron fist Mr Ben Ali used to crush dissent had one important upside: stability. Because Mr Ben Ali was so ruthless in eliminating dissent there were no challenges to his economic policy. Indeed, Aon, a London-based risk management and insurance firm, classified Tunisia as a low-risk country even in 2010, the year of Mr Bouazizi’s dramatic protest. Ultimately, during Mr Ben Ali’s 23 years of rule, investors were confident that the risk of volatility was low. They invested steadily.

The returns on those investments were spread unevenly and Mr Ben Ali’s family was the primary beneficiary. After nearly a quarter century in power, the president had accrued $17 billion in assets scattered throughout global banks, according to estimates released by the Tunisian Association for Financial Transparency in 2012.

The middle class did not prosper from the regime’s corrupt and kleptocratic practices. Instead they benefitted from stable economic growth. According to World Bank estimates, Tunisia’s economy grew at a steady 3.6% in both 2009 and 2010, the two years immediately preceding Mr Ben Ali’s departure. When his regime fell, Tunisia’s economy slipped into recession—contracting by 0.2% in 2011 amid the uncertainty of rapid political change. The country rebounded quickly, surging to just over 4% growth in 2012 before sliding back to 2.8% in 2013. World Bank estimates indicate that similarly modest growth continues.

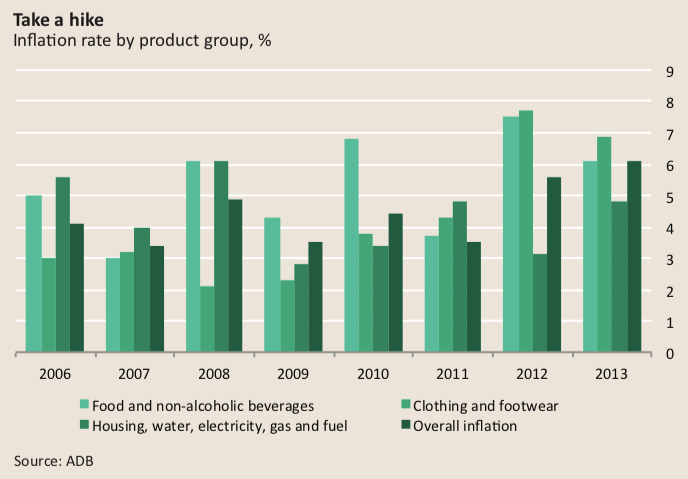

However, these positive figures belie two threats to the middle class that simmer below the surface: inflation and terrorism. The latter grabs headlines, the former does not. Middle-class Tunisians feel that inflation is the forgotten aspect of everyday life that threatens to undermine the democratic experiment.

In 2011, inflation was at 3.6%, according to the World Bank. Unfortunately, it is increasing: last year, it was pegged at 6.1%. In other words, every year the prices of most goods are rising, which is squeezing out the middle class.

According to a 2011 African Development Bank (ADB) report, Tunisia’s pre-Arab spring economy featured a robust middle class, which represented nearly 90% of the population. A subsequent report by the Tunisian Centre for Research and Social Studies (CRES)—published in 2012 and using the same metrics and definitions as the African Development Bank—found that just 70% of the population could still be considered middle class. Moreover, this share continued to shrink as more and more Tunisians found themselves sliding slowly toward poverty in the face of stiff economic headwinds, according to the CRES report.

Certain segments of Tunisian society are coping less well than others. According to the World Bank’s September 2014 report, “The Unfinished Revolution”, Tunisia’s economic woes are exacerbated by a “youth unemployment bulge” which threatens future middle class stability. In 2005, 13.3% of the country’s youth and university and technical school graduates were unemployed, a figure which more than doubled to 31.9% in December 2013, according to the bank. This skyrocketing rate is a bad omen for future middle class growth, as young people and graduates are the seeds that should germinate into a thriving middle class.

However, even for those that are employed—and have been for a long time—the threat of inflation is still daunting. Aissa, who requested that his last name not be used, is a port worker who lives in the popular middle-class al-Kram neighbourhood in Tunis, the capital. “We work just as hard as we always have and often have to work even harder,” he explains, “but it seems like every week the prices just keep going up—gas, clothes, food, everything.”

Such economic hardships often stem from Tunisia’s post-revolution political volatility. For instance, the World Bank study cited the example of Rugby, a Tunis-based clothing manufacturer. Samir Mallek, the firm’s managing director, said sales dropped considerably when the post-Arab spring government cancelled a major uniform order made by the previous regime. Rugby’s 100 employees suddenly had to work for half pay and went on strike in 2012 over wage losses. As a result, the business earned less than 30% of what it had before the Arab spring uprisings.

In turn, economic hardships often have political ramifications. When the euphoria of sweeping political change wore off and daily life resumed, family economics became the basis for more cynical attitudes. Sitting at a café in La Marsa, the posh northern Tunis suburb with a European flair, a server named Sélim admits that he longs for Mr Ben Ali to return: “I didn’t like him. But business has been terrible ever since he fell.”

Such attitudes depend on context. La Marsa, a geographic symbol of Tunisia’s elite, may have lost some of its shine as its main patron, Mr Ben Ali, is no longer calling the shots. But travel anywhere in Tunisia and others will scoff at the idea that life was better under the dictatorship. As in much of Africa, outlooks depend on whether liberty is valued over financial security andthe belief that economic woes are temporary.

A 2014 poll by the International Republican Institute, an American NGO, found that Tunisians remain divided on democracy. A slim majority, 52%, agreed with the statement: “democracy is preferable to any other kind of government.” That lukewarm support is a testament to the economic pitfalls that come with the inevitable volatility tied to a complete restructuring and rebirth of a nation’s government.

Mr Ferjani and the Nahda leadership are unsurprised by these growing pains. “Transitions are the most serious and painful periods in the lives of any nation,” Mr Ferjani admits.

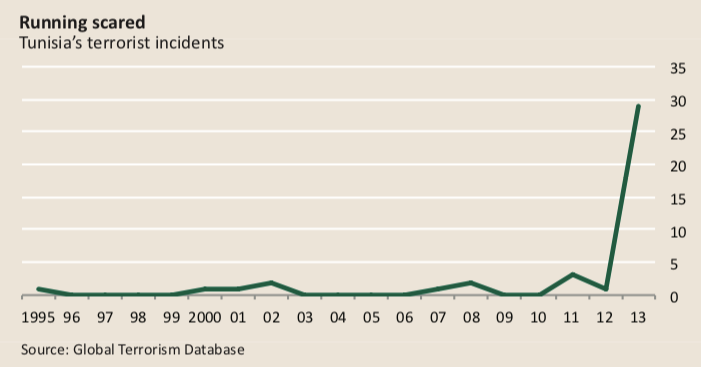

Inflation can be tackled with sound fiscal and economic policy, but a larger long-term risk looms for Tunisia’s middle class: terrorism. Political violence does not just kill people; it can also destroy economies. In 2011 the risk of violence came from the Arab spring. Sadly, while that peril has subsided, the threat of terrorism has replaced it.

Tourism revenues make up 12% of Tunisia’s GDP, supporting 400,000 direct jobs and more than 2m indirect jobs, according to the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, a London-based charity. Yet the uncertainty germinated by the Arab spring upheaval pushed tourists to flock to safer North African destinations, Morocco in particular. In 2010, 7m tourists explored the country’s beach resorts and historic south; a year later, these numbers plummeted to 4m—a catastrophic drop with severe economic fallout.

Even though these numbers are starting to bounce back as tourist confidence slowly returns, the dual threat of political volatility and economic insecurity is all too apparent; the economy could take another hit if the security situation deteriorates or another political impasse arises.

While Tunisia has escaped major terrorist attacks since 2011, two failed suicide bombings took place in late 2013, including a botched attempt to blow up tourists on a popular resort beach in Sousse, just 90 miles south-east of Tunis. Although these plots were foiled, instability and uncertainty persist, particularly as a result of two high-profile assassinations, a string of attacks by terrorists against state forces, and a recent attempted execution of an opposition politician at his home, all in the last two years.

On top of these daunting risks, the low-level civil war in Libya threatens to spread into neighbouring countries, and jihadist groups like Ansar al-Sharia have recently made explicit warnings that they will disrupt Tunisia’s national elections in October and November.

Cumulatively, current and future violence pose a major risk to Tunisia’s middle class. Volatility deters tourism and discourages investment. Both are the lifeblood of middle-class workers eager not only to retain their jobs but also to make sure that those jobs can pay the ever-rising bills.

As every other Arab spring country has withered and collapsed despite the initial blossoming of hope, Tunisia has steadily and valiantly continued to grow—albeit in fits and starts. If the country can tackle the economic threats posed by inflation and political violence, it can flourish into an Arab spring success story. However, if economic pressures continue and worsen, then the already lukewarm support for democracy could dissipate further. This would pave the way for a backslide towards authoritarianism and tempt citizens to sacrifice political liberty for the illusory promise of economic stability. It all depends on Tunisia’s fledgling leadership and their ability to deliver for the struggling middle class.