Africa’s brain gain

by Ronak Gopaldas

Femi Badeji left his native Nigeria nearly 20 years ago and moved to the United States. He earned an MBA at Wharton, one of the US’s top business schools, and then worked as an engineer and later as an investment banker on Wall Street.

He recently returned home because he says the time is ripe to play a part in Africa’s growth story. “It took me around 17 years to make the move back to Nigeria but I had to position myself in such a way that I could help fix the continent while also achieving my own dreams,” he said. “When I moved back to Africa in 2009, I had achieved all that I wanted to achieve education- and career-wise in the US and I was ready for the next phase of my career.

“I can now contribute to the continent’s development by using my engineering and financial skills to help improve infrastructure, as well as channel funding to priority areas within the economy. Apart from the hard skills, [making a] contribution also involves taking a stand and being vocal to let people know that there are better ways to do things than the way they are currently being done.”

Mr Badeji, now working as an investment banker in Nigeria, is one of an unknown number of highly educated Africans who are returning to the continent. He is part of a trend that some are calling a “brain gain”. They are fleeing the West’s shrinking economies, lured back by Africa’s booming growth. Like Mr Badeji, some return not only to capitalise on career and business opportunities, but also out of a genuine sense of patriotism and the desire to return home and make a difference.

Data confirming that African émigrés are returning to the continent do not exist. Still, there is a swell, albeit anecdotally, of educated Africans returning home. It is most apparent in fast-growing Nigeria and the politically stable countries of Ghana and Kenya, according to Mark Mobius of Franklin Templeton Investments. The return of their skills, knowledge and experience may signal the reversal of the brain drain which beset many African countries in the latter half of the 20th century as the brightest minds left the continent.

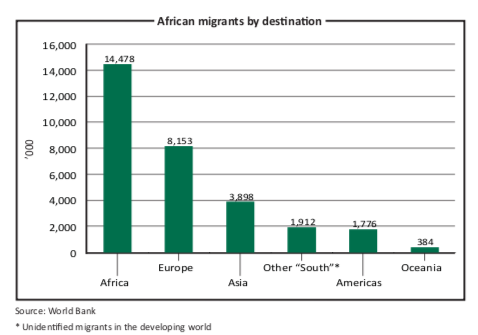

Africa’s diaspora comprises 30.6m people, according to Anne Kamau and Mwangi Kimenyi, researchers at the Brookings Institute. Half of these have moved to other African countries, while 8.2m Africans live in Europe and 2m in the Americas.

Poor remuneration and harsh living and working conditions in the three decades after decolonisation (1960–90) pushed about 40% of African professionals and specialists to emigrate to Europe, the Middle East, North America and Oceania (the small islands of the Pacific) in search of greener pastures, according to the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). The combination of inflation, political instability (often brought about by coups d’état), high poverty, poor governance, corruption, tribalism and nepotism also drove many to emigrate.

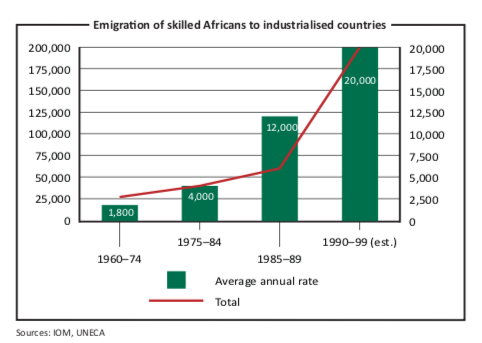

Between 1960 and 1975 an estimated total of 27,000 highly qualified Africans left the continent for the West, according to UNECA. This number increased to about 40,000 between 1975 and 1984, and then almost doubled by 1987, representing 30% of Africa’s highly skilled stock—educated and trained personnel whom Africa can ill afford to lose.

The continent lost a total of 60,000 professionals (doctors, university lecturers, engineers, scientists, etc.) between 1985 and 1990, and has been losing an average of 20,000 annually ever since, according to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

Relative political stability and economic growth over the past decade have been key catalysts in attracting émigrés to return. Armed conflicts and coups are declining in Africa while more countries are holding multi-party elections.

Average annual real GDP growth for sub-Saharan Africa has risen steadily from 3.5% in 1997 to 4.8% in 2012, and is projected to reach 5.6% in 2013 and 6.1% in 2014, according to the International Monetary Fund. The continent’s share of global FDI has also grown from 3.2% in 2007 to 5.6% in 2012, according to a 2013 report by Ernst & Young.

A 2010 IOM report found that about 70% of East African migrants, mainly Ugandans, Kenyans and Tanzanians in the United Kingdom, were willing to return home permanently. Jacana Partners, a pan-African private equity firm in the UK, Kenya and Ghana, surveyed African students at the top ten American and European business schools. Their study showed similar results: more than three in four hope to work in Africa upon graduation.

The monetary cost of African migration is significant: currently only 20,000 scientists and engineers in Africa are serving Africa’s population of about 1 billion.

Between 1960 and 1975 an estimated total of 27,000 highly qualified Africans left the continent for the West, according to UNECA. This number increased to about 40,000 between 1975 and 1984, and then almost doubled by 1987, representing 30% of Africa’s highly skilled stock—educated and trained personnel whom Africa can ill afford to lose.

The continent lost a total of 60,000 professionals (doctors, university lecturers, engineers, scientists, etc.) between 1985 and 1990, and has been losing an average of 20,000 annually ever since, according to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

Relative political stability and economic growth over the past decade have been key catalysts in attracting émigrés to return. Armed conflicts and coups are declining in Africa while more countries are holding multi-party elections.

Average annual real GDP growth for sub-Saharan Africa has risen steadily from 3.5% in 1997 to 4.8% in 2012, and is projected to reach 5.6% in 2013 and 6.1% in 2014, according to the International Monetary Fund. The continent’s share of global FDI has also grown from 3.2% in 2007 to 5.6% in 2012, according to a 2013 report by Ernst & Young.

A 2010 IOM report found that about 70% of East African migrants, mainly Ugandans, Kenyans and Tanzanians in the United Kingdom, were willing to return home permanently. Jacana Partners, a pan-African private equity firm in the UK, Kenya and Ghana, surveyed African students at the top ten American and European business schools. Their study showed similar results: more than three in four hope to work in Africa upon graduation.

The monetary cost of African migration is significant: currently only 20,000 scientists and engineers in Africa are serving Africa’s population of about 1 billion.

Many returnees also start businesses in their home countries, creating much- needed jobs and career opportunities for fellow countrymen.

Aly-Khan Satchu was born in Mombasa, Kenya, read law at the University of Durham and worked for 15 years in the City of London. After spending nearly three decades abroad, he quit his London banking career at the age of 40. He arrived in Nairobi in August 2006 to capture what he called the “low-hanging fruit” in the Kenyan economy and thus take an active part in the African growth story.

Mr Satchu, a prominent investment and financial guru, believes the brain-gain momentum is snowballing. He encounters returnees or people looking to return to Kenya between three and four times a week, he says, and has seen a marked uptick in this trend since his return.

Several initiatives are trying to build on this positive momentum. The World Bank’s African Diaspora Programme has projects ranging from knowledge sharing among émigrés to remittances for economic development. Another is the Digital Diaspora Network Africa, an online resource for Africans abroad interested in contributing to the continent’s development. The Homecoming Revolution is a third. Originally conceived to encourage the return of South African professionals living abroad, it is now expanding throughout the continent.

The Homecoming Revolution has worked with businesses and in-country returnees to host over 30 international events to “showcase jobs, products and services back home, not to mention entrepreneurial, property and investment opportunities and bring the continent’s best and brightest back home”, said Angel Jones, Homecoming’s CEO. Their interactive website provides advice on moving back and resettling.

At a governmental level, Nigeria has set aside $5m for diaspora activities since 2012, including a payment of $2,500 to any professional based abroad who decides to return home. Reliable statistics are hard to come by in Nigeria so it is difficult to confirm the number of people who have collected their $2,500 stipend.

Kenya looks towards its diaspora as a tool to help create employment and curb poverty. It has created a website to identify the skills and expertise of its citizens operating abroad. Senegal has a ministry devoted to diaspora issues. Tanzania is also looking at plans to harness its émigrés’ talents and wealth.

Africa’s brain gain has the potential to create financial, institutional and societal benefits. It can equip public sector institutions and private commerce with qualified and experienced personnel and thus enhance economic development. Expanding and profitable businesses can foster the growth of the middle class, create a wider tax base, and generate a more active and vibrant civic society, all of which bring long-term benefits to a country.

RONAK GOPALDAS is a director at Signal Risk, an exclusively African risk advisory firm. He was previously the head of country risk at Rand Merchant Bank (RMB) for a number of years, where he managed a team who provided the firm with in-depth analysis of economic, political, security and operational dynamics across sub-Saharan Africa. He holds a BCom degree in philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) and a BCom (Hons) from the University of Cape Town (UCT). He also has an MSc in finance (economic policy) through the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London.[