Women in Africa’s parliaments: save us some seats

by Karen Hasse

Women’s political representation is vital to securing greater gender equality, feminists and others argue. Africa has made great strides in electing more women to its parliaments. Four African countries are among the top ten countries with the highest numbers of women in parliament. But even in these countries, gender inequality persists. Many of Africa’s women are still constrained by sexist laws and cultural beliefs that infringe their rights.

More women in parliaments “make it more likely that legislatures will repeal regressive policies that deny women their basic human rights and create new laws that increase women’s ability to realise their rights,” Jennie Burnet, associate professor of anthropology at the University of Louisville, wrote in an e-mail interview with Africa in Fact.

Rwanda is Africa’s economic and social success story. Much has changed in the last decade in this tiny country, the site of Africa’s worst genocide in 1994. In 2003 Rwanda overtook Sweden to become the country with the highest proportion of women in the House of Deputies. Women made up 48.8% of its lower chamber of parliament, compared to Sweden’s 45.3%.

In 2008 it became the first country to have a female parliamentary majority of 56.3%.

“The increase in women’s political representation in Rwanda has had a dramatic impact on ordinary Rwandan women’s lives,” wrote Ms Burnet, who conducted field research there between 1997 and 2009. Women parliamentarians have been able to help enact a number of important laws improving the lives of ordinary women.

In 1998 when women made up only 17.1% of Rwanda’s legislature, they worked together with women’s groups in civil society to make sure that Rwanda’s marriage laws provided inheritance rights for women and girls. When women parliamentarians became a majority in 2008, they successfully made domestic violence illegal. A year later, marital rape was criminalised.

Rwanda is one of the few countries in Africa where gender equality has extended beyond these basic legal protections. In 2011 women’s labour force participation rate was higher than men’s by two percentage points at 88.3%, according to the World Bank. The ratio of girls to boys in primary and secondary education is 1:1. The proportion of firms with female participation in ownership is 42.5%.

The rest of Africa, however, lags behind Rwanda. The latest World Bank figures show that women in 2012 made up only 21.4% of the lower houses of parliament in sub-Saharan Africa and 17.9% of these chambers in North Africa.

Many obstacles block women from politics. They often lack political connections. They are also less educated, mostly because they are shut out of schools or do not spend as much time in school as men. In only 15 African countries, out of 44 surveyed, are women expected to have at least as many years of schooling as men, according to the World Bank.

In only 15 African countries, out of 44 surveyed, are women expected to have at least as many years of schooling as men, according to the World Bank.

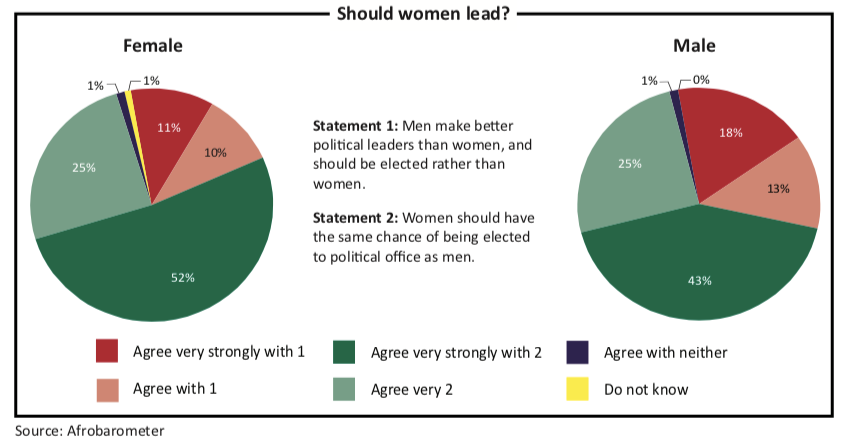

Ironically, men are not alone in holding such views. In surveys conducted in 22 African countries in 2011 and 2012, 31% of male respondents and 21% of female ones believed that men should be elected rather than women; and that men make better political leaders, according to Afrobarometer, a polling group.

When women are elected, there is no guarantee that they will improve ordinary women’s lives. They may find themselves lone voices in overwhelmingly male legislative chambers. In some cases, political parties will have chosen them as tokens, and they have little say over policy.

As a result, many have argued that a critical mass of 30% female representation in national legislatures is necessary for women to have sufficient power to begin advancing gender equality. Having more women in parliaments can also have an important symbolic effect, making society accustomed to women leaders.

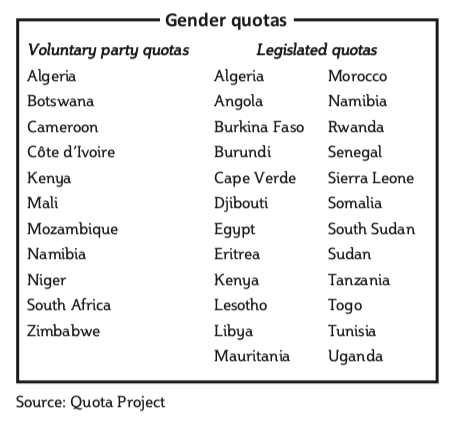

According to the World Bank, ten countries in Africa had this 30% critical mass in 2012: Algeria, Angola, Burundi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Senegal, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania and Uganda. Of these, all but the Seychelles use gender quotas to boost the number of women in parliament.

More than 100 countries use some form of gender quota, either legislated or a voluntary party quota, according to the Quota project, an online gender quota database. Of these, 32 are in Africa.

Women’s rights advocates see quotas as a strategy to accelerate female political influence and to guarantee that their rights are on a par with men’s. Others oppose quotas because they artificially propel women into elective office. Candidates should be selected on merit, they argue, not just because they are women.

But achievements are not evenly distributed between the sexes because women have fewer opportunities than men, feminists argue. A system based solely on merit reinforces the discriminatory social structures that favour men in the first place.

Quotas and other types of affirmative action may be unnecessary if the state provides equal opportunities to all groups. But women’s lives are often also controlled by their fathers, brothers and husbands. It is questionable, however, whether government should legislate to bring about change in private family relations.

But while some female parliamentarians have been able to push through a few important laws to improve the lives of ordinary women, the results have been uneven. Women make up 36% of Tanzania’s parliament, but legislators here have failed to pass laws that ban child marriage, or fully criminalise marital rape. In Uganda, where 35% of parliamentarians are women, one of the highest rates in Africa, women still do not have equal property rights. Ms Burnet blames this failure on widespread male opposition. Yet, without these basic legal protections for women, achieving educational and economic parity is even more difficult.

Measuring the effect of women in parliament on gender equality is a difficult task, while their contribution to legislating for gender equality has been ambiguous. But the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), eight socio-economic goals to be reached by 2015, can be used to gauge whether the ten African countries with more than 30% female representation have made more progress than other nations in promoting gender equity. They have not.

MDG Three aims to promote gender equality and has three targets: increasing the number of women in national legislatures; improving the ratio of girls to boys in primary, secondary and tertiary education; and increasing the number of women in wage employment in the non-agricultural sector. Of the ten countries with the highest proportion of women in parliament, only Rwanda is on track in improving the ratio of girls to boys in education; and only South Africa is on track in boosting women’s share in wage employment outside of agriculture from 41.1% in 2000 to 44.5% in 2010, according to the World Bank.

None of the ten countries with more than 30% female representation are on track to meet MDG Five of improving maternal health.

Overall, having more women in parliament has not resulted in greater progress in reaching the MDGs that target women.

Nor have women parliamentarians in most of these countries really been able to change society’s attitudes towards women.

South Africa has had over 30% female representation since 2004. But the higher number of women legislators has not made women less vulnerable to gender- based violence, which has continued unabated. Sexual offences against women were higher in 2009–10 and 2010–11 than in 2006–07, though they decreased marginally in 2011–12, according to the South African Institute of Race Relations.

Some women in South Africa also feel that the police and justice system treat them unfairly. In surveys conducted by Afrobarometer between 2010 and 2012, 11% of female respondents said that the police and courts “always” treated women unequally, while 27% said this was “often” the case.

“Having women fairly represented in parliament also needs to move beyond the numbers…to the implementation on the ground for ordinary women in our communities and society, who continue to be the most vulnerable,” said Ntombi Mbadlanyana, country manager for South Africa at Gender Links, an NGO. “Having women in parliament has not necessarily changed the attitudes of men toward women and their capabilities,” Ms Mbadlanyana added.

Perhaps this is where Rwanda got it right. The constitution stipulates a 30% quota for women in all decision-making bodies at the local, regional and national level. But in both parliamentary elections since the quota was enforced, the number of women elected has far surpassed the required 30%.

“Women’s opinions are valued in public forums whereas before they might have been dismissed,” Ms Burnet explained. “Male kin have come to recognise that women can make important decisions, manage financial issues, and play a role in leading the household.”

Though Rwanda has succeeded, its tragic history explains part of this achievement. In the immediate aftermath of the 1994 genocide, which left over 800,000 people dead, 70% of the surviving population was female. As a result, women took on many traditional male roles as community leaders and primary income earners.

These circumstances have contributed significantly to eroding oppressive cultural conceptions of gender roles. But these perceptions persist in many other African countries and quotas have not been enough to fully empower women.

Other measures are needed in addition to quotas to change people’s thinking patterns, particularly in societies where female leadership is taboo.

These include a greater focus on education as a mechanism to challenge prevailing gender norms; and government and business commitment at all levels to consider women’s situations and promote equality in all policies, especially those relating to parity in education, income and labour participation. Without such additional efforts to change the way societies view women, female parliamentarians will offer little more than a shiny veneer.