Africa’s digital landscape is rapidly changing. Over the past seven years, digital news sources have almost doubled. According to the Afrobarometer, four in 10 adults across 43 countries surveyed report turning to the internet or social media a few times a week or daily for news. Interestingly, the rise in digital sources coincides with a decrease in trust in news.

Digital media, meanwhile, is not only reshaping information landscapes but is also influencing politics. Alongside this is the resurgence of Russian and Chinese interest in Africa. The expansion of China and Russia is often analysed through economic and military influence, but to what extent do these countries influence media trust in Africa and what are the implications thereof?

The 2023 Digital News Report revealed that there had been a global reduction in trust in news. The report also found that digital platforms such as TikTok, YouTube and Instagram were becoming important sources of information for news, especially in the Global South. While most Africans (69%) use radio and television (54%) either every day or a few times a week for information, between 2014/15 and 2019/2021, the number of respondents who got their information from social media or the internet nearly doubled from 24% to 43%.

This year, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS) reported that Russia hads led at least 189 known campaigns targeting 39 African countries – 72 campaigns in West Africa, 33 in East Africa, and 25 in southern Africa. The report also found that about 60% of disinformation campaigns on the continent were foreign state-sponsored, primarily by Russia, China, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar.

Disinformation, which is defined as the intentional dissemination of false information with the intent of advancing a political objective, blurs the line between fact and fiction. Often, the aim of disinformation is less about convincing the targeted audience and more about a strategy to confuse citizens. This negatively affects social trust, the ability to engage in politics fairly, critical thinking and, ultimately, the functioning of democracy. And while dis- and misinformation are not unique to Africa, vulnerable information systems make African countries more susceptible to manipulation

On 21 April 2022, Reuters reported that Ethiopians queued outside the Russian embassy in Addis Ababa to help Russia in Ukraine. The Ethiopian foreign ministry and Russian embassy both made statements refuting claims that Russia was deploying Ethiopian volunteers. Notably, there were no reports of Ethiopians offering their services to the Ukrainian embassy. Perhaps this can be explained by social media rumours in Ethiopia that claimed those who fought in Russia would be paid $2,000 and possibly work for Russia after the war had ended.

Russian disinformation has been particularly evident in West Africa, sometimes culminating in coups. Burkina Faso is an illustrative example: in 2022, the country experienced two coups in nine months. On 30 October 2023, the Washington Post reported that Russian operatives created fake social media accounts exploiting the legitimate fears and frustrations of Burkinabe. These accounts glorified Russian President Vladimir Putin, advocated for closer ties between Russia and Burkina Faso, and overstated the success of the Wagner Group. Given the meticulous nature of Russia’s disinformation campaigns, it is unclear if Russia orchestrated the September 2022 coup or merely capitalised on the unrest. However, it is believed that the first coup leader, Lt Col Paul Henri Sandaogo Damiba, faced pressure to align more closely with Russia.

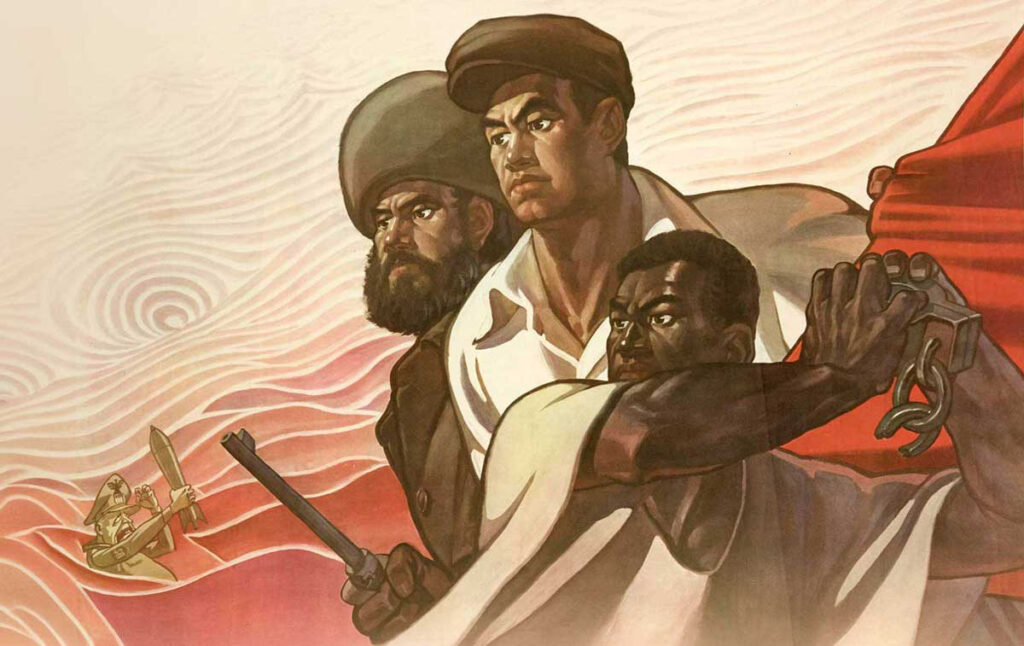

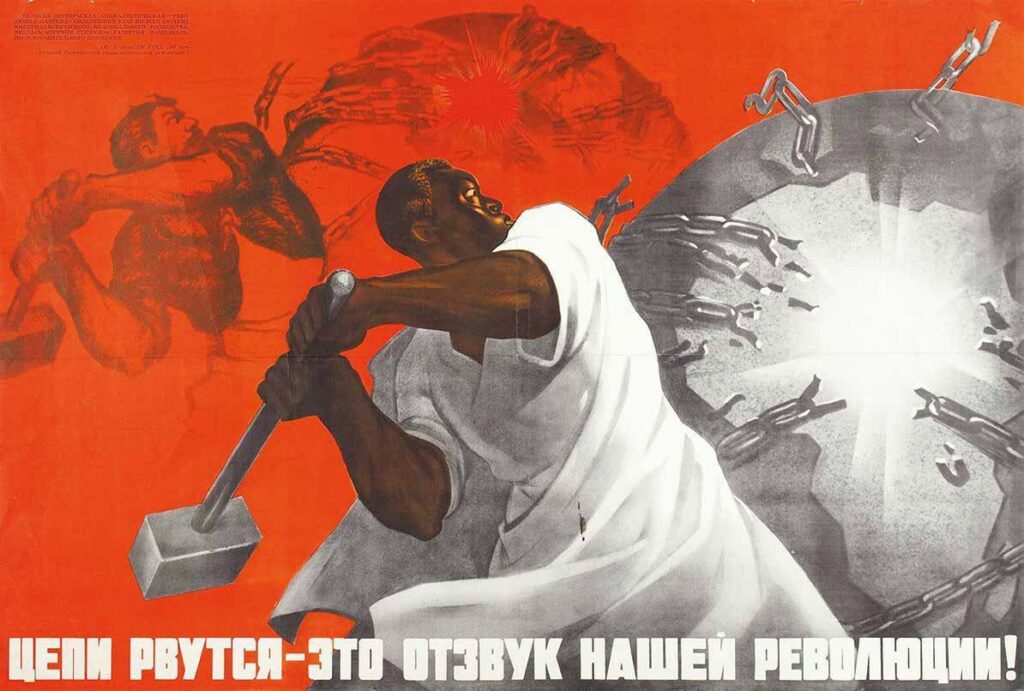

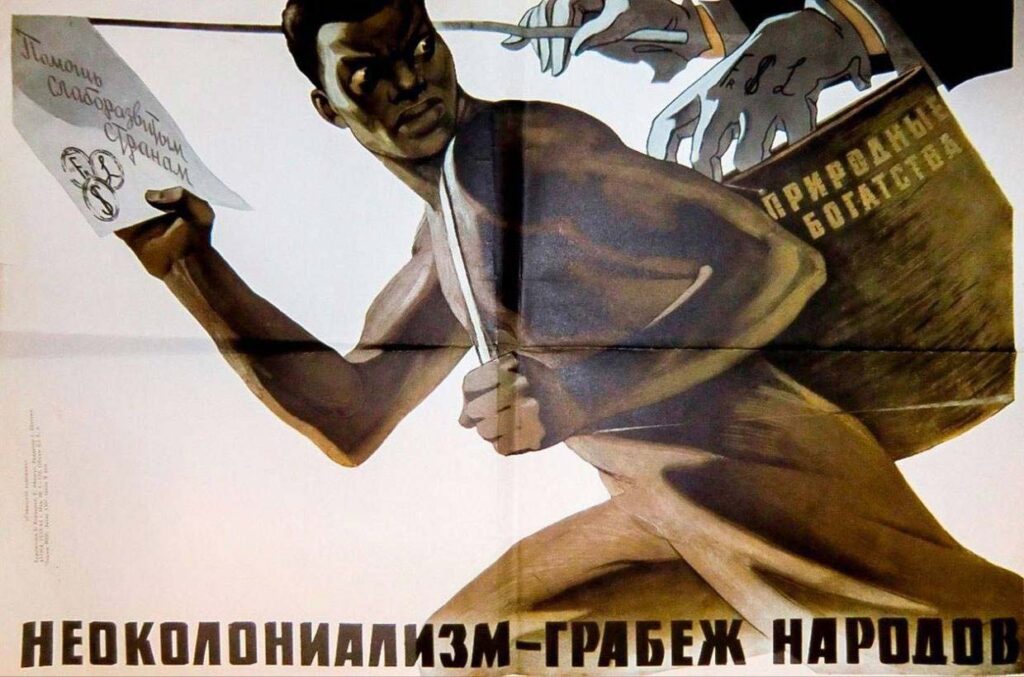

Campaigns like these also use local actors groomed to influence opinion, online networks, and Russian state media. For example, Russia employs pro-Russian platforms to sub-contract African media and social media influencers to spread false information that is disseminated in African languages. Like China, Russia pushes the narrative that it has no colonial baggage and presents itself as a long-time friend and big brother.

Entertainment is another tool used in these campaigns. The 2021 Russian war film, Le Touriste (The Tourist), portrays Russian mercenaries as heroes fighting corrupt governments and jihadis on behalf of Central African Republic citizens. Similarly, animated comic content targets youth on platforms such as X, Instagram and WhatsApp. These campaigns use both fake and real people, making it difficult to detect and remove them. By using local actors, disinformation appears more relatable and locally authentic, complicating identification efforts.

Another example is Facebook removing several inauthentic, coordinated accounts operating in eight African countries in 2019 that had been engaged in long-term disinformation and influence campaigns that promoted Chinese and Russian interests. Dr Shelby Grossman, a research scholar, led the team that worked with Facebook to identify and analyse Russian-linked disinformation in Africa. During this investigation, Facebook pages linked to the late Yevgeny Prigozhin, leader of the Russian mercenary military Wagner group, were discovered. These pages were found to consistently promote content supportive of the incumbent authorities in various African countries, including Mozambique, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Madagascar, and Libya. Grossman’s findings revealed that the 73 inauthentic pages were posted 48,000 times, were liked by over 1.7 million accounts, and received more than 9.7 million interactions from users.

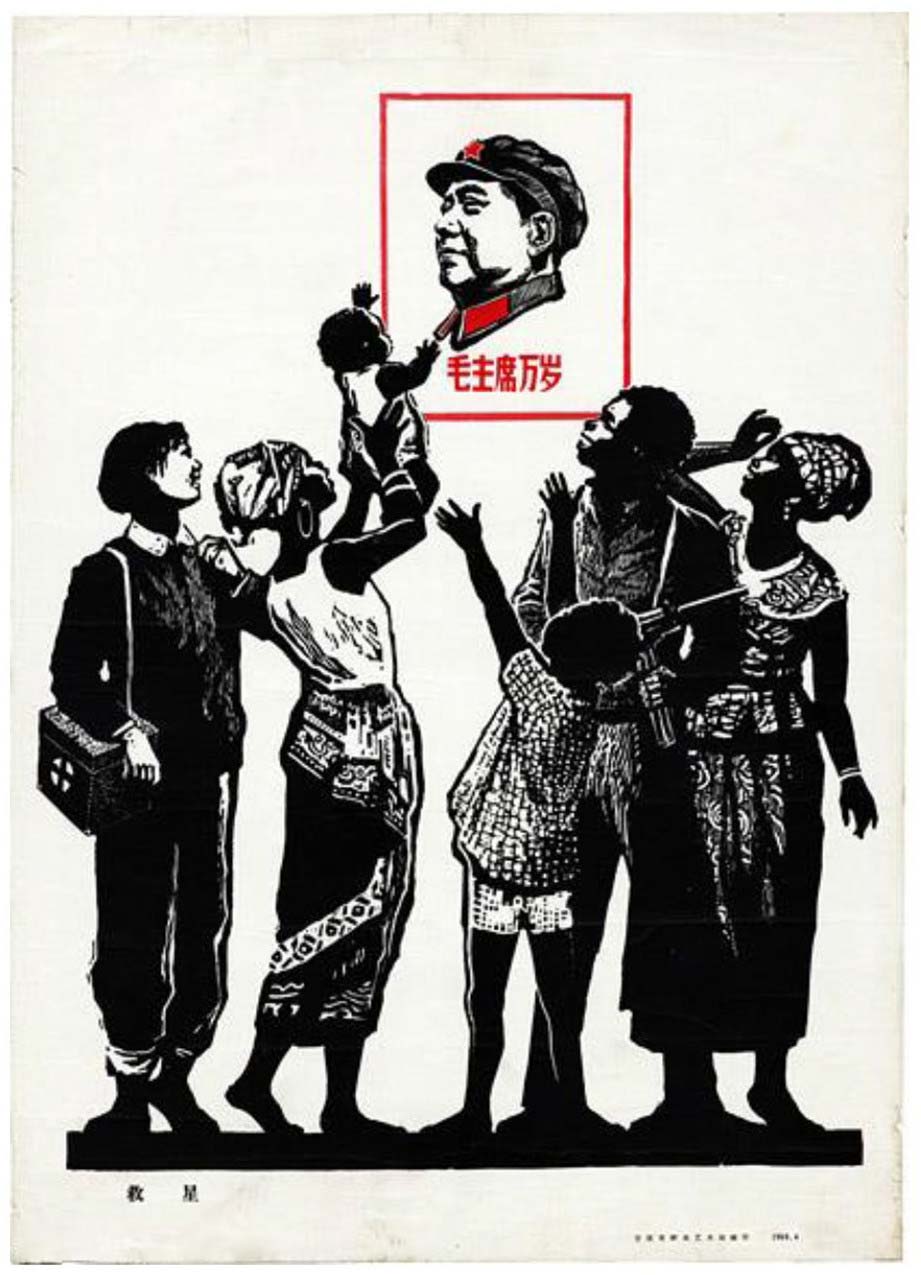

Compared to Russia, China’s influence is more institutionalised. This involves training African journalists and editors through Chinese programmes aimed at discouraging criticism of African presidents and their ministries, along with Chinese officials. Additionally, China adopts a strategy of acquiring ownership shares in African media houses and directing their editorial practices towards the Chinese model.

When asked whether the government should have the authority to restrict or prohibit the dissemination of false news or information, hate speech, or content critical of the president, 77% of respondents surveyed by the Afrobarometer expressed support for government intervention to limit the sharing of false news or information.

Following this, 7% believed that the government should restrict the dissemination of hate speech, while 47% said the government should block any news, information, or opinions of which the government disapproved. On average, 60% of Africans assessed the media as either completely or somewhat free. Perceptions were the highest in Gambia (82%), Namibia (80%), Burkina Faso and Tanzania (78% respectively), and Tunisia (77%). In contrast, perceptions were low in Liberia (19%), Gabon (22%) Eswatini (35%), Togo (45%) and Côte d’Ivoire (46%).

Similarly, 65% of Africans said that the media should be free to publish any views and ideas without government control. It is worth noting that perceptions were the highest in the strongest and most democratic countries, including Botswana, Mauritius, Seychelles, Gabon, South Africa, and Ghana. Notably, Eswatini features in the top 10 countries that support media freedom. Support for media was predictably lower in non-democratic countries, with Mali at 41%, Morocco at 46%, and Sudan at 47%.

The Afrobarometer Round 9 survey (2021-2023) revealed that 65% of Africans believe that the media should be free from government control, while 77% supported government efforts to limit the spread of false news. In addition, 51% of respondents viewed China’s influence in their countries as somewhat or very positive. Those findings highlighted a nuanced perspective, whereby Africans valued media freedom but also recognised the need to curb misinformation.

Despite these insights, it’s challenging to draw a direct correlation between public perceptions and the increasing influence of China and Russia, given the absence of longitudinal data. Nonetheless, the survey underscores the importance Africans place on credible information amid growing disinformation campaigns.

As Africa’s digital landscape evolves and access to digital sources increases, improving information systems to mitigate misinformation is crucial. The consequences of failing to do so are already evident in political instability, such as coups in West Africa and skewed electoral outcomes. These examples demonstrate that disinformation poses a severe threat to democracy in Africa, potentially more so than in other regions due to the continent’s unique vulnerabilities.

The Afrobarometer survey, alongside growing disinformation campaigns by foreign powers, demonstrates that African countries must prioritise the enhancement of their information systems. Ensuring the dissemination of credible information is essential to safeguarding democratic processes and countering the detrimental effects of disinformation.

Education will also play a central role in curbing disinformation. An educated population is better able to hold their government accountable and critically evaluate the information they receive. Advances in artificial intelligence have made misinformation and disinformation more sophisticated, further emphasising the need for educational initiatives that enhance critical thinking and media literacy.

Dr Mmabatho Mongae is a Lead Data Analyst at Good Governance Africa (GGA), where she plays a key role in developing innovative, data-driven tools to improve governance and urban management across the continent. Her work includes the Governance Performance Index (GPI), a first-of-its-kind assessment of local municipal performance, and the African Cities Profiling Project, an initiative aimed at building a comprehensive information bank to assist cities in enhancing service delivery for both citizens and enterprises. She has a PhD in International Relations from the University of the Witwatersrand, and is a research fellow at the Centre for Africa China Studies.