Algeria: internet censorship and social activism

by Anne Wolf

Was it coincidence or was it deliberate? Following the January 2013 terrorist attack at the natural-gas complex in the Saharan town of In Amenas, the Algerian government once again spurned the adoption of modern mobile phone standards. The government blamed administrative procedures for its decision. Others viewed this rejection as the regime’s latest step to curb dissent.

The In Amenas hostage siege led to the deaths of at least 38 civilians and 29 militants. Shortly after this attack, newspapers reported that several high-ranking officials were concerned about the risks of third-generation (3G) telecommunications standards, particularly in the government’s fight against terrorism. The Daily Dawn, an Algerian newspaper, cited anonymous sources, presumably close to the government, that revealed “the wider security environment in the Sahel” is the real reason behind the delay. “What happened at In Amenas, including the publishing of photos, has been aimed at misleading public opinion.”

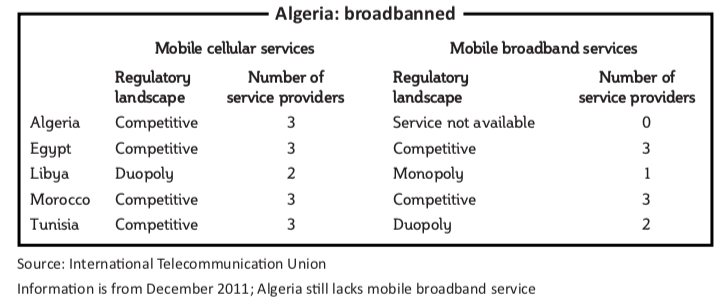

Many activists interpret the government’s ongoing postponement of the provision of 3G as yet another attempt to shackle dissent. Creaking telecommunications standards and a complex set of internet laws and regulations, particularly aimed at controlling information on social media sites, make anti-government activism in Algeria increasingly complicated. The government seems intent on hiding behind the shield of one of the world’s most archaic information and communications frameworks.

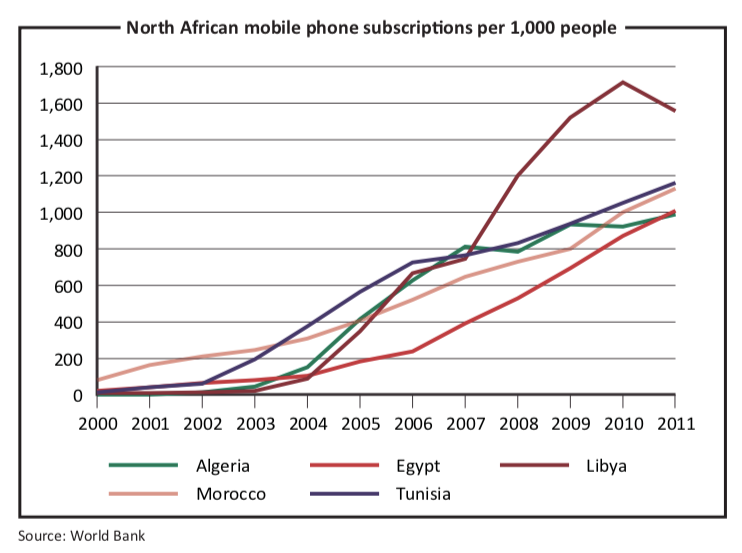

During the Arab uprisings two years ago, social media platforms surfaced as a force of popular empowerment. Bloggers throughout North Africa and the Middle East helped to rally mass street demonstrations, which led Tunisia and Egypt to revolution, Morocco to simulate reform and Libya into civil war.

Amidst such sweeping political change across the region, Algeria emerged as the only country in the Maghreb where the government retains a firm grip on the country, despite widespread poverty and high unemployment, particularly among Algeria’s youth.

Pundits attempting to explain what has come to be known as “Algerian exceptionalism” are quick to point to the country’s history – in particular the civil war in the 1990s, which cost more than 150,000 lives — to argue that Algerians favour political stability over what might end in chaos and armed conflict.

Many Algerians are hardened after their own long struggle against Islamic extremists. They watch with trepidation the resurgence of Islamists, particularly of the violent Salafi-jihadist stripe, in neighbouring Tunisia and Egypt. Many say this fear of violence was vindicated during Algeria’s 2012 legislative elections, which saw the defeat of the Islamists, although opposition forces have contested the official results. The voters apparently revealed that they favour the devil they know.

Explaining Algeria’s “exceptionalism” through its history and experience with Islamic radicalism, however, is misleading. Since the Arab Spring, social activism and demands for regime change have swollen. But le pouvoir (the power) — the government and the secret services, the Département du Renseignement et de la Securité (DRS) — have quickly battered protesters and dissidents.

Often overlooked is the other weapon the government and the DRS wield to defend their dominance: their unyielding grip on information and communications technology, particularly mobile phones and the internet’s social networks.

“With the Arab revolutions, the Algerian regime suddenly realised to what extent Facebook and Twitter could become a real threat to their authority,” explained Yacine Zaid, a blogger and senior member of the Algerian League for the Defence of Human Rights.

“The money spent on fake Facebook profiles and groups has increased dramatically over the past two years,” explained Zaid, who created his blog in 2007, becoming one of Algeria’s first bloggers. “The amount of intimidation I experience, including direct threats to kill me, has grown unprecedentedly in past months and currently amounts to several instances per day,” he added during an interview in March 2013.

This internet bullying is often called computer-generated baltagy (criminal or thief in Arabic), referring to the violent thugs that former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak unleashed against street protesters during the 2011 uprising. “The Algerian baltagy is increasingly engaged in a cyber-war with militants,” explained an Algerian blogger who wished to remain anonymous.

“One of the most important techniques to contain militants is to publish false allegations and private information — such as telephone numbers, family pictures and addresses —through pro-regime blogs and newspapers to defame and intimidate oppositional forces,” he added. “This makes it more difficult to receive reliable information from social media websites.”

Besides cyber bullying, numerous laws, regulations and the country’s timeworn infrastructure make the Algerian internet a difficult site for dissidence. In 2009, Algerian authorities adopted a law criminalising online activity that runs “contrary to public order or decency”. As a result, many regime-controlled internet cafés — the most popular places for Algerians to connect to the world wide web — now have closed-circuit television cameras recording the faces of their online customers.

Owning a website bearing the Algerian country code top-level domain, .dz, (derived from Dzayer, the local name for Algeria), is next to impossible. “Applications need to pass through meticulous bureaucratic vouching to guarantee the website will be used according to the terms and conditions set by the authorities,” explained Mohammed Larbi Zitout, a former Algerian diplomat who now lives in exile in London. “This is why most Algerian websites have other domain names such as .org, .com and .net.”

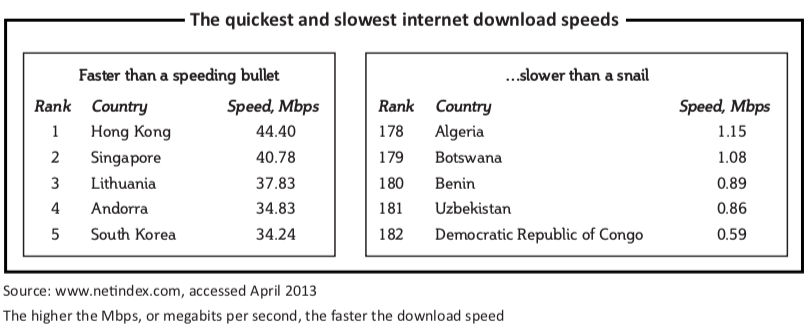

Adding to these complications is the Algerian internet’s notorious sluggishness. Most users rely on old-fashioned dial-up connections. Ookla, a US company which compares download speeds, ranks Algeria’s velocity near the bottom, 178 out of 182 countries.

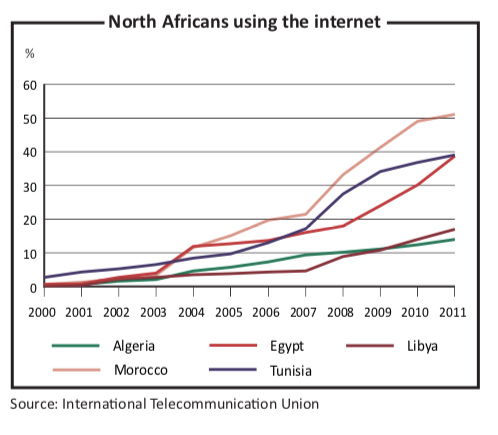

Very few Algerians go online, only 5.2 million or 14% of the nation’s 36 million population, making it one of the world’s least-connected countries, and the 34th least-connected of 55 African countries. The few that do go online are not regular, daily internet users, but casual ones, browsing the net mostly while sipping coffee at cyber cafés. The government is deliberately manipulating internet speed and connectivity, argued Zitout. “The infrastructure for a faster and higher level of internet connectivity is already there, but the regime is unwilling to use it,” he said.

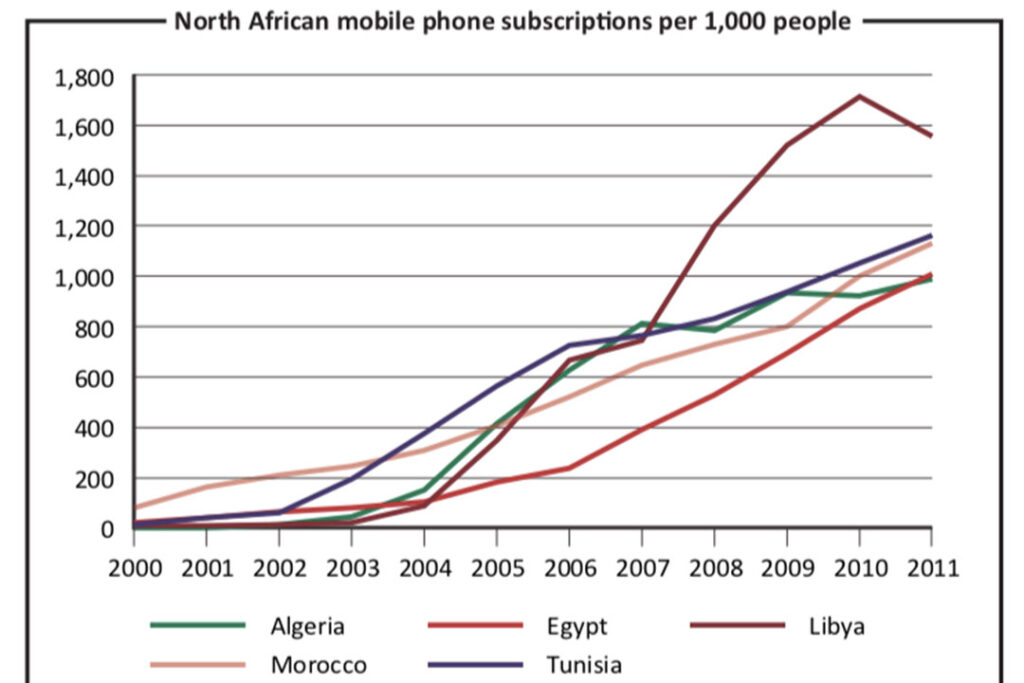

Mobile phone technology in Algeria is also limited, mostly by outdated creaking equipment and the state-run telecoms company, Algérie Telecom, that operates without competition. Mobile phones were crucial during the 2009 Iranian elections and the Arab Spring. Protestors used them not only to call demonstrators to rallies but uploaded video footage that highlighted the brutal police crackdowns.

But Algeria lacks 3G and fourth-generation (4G) telecommunications standards, which permit whizzy and faster sharing of messages, photos and videos.

Despite these barriers, insurgents still turn to the internet because newspapers, radio and television — under strict government control — do not provide a platform for protest. In 2013 Reporters Without Borders placed Algeria close to the bottom in press freedom, with a ranking of 125 out of 179 countries.

“The regime employs a ‘carrot and stick’ approach to control the media,” Zitout said. “The ‘carrot’ element is provided by symbolic charges, generous tax schemes and advertising contracts — which are often the most important sources of income — for those newspapers that ‘behave well’.” At the same time, “the regime imposes printing charges and taxes, encourages journalist intimidation and bans advertising contracts for newspapers critical of the regime. This makes most newspapers that do not adopt a pro-regime line unsustainable,” Zitout concluded.

The regime’s increasingly elaborate effort to control modern technology underlines its fear of the internet. Given the absence of a free press and modern phone and internet technology, the opposition will continue to rely on its snail-like dial-up connections to social media sites. Algeria remains “exceptional” and stable, unlike turbulent Egypt, Libya and Tunisia.