Africa’s universities and the future

by RW Johnson

A close look at the 2012–13 list of the world’s 400 leading universities compiled by Britain’s Times Higher Education magazine reveals the enormous disparities not only between the developing world and developed world, but also between Africa and Asia. Africa has only four universities on this list while Asia has 57. Africa is outgunned massively, at 14:1 overall. More importantly, the entire continent has not a single top 100 entrant.

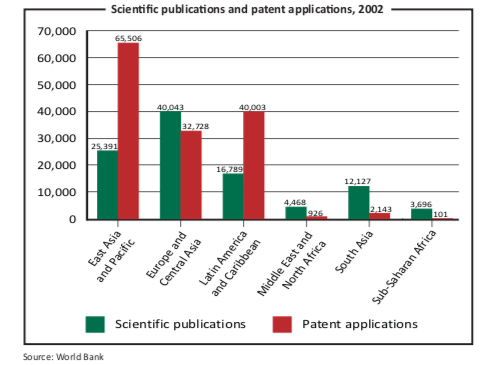

The same contrast exists if you compare scientific output. In 2002 East Asia and the Pacific accounted for 25,391 scientific publications and 65,506 patent applications, while the comparable figures for sub-Saharan Africa were 3,696 and 101, according to the World Bank. Such data is a shorthand indicator of intellectual life. Africa’s backwardness has great meaning. If the whole world is to transform into a knowledge economy, this means that either Africa will catch up or that Africa alone will constitute the third world.

In some ways Africa’s lag is surprising. By the late colonial period there were many universities of quality scattered around Africa, in Algeria, Kenya, (the former) Rhodesia, Senegal, South Africa and Uganda. Lovanium in Leopoldville in the Belgian Congo (today’s Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo) was often lauded as the best on the continent. An offshoot of the Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium, the university was set up in 1954 with aid from Belgium, the USA, and the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations. By 1958 it had acquired Africa’s first nuclear reactor.

Many other African universities had links to parental institutions in London or Paris, which maintained standards and provided a steady interchange of talented faculty. Moreover, the era of African independence saw a number of top-class radical academics clustered in Accra, Ghana, then later at Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and later still in Lusaka, Zambia.

Then came the dark ages. In many cases dictators and warlords, as if transplanted from feudal Europe, laid waste to all around them, universities included. In Liberia for instance, under first Samuel Doe and then Charles Taylor, university facilities were pillaged, the national library was totally destroyed and the number of university staff fell by 80%, according to UNESCO, the UN body responsible for education. We are not talking here of the freezes and squeezes common in Western universities but of burning, looting and mass murder.

The one-party regimes of Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere, Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda and countless others were hostile to academic freedom, university autonomy and all the other conditions for the growth of a healthy higher education sector. Essentially, the conditions for proper university life, which must always include a dissenting academy, simply did not exist throughout most of the continent in that period.

Third-world nationalism in its ascendant phase is strongly inimical to higher education. How could Chinese universities withstand the frenzies of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, the doctrine of “better red than expert” and the humiliation and torture of “bourgeois intellectuals”? It is no accident that most of the top Sinophone universities are in places that avoided that movement, such as Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Many African countries also underwent a revulsion against the old colonial culture. Everywhere universities threw off their old links with Louvain, Paris or London: academic exchange withered, the colonial universities became parochial and standards deteriorated.

One of the strongest colonial vestiges was the former oppressor’s language, which had the crucial advantage of connecting to a world culture. Algeria’s bitter war against the French left a mood of intransigence, which continues to infect higher education with dire results. The University of Algiers, established in 1909, was able to call on good French-language teachers in a wide range of subjects so long as it remained Francophone. Post independence, Arabisation was pushed all the way; French in higher education was eliminated by 1997. Not only were students and academics cut off from French academia, but now there is a huge shortage of competent Arab teachers and key academic books in Arabic. Webometrics, an internet site which ranks universities beyond the conventional top 400, places the two best Algerian universities, Université des Sciences et de la Technologie Houari Boumediene at 2,971 and the University of Constantine at 3,225 in its 2013 index.

Morocco illustrates the opposite. By 2006 it offered over 40 relocated French university programmes up to master’s level. The numbers of Moroccans studying abroad fell from 59,000 in 2003 to 42,000 in 2006, according to the World Bank, as students flocked to these internationally recognised degree courses. In the same period, the number of foreign students studying in Morocco doubled, with over 5,000 usefully paying fees to its universities. Other institutions throughout Africa have also faced this choice between nationalist fundamentalism and globalisation.

The University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa is now repeating Algeria’s mistake: it is attempting to make Zulu co-equal with English as a language of instruction and administration. Arabic is at least an international language. The irony is that under apartheid every so-called “tribal college” in the black homeland areas opted for English. The attempt to push Zulu at what was once one of South Africa’s top three universities has had utterly ruinous effects: staff and students have fled and standards have nosedived.

“I am just about the last survivor,” said a senior professor who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Inevitably, standards have fallen. The requirement that everyone must do a module in Zulu is scaring people away—they fear this is only the first step. A lot more of the university staff, black and white, would leave if they could.”

The World Bank has played an unhelpful role in the past. Its 1986 report on the returns to investment in education suggested that Africa should promote primary education over both secondary and tertiary. This encouraged many African presidents, who had decided that protesting students and querulous academics were a mixed blessing, to neglect their universities.

The World Bank recognised this major mistake and in a 2008 report argued that top-class universities are the engines to promote growth in knowledge-intensive and high-tech endeavours. But whether universities can become truly top-class depends both on the quality of the primary and secondary education systems which feed students to them and, most important, money.

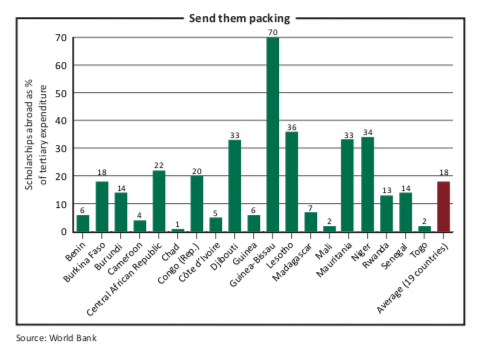

The World Bank’s 2010 report, “Financing Higher Education in Africa”, criticises the enormous resources devoted to sending Africans to study abroad: they amount to 18% of all African higher education expenditure. Such scholarships, as the World Bank puts it, “are usually allocated to beneficiaries from the most privileged social groups, and the criteria for the award of these scholarships often lack transparency”. Moreover, of the $600m that external aid donors gave to African higher education in 2002–06, 70% was spent paying fees for Africans studying abroad. Evidence suggests that African.

students are more likely than others to stay on in the countries whose universities they have attended, contributing to the brain drain (see page 17). African countries would be far better off strengthening their own universities and attracting students from abroad.

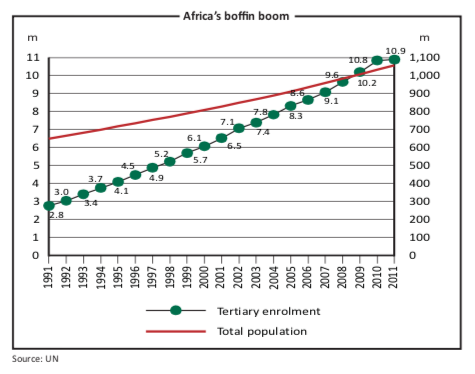

African universities have often expanded too fast. The continent’s universities hosted 10.9m students in 2011, up from 2.8m in 1991, according to the World Bank. Such expansion, as the Bank points out, inevitably comes at the expense of faculty wages and building maintenance. It leads to overcrowding, declining investment in research and non-replacement of necessary books, journals and equipment. The result is a fall in quality and a diminishing ability to retain qualified staff. This leads to faculty moonlighting in other jobs (and doing no research) or emigrating. Now, less than 35% of lecturers in African universities have master’s degrees, doctorates or their equivalent, according to the World Bank.

This headlong expansion is politically popular and short-sighted. Having fewer but higher quality graduates would serve Africa better. This is hardly implausible: if the quality of decision-making by, say, African civil servants could be sharply increased, the effects on welfare could be enormous.

South Africa is the critical country when it comes to higher education in Africa, for it has the lion’s share of the continent’s scientific publications and patent applications. But the story is otherwise unhappy. Last year three South African universities came under state administration while a fourth was placed under an assessor, which is much the same thing. While the rest of Africa is recovering from one-party hegemony, South Africa is not. In a statement issued at its 2012 national conference, the ruling African

National Congress (ANC) declared it “has a responsibility to promote progressive traditions within the intellectual community, including institutions such as universities”. This means that academic freedom and university autonomy are more circumscribed than they were under apartheid; that universities practise very strong forms of affirmative action in their admissions, their faculty appointments and sometimes even their marking; and that they are under pressure to admit large numbers of semi- literate students churned out by a dysfunctional school system, with a consequent lowering of standards across the board.

The government’s determination to ram students into the universities is thus a major threat to what are still the continent’s leading universities. Blade Nzimande, Minister for Higher Education, says he wishes to quintuple the number of students in tertiary education by 2030. This exactly replicates the mistake the World Bank has warned against.

Africa needs South Africa to preserve and increase the quality of its universities so that they can play a role in assisting the continent’s many promising starter- universities. At present no one is listening to the World Bank’s injunctions—do not expand too much, focus your efforts, retain and increase quality. As a result South Africa looks as if it is determined to repeat the mistakes made elsewhere in Africa. Should this happen it would be a continental, not a national calamity. It is too soon to draw final conclusions: the game is still in play. But the beginning of wisdom would be a realisation of just how high the stakes are.