Democratic Republic of Congo: Etienne Tshisekedi

Legendary fighter with an empty victory list

Congolese opposition leader Etienne Tshisekedi, 81 years old, travelled to Belgium in September for medical treatment at a moment when Joseph Kabila, the country’s president, was expected to install a government of national cohesion.

Mr Kabila had announced the formation of this government in October 2013, at the end of a “national dialogue” organised to broaden support for the regime. This meeting had divided the opposition.

On one side was Kengo wa Dondo, speaker of the senate and leader of a joint platform of opposition parties called the Republican Opposition. When he accepted Mr Kabila’s invitation to participate, he positioned his party squarely in the Kabila government camp.

A more radical section of the opposition clustered around Vital Kamerhe and his Union of the Congolese Nation andMartin Fayulu, leader of the Citizens’ Commitment for Development (ECIDE) party. They refused to participate in the discussions because they considered them meaningless, anti-constitutional and not much more than a congress of the presidential majority. They suspected that Mr Kabila was manoeuvring to stay in power beyond 2016, when he finishes his second and, according to the constitution, last term. Messrs Kamerhe and Fayulu deride Mr Kengo as a sell-out: they think his supporters will rubber stamp the regime’s strategy as long as they can be part of Mr Kabila’s government.

Messrs Kamerhe and Fayulu deride Mr Kengo as a sell-out: they think his sup- porters will rubber stamp the regime’s strategy as long as they can be part of Mr Ka- bila’s government.

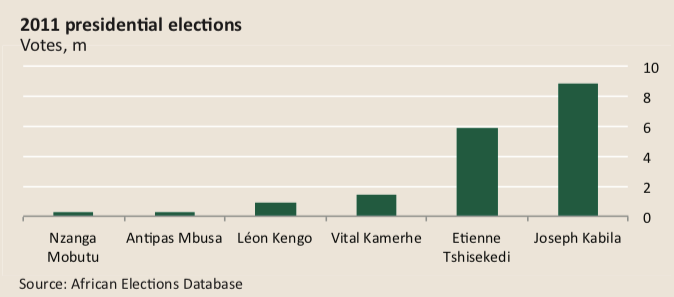

Since the November 2011 elections, the DRC’s political oppo- sition has been at sea and rudder- less. Mr Tshisekedi has declined to steer it mostly because he consid- ers himself the DRC’s elected and legitimate president. A presidential candidate in the 2011 election, Mr Tshisekedi lost with 32.3% of the vote to Mr Kabila’s 48.6% in polls that were marred by widespread allegations of fraud.

Mr Tshisekedi has simply refused to concede defeat.

This attitude has not only hindered the deployment of a coherent and collective opposition, it has also weakened Mr Tshisekedi’s own party, the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS). After the 2011 elections Mr Tshisekedi forbade his elected members of Parliament (MPs) to take up their seats until he was installed as the DRC’s rightful head of state. They ignored him. The confusion increased with the national dialogue: some UDPS MPs agreed to participate and others decided against it.

It was not always like this for Mr Tshisekedi, who cut his political teeth under Mobutu Sese Seko, dictator of the country when it was still called Zaire. Born in 1932 in the Kasai, in the south-central region of this vast country, Mr Tshisekedi started his political career as justice minister in the government of South Kasai when this diamond-rich province declared independence in August 1960. After this secession was squelched, he joined Mr Mobutu and became a minister in several of his governments. For many years, Mr Tshisekedi was a prominent member of the executive bureau of Mr Mobuto’s Popular Movement of the Revolution (MPR) party.

Considered one of the architects of this party stronghold, Mr Tshisekedi later devoted many years trying to demolish it. In November 1980 he led a group of 13 MPs who published an open letter critical of Mr Mobutu. A few weeks later, Mr Mobutu stripped Mr Tshisekedi of his parliamentary mandate and barred him from exercising his civil and political rights for five years.

This did not stop him, however, from forming his own political party, the UDPS, on February 15th 1982. One month later the police arrested him, the beginning of many years in and out of prisons and house arrest. Despite his persecution, the UDPS managed to spread rapidly throughout the country.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, many African leaders lost their importance as Western pawns on the cold war chessboard. Democracy and human rights displaced geopolitical interests in Africa. The continent’s leaders found themselves compelled to open the political boundaries. On April 24th 1990 Mr Mobutu abolished the one-party state. Mr Tshisekedi was allowed to resume his political activities, and his party was officially registered on January 17th 1991.

Mr Mobutu’s last years were very confusing: in 1991, he organised the National Sovereign Conference (CNS) and invited 2,000 delegates from the country’s various social, political and geographic interests. Its mandate was to agree on a blueprint for the country’s future. On August 15th 1992, the CNS appointed Mr Tshisekedi prime minister. This did not last long: before the year ended, Mr Mobutu installed a counter-government with his own prime minister.

Then in 1994 Africa’s “great war” began, sparked by the genocide in neighbouring Rwanda. It led to the collapse of Zaire in 1997, when the current president’s father, Laurent Kabila, backed by Rwanda and Uganda, chased Mr Mobutu out. But Mr Tshisekedi failed to recognise the relevance of this new development. He never tried talking with the rebels. They never called him either. Mr Tshisekedi faded from the political scene.

But he returned in 2002 as a delegate to the Inter-Congolese Dialogue (ICD) at the Sun City resort in South Africa, organised to unite all armed and unarmed parties in the conflict in a transitional government. Mr Tshisekedi’s ambition was to represent the opposition parties as vice-president. He failed and refused to sign the ICD’s final agreement.

Mr Tshisekedi then went to Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, to negotiate with the rebel group, Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD), which had started the war with Rwanda’s support. They had not signed the ICD agreement either. Mr Tshisekedi’s attempts to form a coalition with these rebels alienated many Congolese, particularly those in the east, where the war’s impact had been highest.

His UDPS did not participate in the transitional government that lasted from 2003 to 2006. The man who claimed to be the Congolese champion of democracy decided to boycott the elections in 2006, the first elections held in the DRC in four decades.

In December 2010, after another long absence spent in Europe for undisclosed medical reasons, Mr Tshisekedi emerged again to stand in the 2011 elections, just in time to capitalise on the anti-Kabila sentiment in Kinshasa and the western provinces.

Again Mr Tshisekedi lost. He made a political error. Mr Kabila had changed the constitution in January 2011: he limited the presidential election to one round, thus avoiding facing a challenger in the second round who might win with the support of the other losing candidates. The now aging Mr Tshisekedi felt strong enough to stand in the elections without forming a coalition with the other opposition parties, a costly mistake.

Through his brave and consistent resistance, Mr Tshisekedi evolved from one of the architects of Mobutism to a national opposition icon. In the early 1990s, Mr Mobuto outfoxed Mr Tshisekedi. When the leopard fez-wearing dictator’s fortress began crumbling in the late 1990s, the opposition leader failed to read the events.

As a result of his arrogance and his blindness in reading the political tea leaves, his nation-wide support withered to Kinshasa and then to his own Kasai. Most importantly, he failed to seize another opportune moment in 2011 when Mr Kabila was at his weakest because he thought he could do it on his own without the help of others.

Now apparently ill in Brussels, it is unclear if Mr Tshisekedi will ever return, and unlikely that he will ever again embody the people’s dismay about the lack of progress under Mr Kabila.

Today Mr Kabila, though many decades younger, is not strong—as proven by his failure to find the consensus to install the government of national cohesion. But it is unclear that any of his adversaries can beat him. Mr Tshisekedi is a legendary fighter with an empty victory list. His heavy shadow hangs not only over his own party but over the entire opposition as well.