Miners are rapacious and exploit poor African countries. Botswana is a paragon of good governance and the Democratic Republic of Congo is a hopeless basket case. That is the received wisdom—but J. Edward Conway asks if it is true.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is one of the most corrupt countries in the world, one of the most dangerous, and one of the riskiest places for foreign investment. It is also one of the planet’s most resource-rich countries. The DRC’s water resources alone could solve Africa’s energy challenges through hydroelectric power. The DRC’s agricultural prospects, if realised, could feed the continent. In terms of potential, the DRC is one of the top five areas in the world for mineral development.

The key word here is potential. Today, the DRC ranks at the bottom of countries recommended for mineral investment, says advisory firm Behre Dolbear. Instead of basking in the exalted company of Alaska and the Yukon, it squats beside Bolivia and Russia. How can the DRC realise its mineral potential? Is the solution good governance?

The answer is “that depends”. Take Botswana—also a sub-Saharan state with great mineral wealth. “Botswana is rightly held up as an example of how sub- Saharan Africa’s natural resources can—if correctly managed—play a very positive role in driving broad and transparent sustainable development,” says Gus Macfarlane, a specialist at the risk intelligence firm Maplecroft. The country ranks very low in corruption and security risks. The legal and tax environments are favourable. The government regularly passes a balanced budget. It responsibly reinvests revenue from the mining sector back into important growth sectors like infrastructure.

But is Botswana a country with good governance?

Using political plurality as a measure, the country leaves much to be desired. The Botswana Democratic Party has been in control of the government for five decades since independence in 1966, winning every election. The presidency works on a system of automatic, unelected succession. On some key social indicators, Botswana is no different from the DRC. They share, for instance, tragically low life expectancies for their citizens at birth, 53.2 years and 48.4 years respectively, according to the United Nations Development Programme. When in 2005 then Botswana-based Professor Kenneth Good described governance in the country as controlled by an elite that manipulated state media and largely ignored rural development, he was (tellingly) kicked out of the country.

Foreign investors give Botswana high marks despite an investment environment that can at times be at odds with good governance. Former President Quett Masire knew that the most important factor guiding foreign investment, particularly in the mining industry, is not good but rather stable governance. Botswana’s gains “are the fruits of goal-directed and surefooted leadership,” he said during the 1994 parliamentary elections. Those words are as true now as they were then.

Maplecroft’s Mr Macfarlane elaborates: “In addition to its diamond resources, the stability and consistency offered by Botswana’s particular political system and society has undoubtedly been beneficial in terms of attracting investment to the country.”

Unfortunately, stability and political plurality do not always go hand in hand.

What can the DRC learn from Botswana? There are many uncertainties surrounding the technical challenges of bringing ore out of the ground and processing it at a profitable margin. As a result, foreign miners look to reduce security, corruption, legal and regime risks. These risks are low in Botswana, a nod no doubt to the country’s ability to govern effectively. In the DRC, on the other hand, violence in the east continues to be extreme, corruption is pervasive at all levels of government and judicial independence is non-existent.

Complicating the situation, the DRC’s political system—though arguably more representative than Botswana’s—is plagued with uncertainty. President Joseph Kabila’s election in 2011, “while contentious”, nevertheless “prevented further destabilising the fragile country”, says Thomas Wilson, head of strategic advisory services at the industry and government advisory firm africapractice. But the next election cycle in 2016 “poses a major risk to Congolese stability,” Mr Wilson says. Mr Kabila will be ineligible to run and the head of the opposition, Etienne Tshisekedi, will be in his 80s and therefore unlikely to stand. With no clear successor, unlike in Botswana, political concern increases.

Is there hope?

Despite the DRC’s many negative risk factors, security has improved dramatically and real advances have been made in tackling corruption. Global Witness, a human rights organisation, lauded the government this year for passing a law aimed at curbing the role of mineral development in funding violence and, more importantly, enforcing the law against two Chinese mining companies.

The legacy difficulties confronting the DRC should not be underestimated.

Unlike Botswana, for instance, the country was more severely exploited in its colonial past. With independence it suffered from one of the most notorious dictators in the world: President Mobutu Sese Seko left the country bankrupt in 1997 while personally profiting to the tune of an alleged $5 billion. In addition, one of the bloodiest and most horrific conflicts in modern history—the Rwandan genocide—has scarred the DRC and significant spillover effects continue today.

The DRC can succeed in improving its governance and attracting foreign investment. The Canadian gold explorer and miner Banro Corporation, for instance, has been operating in the eastern DRC since 2004 and maintains an extensive socio- economic development programme at each of its four sites. Banro Foundation projects in education, healthcare and social infrastructure are suggested by local committees, implemented by the foundation using local labour, and then turned over to a non- governmental organisation (NGO) or provincial governmental body to operate. Along with the $2.5m that the Banro Foundation has contributed to DRC communities over the last seven years (and another $2m estimated for 2012), Banro has created roughly 4,000 jobs for local Congolese either directly or by contract, is a leading purchaser of domestic DRC goods (about $26.3m in 2011), and in the course of satisfying its own infrastructure needs, has spent over $16m on roads, bridges and other public facilities across the eastern DRC. This is all in advance of the miner actually turning a profit, which is still years away.

The indirect effects of a company like Banro on the DRC are immense. The company’s presence creates a multiplier effect in local economic development. That a foreign miner listed on the Toronto and New York Stock Exchanges can operate safely and within Canadian expectations on corporate governance has an inestimable reputational effect for the DRC as a destination for foreign direct investment (FDI). “The most important thing for us in attracting investors is getting them to the site,” says Martin Jones, chairman of the Banro Foundation. “Once they see how safe the situation is, and how well we are regarded locally, it changes investors’ perspective entirely on the DRC.”

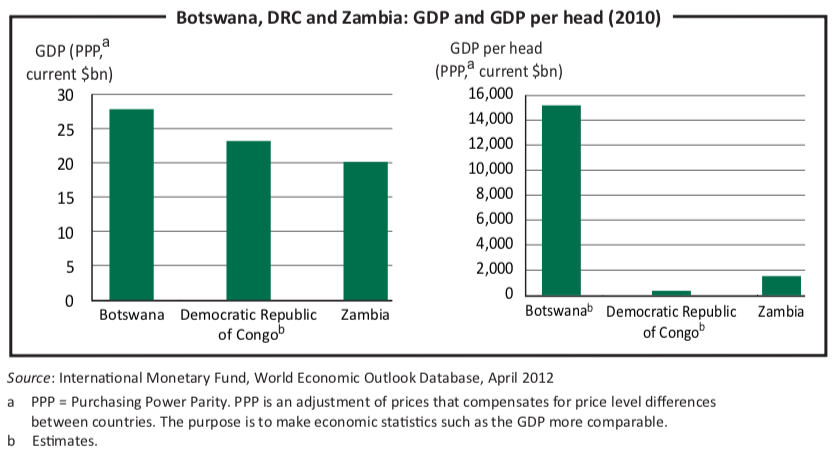

There are two issues pressing the DRC today that are good for governance and for business, and it is here where good governance advocates should focus: political plurality and taxes. Forget Botswana as a guide and instead look to Zambia: also sub- Saharan, also rich in minerals. While not nearly as positive an investment environment as Botswana, nevertheless it is a more applicable solution for the DRC.

Critically, Zambia’s recent history shows that political plurality, if managed appropriately, can actually increase investor confidence. IHS Global Insight’s Country Risk Ratings, an industry standard, downgraded Zambia’s risk score from “significant” for over a decade to the improved rating of “medium” in late 2011. Why? With Michael Sata’s election, the country passed through “the successful transfer of power to an opposition president/party” after a legacy of one-party rule, says Gus Selassie, sub- Saharan analyst for the firm. So while political uncertainty is a negative for foreign investors, when industry analysts see evidence that political plurality can be expressed in a smooth leadership transition, the result is a net positive.

The DRC faces a similar watershed moment in 2016. Under the state’s constitution, the president may serve only two consecutive terms. This means that Mr Kabila will be ineligible to run, unless he changes the constitution, which africapractice’s Mr Wilson assesses to be unlikely. Opposition leader Mr Tshisekedi will be too old to stand. So who will lead the DRC in 2016? This is a moment of high uncertainty in the country, but also one of great opportunity. The election of Matata Ponyo or Vital Kamerhe, two of the likely candidates, “would be a positive development for the investment environment, with both politicians known for their technical competence and positive foreign relations”, Mr Wilson says. If the DRC can show that free and fair elections can lead to a smooth transfer of power on a platform that includes the interests of foreign investors, the country will make significant headway in its political risk ratings.

The second convergence point between governance and investment is taxes. The DRC, like Zambia, suffers from a serious inability to collect taxes. In Zambia, for instance, the mining industry accounts for about 80% of the country’s export earnings but only 2% of the government’s annual revenue. The situation is suspected to be as severe in the DRC, if not worse. There is a dearth of legitimate governmental authority in the provinces as well as low technical knowledge of the mining sector. This translates into a government that cannot adequately assess the levels of production within the sector and therefore has no benchmark for determining what to tax.

Zambia is now participating in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), a voluntary programme in which countries and companies publish their payments and revenues (see page 32). As a result, it has discovered how large the gap is between what is collected and what should be collected, motivating the country to act. The DRC should follow Zambia’s example. More tax revenue means more money to spend on infrastructure such as roads, rail and power distribution. It is an example of good governance promoting a better business environment for investors and a better quality of life for citizens.

Industry analysts believe growth in the mining sector in the DRC will explode over the next several years—by 70% to 100% by 2016. During the last boom in the sector, from 2003 to 2008, the country’s corrupt practices and inadequate tax collection meant that the vast majority of Congolese lost out while a small group at the top profited handsomely. Zambia was no different, but today the country is trying to avoid making the same mistake twice. Good governance and mining investment do not always go together. In the DRC’s case, however, improving tax collection paired with successful elections in 2016 will go far in opening the country to foreign investors. What is good for governance can be good for miners, too.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]J. Edward Conway is an independent political risk consultant specialising in the extractive industries. His analysis has been presented in forums such as the Wall Street Journal and Foreign Affairs. He is the author of the recent monograph “Political Risk Management and Mining in Kazakhstan”. He is also a doctoral candidate at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. [/author_info] [/author]