How gravity became Lesotho’s most precious resource

by Simon Allison

Lesotho is a tiny mountainous country completely enclosed by South Africa. One of the world’s poorest, its economy is almost entirely dependent on South Africa’s for employment and for the purchase of its main natural resource, water. Its inhabitants, the Basotho, share a number of historical, linguistic and cultural similarities with surrounding tribes, who are all now South African.

But, resoundingly, Lesotho is not South Africa. This has irritated its bigger neighbour many times over the years.

The low point in relations came in 1998, when South Africa’s caretaker president, Mangosuthu Buthelezi, while filling in for Nelson Mandela and deputy Thabo Mbeki, authorised a brief but ignominious invasion of Lesotho at the government’s request. Within less than a week Lesotho’s 2,000 mutinous and ill-trained troops had comprehensively outfought and embarrassed their South African counterparts.

Meanwhile, the high point in relations — quite literally — has been a sustained decades-long cooperation between the two governments to move some of Lesotho’s water to where South Africa needs it most: its industrial heartland in Gauteng province.

South Africa, one of Africa’s most populous nations, as well as an industrial and agricultural powerhouse, is a thirsty country. But South Africa’s rich stock of natural resources does not include an over-abundance of water.

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates South Africa’s internal renewable water resources (river flows and groundwater from rainfall) for 2011 at 44.8 billion cubic metres, which is on the dry end of the international spectrum. Of this, South Africa uses about 31%, a figure that is more impressive than it sounds because South Africa ranks high among the world’s most efficient users of available water. The country consumes most of its annual supply, without much left over for emergencies like droughts.

Gauteng province, the country’s most populous and by far its thirstiest, depends on the Vaal River System, which also feeds the North West province. “This system supports the core of the South African economy and population [in Gauteng],” said Mike Muller, former director of the Department of Water Affairs. “Probably 60% of the economy and maybe 40–50% of the population benefit from this system. It’s very important for South Africa.”

Any disruption to Gauteng’s water supply is an existential threat to the South African economy. This is more than a hypothetical danger. Chances are that there will be a major interruption to the province’s water supply sometime between now and 2020. Water experts in the area operate on the working assumption (predicting rains is not an exact science) that there is a major drought in the area once every 50 years. The last major drought affected Gauteng in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

This drought risk became obvious as early as the 1950s, and engineers started looking for possible solutions. There were many on offer: water in the Orange River could be pumped northward, a major undertaking involving roughly 600 km of pipelines, for example; or South Africa could put a lot more money into re-using water. But there was a more obvious solution: Lesotho. The mountain kingdom is blessed with more rain than its two million citizens can possibly use. Most of it, however, runs off to feed the Orange River at Aliwal North — too far from where South Africa needs it most.

Using the large amount of Lesotho water that would continue flowing into South Africa at Aliwal North seemed an obvious solution, explained Mr Muller to Africa in Fact. “Unless Lesotho tries to drown itself, Lesotho can’t keep all of that water. It flows. That’s the thing about water that people sometimes don’t understand. This isn’t mining where you mine a regular stock. This is a regular, repeated flow.”

If only the flow could be diverted, South African engineers reasoned, then gravity could do the rest. Of all the options available, it would be the cheapest, most energy-efficient and produce the best quality water. Over the decades the original concept of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) has crystallised into a complicated system of dams and diversions that bring Lesotho’s water to South Africa’s industrial heartland by redirecting it from running into the already well-watered Eastern Cape.

There is an important distinction to make here: the water does not belong to Lesotho, and if it were left unchecked, it would flow into South Africa anyway. South Africa is paying Lesotho for the privilege of using its territory to divert the flow. The payment terms make this explicit: South Africa pays Lesotho a percentage of the money it would have cost South Africa to pump the water about 570 km northwards from Aliwal North into Gauteng.

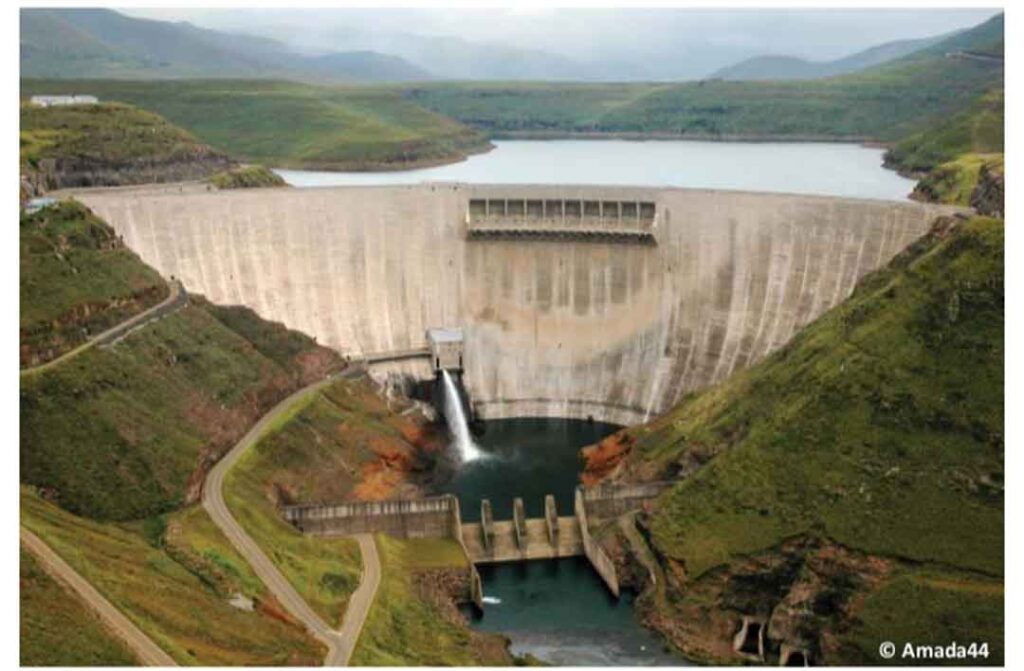

So far, the ambitious, multi-phase project is still in its infancy. South Africa has built two dams — Katse and Mohale in the Maluti Mountains in Lesotho — along with an accompanying network of tunnels, weirs and reservoirs. These funnel 24.7 cubic metres of water per second into the Vaal River System. South Africa has also built and is operating the Muela hydropower station, which channels 72 megawatts of electricity into Lesotho’s grid. Together, this constitutes Phase I — a good start, but not nearly enough to guarantee South Africa’s water security.

This is where Phase II comes into play. On 16 May 2013, officials from both countries agreed in principle to begin the project’s next phase, which involves yet another dam, more tunnels and a pumping plant. This will cost the South African government about R9.2 billion (US$900m), and is scheduled for completion in August 2020 (a bizarrely specific date given that tenders have not even been issued). If all goes according to plan, this will add more than half again to the volume of water that is already diverted into the Vaal River system. More precisely, it will add another 14.9 cubic metres per second to the current flow rate, according to figures provided to Africa in Fact by the Lesotho Highlands Water Commission.

The agreement is a vital part of the South African government’s vision for long-term water security. This explains why Edna Molewa, the water affairs minister, said that she is confident that South Africa is not going to run out of clean water any time soon. “Our water strategy and our plans for the future are all geared towards sustainability and security of supply,” she said.

The project is just as important for Lesotho, if not more so. LHWP royalties in 2011–2012 accounted for 5.9% of the government’s total revenue, according to the finance ministry (and some 2.7% of gross domestic product according to Africa in Fact’s calculations). This does not include any of the taxes and customs duties generated by the project, which would have added up to another tidy sum.

So, it is all good news, right? South Africa gets the water it needs; Lesotho gets the money it needs; and everyone is happy? Not quite. Political scientist Jo-Ansie van Wyk of the University of South Africa has written about the regional security implications of the ever-increasing cooperation between the two countries. She has a few concerns.

“The primary regional security implication of projects such as this is that states become more dependent on other states,” she told Africa in Fact. “In the case of South Africa, we are increasingly dependent on Lesotho for water. Therefore, our responses to insecurity in Lesotho are almost hyper-responses. Anything that threatens our water supply makes Pretoria sit up straight.” Van Wyk lists South Africa’s 1998 invasion as a case in point.

“Secondly, these projects are often associated with widespread corruption, which can undermine both South Africa and Lesotho’s international standing,” van Wyk added. “Thirdly, Lesotho’s political environment has been unstable for some time. Local actors may want to use the project to attract the attention of the governments of Lesotho and South Africa. I visited the Katse Dam a few years ago and was surprised to see how little security there had been at the dam and the surrounding village.”

Of these three issues, corruption is probably the most pressing. Van Wyk describes the project so far as a kind of “liquid arms deal”. This is in reference to South Africa’s notoriously corrupt Strategic Defence Acquisition in 1999, in which a number of high-profile South African leaders have been implicated in major financial irregularities during the tender process.

International Rivers, an NGO, agrees: “Massive corruption was discovered on the LHWP in 1999, when more than 12 multinational firms and consortiums were found to have bribed the chief executive of the project. After the chief executive himself was found guilty, three major construction firms were put in the dock; thus far, three have been found guilty and charged, and one has been debarred at the World Bank,” said Lori Pottinger, the group’s spokesperson.

Oddly enough, this incident had a silver lining. Unlike the arms deal, some of the corrupt businessmen and officials involved did stand trial and were forced to pay reparations. There were consequences. This gives good ground to hope that this example will keep the next round of tenders clean. The project’s cross-border nature also aids accountability. Two sets of officials, two prosecuting authorities and two judiciaries make it harder to get away with any dodgy business.

Apart from corruption, the impact the construction will have on homesteads and villages is potentially devastating. Phase I has already forced a number of people out of their homes (estimates range from a few hundred to over 20,000). Compensation in the form of new housing and sometimes cash settlements forms part of the agreement between South Africa and Lesotho, with the necessary funds earmarked for this purpose. But critics say the compensation is slow in coming. Some resettled people have complained that their new land is smaller. Others have reported hostility from host communities unhappy about having to share their communal resources.

Supporters of the project, however, are adamant that the two governments are doing all they can to help affected people — and that the overall benefits outweigh the costs. “The other side of the resettlement argument is what happens if Lesotho gets a quarter of a billion rands less in royalty payments, what happens if the economy in Gauteng slows down appreciably, who loses from that?” Muller asked.

We are unlikely to find the answer to these rhetorical questions. The governments of both Lesotho and South Africa show every intention of committing to the LHWP’s long-term future, which includes two more phases after the completion of Phase II. Progress will probably be slower than advertised and more expensive, as such massive infrastructure projects usually are, but it should eventually be completed.

In the meantime, both governments must be vigilant in ensuring that there is a minimum of corruption and that affected communities are properly compensated. This is in each country’s best interest, of course. Complications will only delay the increased flow of water down the mountains into Gauteng, and delay the flow of money moving the other way —money being the one commodity to which the laws of gravity do not apply.