Many in the music industry believe African music to be the source of most of the music we hear today

African music is as diverse and broad as the continent itself, with thousands of musical styles ranging from North African, with its strong Arab and Islamic influences, to that of the west, central and sub-Saharan regions of Africa. Along with indigenous instruments and traditional forms, there are modern variations, countless interpretations and a multitude of crossovers; and it’s clear that African music is not simply confined to the continent.

Actually, many in the industry consider African music to be the source of most, if not all of the music we hear today. While this is difficult to prove, it’s clear that African music has had a massive impact on contemporary music and that many significant styles of the past two centuries are rooted in the Motherland.

Solomon Linda’s Mbube, also known as Wimoweh and The Lion Sleeps Tonight, for instance, is one of the most covered songs of all time. Composed by Linda, a Zulu migrant worker, and first recorded in 1939, this song has traversed oceans and been reinterpreted by an unexpected array of artists. Interestingly, it’s because of Henri Salvador’s 1962 version, Le Lion est Mort ce Soir, that many people in France today are still under the misconception that this South African classic is authentically French.

In the 1960’s, South African artists like Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela made their mark in Europe and the US, bringing African music to western audiences. Makeba was among the first African musicians to receive worldwide recognition, and Masekela made an indelible print on the evolution of American jazz.

In 1972, Paris-based Cameroonian artist Manu Dibango recorded Soul Makossa and a year later, after being picked up by some New York DJs, it became a worldwide dance-floor hit, and the first disco song ever to make the Billboard Top 40. Decades later, the song’s catchy rhythmic chant, Mama-ko, mama-sa, maka-mako-sa was appropriated by two major pop artists – first appearing in Michael Jackson’s 1993 hit Wanna be Starting Something and later Rihanna’s Don’t Stop the Music.

Decades on, Linda’s estate is also finally the beneficiary of royalty payments after a campaign by veteran South African journalist Rian Malan. And following a lawsuit, Dibango is also one of the few artists of African origin to ever reach such a settlement.

Soul Makossa may have sparked the disco movement, but ultimately its groove is pure funk. This is confirmed by the bassist Idris Badarou, a seasoned session musician who’s played with the best – working with funk masters like Fred Wesley and touring the world and recording with contemporary African stars like Nigeria’s Femi Kuti and currently Algerian superstar Rachid Taha.

Born of Beninese parents, Badarou spent his formative years in what was then Dahomey, but has lived most of his life in France. He describes himself “as a true Parisian, but I’m also an African”.

“We’re all influenced by music from other continents,” he told me in an interview in Paris. Working with many of the giants of African music, he insists, is first of all about making music. “We’re just making music. If it comes to the African music then it’s African music, but at first we’re just making music!”

Funk, Badarou says, is essentially African music. “That’s how I got hooked on funk, because when I first heard the funk groove, that’s when I heard African music.” He credits James Brown for launching funk in 1971 with Sex Machine. Later in his life, after he met Bootsy Collins, who became his mentor, he learned that these typically funky basslines emerged when Bootsy had come back from a tour to Nigeria with James Brown.

Bootsy had spent time at Fela Kuti’s legendary venue, The Shrine, in Lagos, Nigeria, which is where, according to Badarou, he learned the style he, Badarou, describes as “stretching out in the rubber band”. “Bootsy’s baselines were really African – because of the groove. For me, funk was African music.”

The 1970s also saw groups such as the Senegalese family band Touré Kunda settle in Paris. Singing in different languages to reflect the multicultural mix of the people of their region, Casamance, they released their debut album in 1979, which was the first of many that went gold. “When we arrived, we started listening to different music – French music, South African music inspired by Miriam Makeba,” says one of the Touré Kunda brothers, Sixu Tidiane Touré. “So we thought we could use our folk music and we started to work on our repertoire from Casamance, to play our own music.

“It was the first time that African people living in France had seen African people play in their own language in the country of Victor Hugo,” says Touré. Credited with transforming the perception of African music in Europe, they were soon noticed and invited to collaborate by the likes of Talking Heads and Carlos Santana – who, incidentally joined them again recently, on a salsa remake of their hit Emma as featured on their new 2018 album, Lambi Golo.

The 1980s also saw the rise of artists such as Senegalese superstar Youssou N’dour, Salif Keita (the “golden voice of Mali”), and “world music” initiatives such as Peter Gabriel’s Real World studio and label. In 1987, the Guinean singer Mory Kanté released Yeke Yeke as a single from his third studio album, Akwaba Beach. The song was an instant hit, reaching number one on the European charts in 1988, and becoming the first African album to sell over a million copies internationally.

African music had always flourished on its own ground, but with increasing globalisation it began to expand beyond its previously regionalised presence. In the late 1980s, the term “world music” was established as an industry category. While many differ as to the source of this ridiculously broad global genre, some saw it as a derogatory way of subjugating all music from non-western cultures. Yet ironically, its strength and longevity lies in its vagueness.

Senegalese singer and guitarist Baaba Maal is one such critical voice. He has been widely quoted as saying, “I think that African music must get more respect than to be put in a ghetto like that. We have something to give to others. When you look to how African music is built, when you understand this kind of music, you can understand that a lot of modern music that you are hearing in the world has similarities to African music. It’s the origin of a lot of kinds of music.”

With a large immigrant community and the world-music boom of the 90s, Paris became the international centre of African music. And although the digital era is affecting the way we consume music, this city remains the global epicentre of African music. As we have seen, African artists have had huge commercial success in recent years – but it is usually through their collaborations with big names from the US or Europe.

With over 35 million albums sold worldwide, Senegalese-American Akon, sits solidly at number one on the Forbes Africa’s 2017 list of the top 10 most bankable artists on the continent. Some critics question whether the music from artists like him is really African. What does that mean? For me, and beyond the hype, distinctively African music has an underlying pulse that sustains and remains, even when times are tough. Only a handful can ever become superstars.

The sounds of African music have inspired maestros and music makers across the globe. Consider Afrobeat, the musical genre that originated in the 1960s as a blend of Ghanaian highlife, Nigerian Fuji music, with American funk and jazz influences.

Percussion-driven, with complex polyrhythms and vocal chants, the style was made famous by Nigeria’s outspoken musical activist, the saxophonist Fela Anikulapo Kuti.

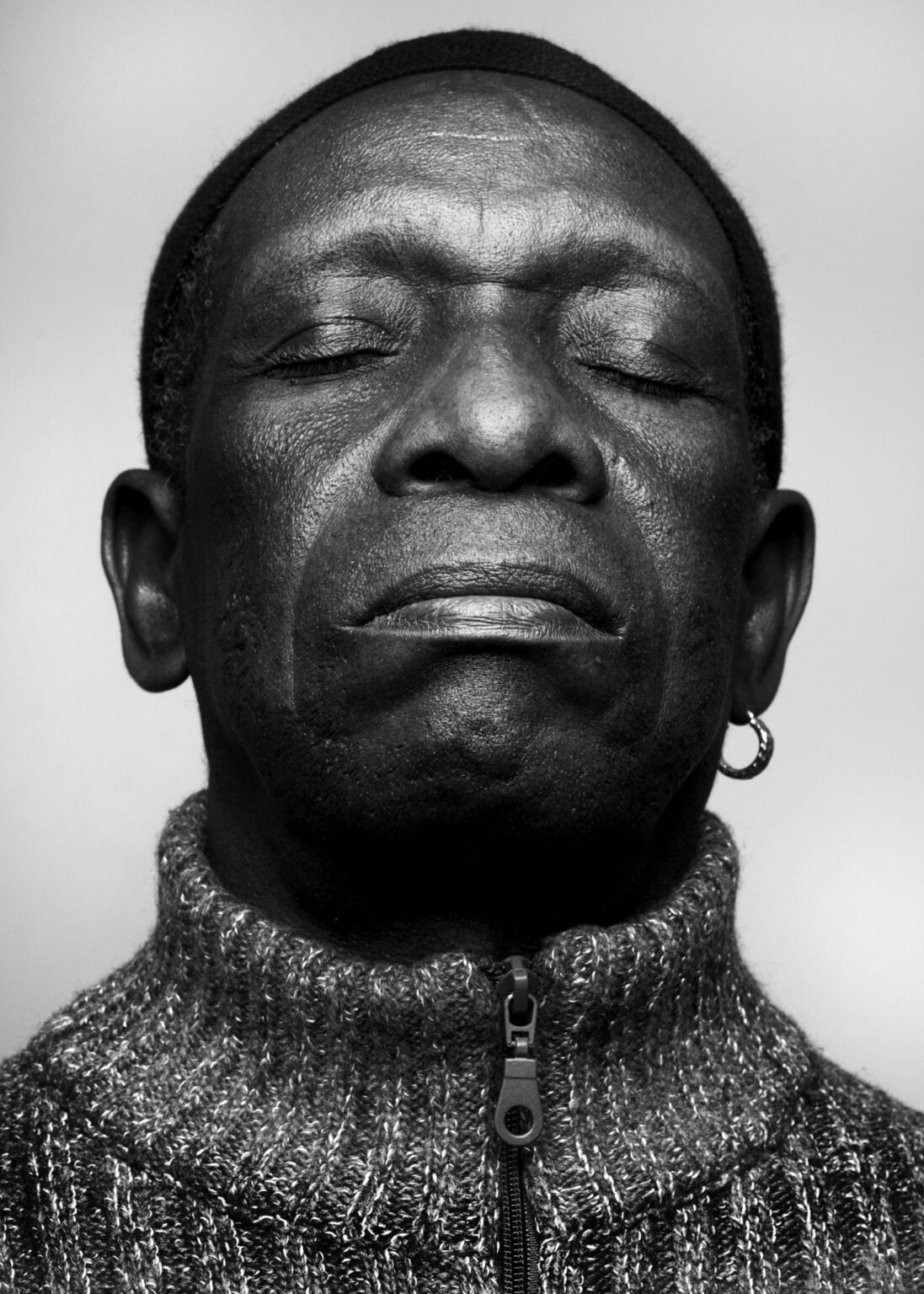

Fela Kuti, who saw himself as a messenger who used music as a means of advocating for social change, was undoubtedly Afrobeat’s frontman. But it was the inimitable drummer Tony Allen who put the distinctive beat in the Afrobeat sound. Fela Kuti died in 1997, but Paris-based Allen is as prolific and energetic as ever. He continues to influence contemporary musicians and performs with a mastery that satisfies jazz purists and a dynamism that captivates youthful audiences. Recently, in June this year, he played to a packed house as part of the Paris New York Heritage Festival. With two distinct sets – the first a jazz tribute to Art Blakey and the second a solid Afrobeat excursion – he proved that at the age of 78 one can still be progressive and relevant.

More than half a century later, the Afrobeat sound, deemed “underground” for so long, lives on stronger than ever. Fela Kuti’s legacy has been immortalised on Broadway in Fela!, a musical about his controversial life, a creative contribution that celebrates his pioneering blend of jazz, funk and traditional African rhythms. Today Afrobeat is bigger than ever, with groups on every continent and artists from even the most unexpected countries.

Along with all this, recent years have seen the integration of Ethiopian music into the cultural landscape of Paris. Two groups worth mentioning in this regard are Akalé Wubé and Arat Kilo; both groups began, independently, about 10 years ago. Initiated by young French musicians, they found inspiration in the “golden age of Ethio-groove”, with its big-band sound, horn sections and vocal arrangements. Akalé Wubé started by covering music from the Éthiopiques series – an archival collection of compilations initiated in 1997 and released by the Paris-based record label Buda Musiqualso – but also drew from the pop idiom of the 1960s and 1970s. Immersed in Ethiopian music, the band increasingly explored collaborations with musicians and dancers from the rest of Africa and Europe, performing over 200 concerts in Europe, Asia and Africa over the past decade.

Significantly, the band collaborated with Girma Bèyènè in the latest release of this series with the 2017 album Girma Bèyènè & Akalé Wubé – Éthiopiques 30: Mistakes On Purpose. An Ethiopian legend but almost forgotten, Bèyènè hadn’t performed for over 25 years, and the collaboration began when the group invited him to perform a song at their monthly residency, L’Hermitage. Founding member of Akalé Wubé Etienne de la Sayette told me that it was “a very emotional experience”, which sparked more performances.

With the help of Francis Falceto, the producer of the Éthiopiques series, they collected all of Bèyènè’s songs, some of them live recordings, which Akalé Wubé adapted for this album. The living legend had never released as a solo artist. “I was born again because of you,” he told the band. The collaborating musicians have had successful shows in Ethiopia as well. “We are proud to play this music, but what’s important isn’t to do it like others, but to do it your [own] way,” De la Sayette told me. “We are French, we do it our way.”

Fabien Girard and Samuel Hirsch, of the group Arat Kilo, originally connected through their common love of Ethiopian music. They drew inspiration from the “swinging Addis seventies”, referenced “the grandfather of Ethio-jazz”, the veteran multi-instrumentalist Mulatu Astatke, and explored the specific structure of Ethiopian music scales. Over the years, they’ve increasingly integrated West African, Afrobeat, funk and hip hop elements into their blend of Ethiopian groove. For their latest album, Visions of Selam, they’ve join forces with Boston hip hop artist Mike Ladd and Malian songstress Mamani Keita.

While they focus on touring with Arat Kilo, both founding members also have other projects rooted in African music. For Girard, it’s playing balafon (a traditional wooden xylophone) with Balaphonics – an outfit that combines West African rhythms with western brass sections. Hirsch, meanwhile, is a member of the Bim Bam Orchestra, a 15-piece collective that combines Fela’s Afrobeat with jazz, hip hop, ragga and Caribbean rhythms. “There is a whole big family in Paris,” says Hirsch, “musicians that play African music, mixing it with music from around the world.”

Other groups such as Abdul and the Gang borrow from the east, combining Morocco’s Maghreb and Chaabi melodies in a blend of Afrobeat groove, which they call Gnawa funk. Likewise, the Lyon-based group Super Gombo infuse their Afrobeat sound with jazz, Senegalese mbalax and other West African elements.

Such cross-cultural integration is nothing new in Europe, but some say that the approach fell short in the past, with not enough appreciation of the authenticity of sources. But in my view, the current wave of cross-cultural work does aim at an inherent understanding of the African music from which it gains inspiration. This authenticity can be attributed to the African presence in France, and as Hirsch explains: “We live alongside people coming from Africa everyday, everywhere in Paris and we love it.”

He points to a Parisian tradition of mixing music from Africa. “Radio Nova has been doing it for about 30 years now, so there’s a tradition. We have it in our blood. We’ve been listening to African music since we were little, so it comes to us naturally.” Indeed, Hirsch insists that his band makes typically Parisian music, “a new kind of folk music, mixing African music with other music”.

Aside from Afrobeat, Paris’s electro scene is also growing, with DJs and producers more informed and better equipped to authentically interpret the ancient future. Styles such as Afro house, tribal house and ancestral, previously underground, are now reaching new generations across the globe. Moreover, Africa was the focus of this year’s biggest international music conference, Midem, in Cannes, in June. That affirmed the influence of African music on the international scene today. As Hugh Masekela is reputed to have said: “I’ve got to where I am in life not because of something I brought to the world but through something I found – the wealth of African culture.”