Diaspora-driven development

by Adams Bodomo

The African diaspora is a major source of foreign income — so large that it now outstrips foreign aid sent by western donors. Nearly 140 million Africans live abroad. The money they send back home, remittances, is worth far more — in value and usefulness — than the development donations sent by western financial institutions.

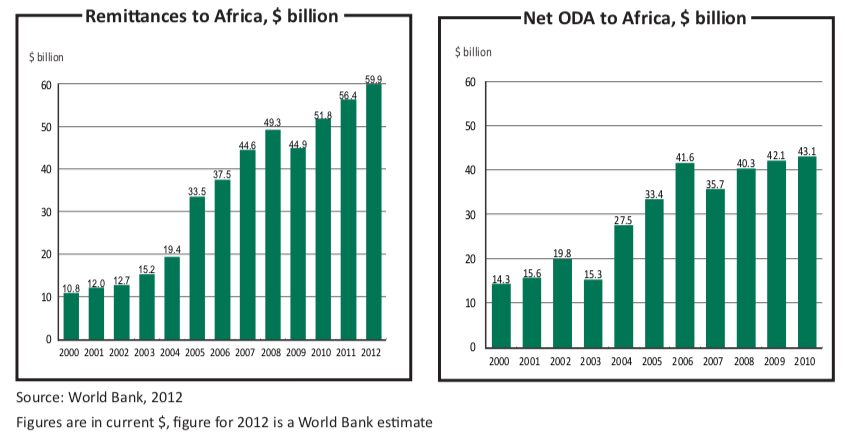

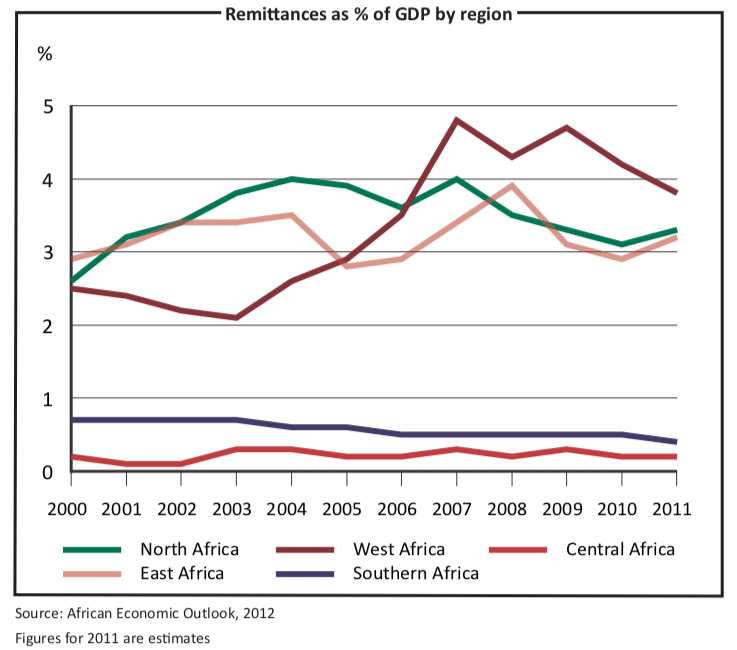

The exact amount of these remittances is unknown because not all of it is sent through official banking channels. But the official volume to the continent has gradually increased over the years, from $11 billion in 2000 to $60 billion in 2012, according to the World Bank. As a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP), remittances in Africa range from next-to-nothing to almost 5%.

Worldwide remittances to developing countries were $351 billion in 2011, far exceeding the $129 billion in official development assistance (ODA), according to the World Bank.

The remittances paid by Africans living abroad also rival official aid to the continent. Total diaspora contributions to Africa in 2010 stood at $51.8 billion compared to the roughly $43 billion in ODA, according to the latest figures from the World Bank.

The payments are bound to grow even higher because new diasporas are emerging in economically fast-developing areas of the world. Currently, more than 70% of the remittances that flow to sub-Saharan Africa are from the West. But this pattern may change because of the economic downturn in many of these countries. Instead, a growing percentage of remittances will come from new African diasporas in places like Brazil, China, India and Russia.

Figures obtained from interviewing about 1,000 African diaspora members in China indicate that Africans send home anywhere from $1,600 to $16,000 per person annually. About half a million Africans live in China. If all were to send money back home, it could add up to anywhere between $800 million and $8 billion a year (This does not include the value of the merchandise bought in China and sold in Africa, which is not considered a remittance but nonetheless is a large contribution to trade from diaspora Africans).

Africans living abroad send money back home through wire transfers that can be tracked. But they also send money unofficially through parcels in the mail or deliver it personally on visits to the family. Up to 75% of remittances sent to Africa arrive through informal channels, according to African Development Bank estimates, suggesting the total amount is up to four times higher than official sums.

Not only are diaspora remittances more substantial than recorded, but they are also more beneficial than foreign aid. Africans living abroad send money home on a regular basis directly to family or friends, who can judge their needs better than the government. These monies go directly towards paying school fees, building houses and growing businesses.

Of course, sometimes families mis-spend their remittances, but this waste is nothing compared to the misappropriations and legendary inefficiencies in the foreign aid industry.

In her book Dead Aid, Dambisa Moyo lists myriad inefficiencies related to foreign aid and exposes the magnitude of official corruption involved in its management. In 2004, experts argued before the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations that roughly $100 billion of World Bank funds spent on development had been lost to corruption, she reported.

Remittances are more efficient than foreign aid because they come without conditions, for the most part. They are gifts of love to family members meant to bring about the development of the family — and hence the nation.

Foreign aid funds, on the other hand, are not free gifts. As with most bank loans, strings are attached. Donor institutions, especially, impose conditions such as structural adjustment programmes, public sector deregulation and privatisation. Sometimes they even demand the overhaul of the country’s political system before providing funds. A case in point is British Prime Minister David Cameron’s recent threat to withhold aid from Uganda and other countries in which homosexuality is illegal.

Some recipient governments and their citizens view these demands as a neo-colonial tool to influence or control their nation’s socio-economic and political development. In many cases there is little evidence that conditions on aid have led to marked improvements in recipient countries’ economies, mostly because of corruption and inefficiency.

But remittances reaching Africa could be even greater. Exorbitant transaction costs, compounded by the nature of remittances (mostly small amounts sent frequently) gobble up a large part of the money sent to Africa. On average, almost 9% of global remittances are lost to banking fees. Africa is the worst hit, losing about 12%, according to the World Bank. So, in 2012, of the $60 billion sent by exiled Africans about $7 billion never made it into their relatives’ accounts.

Given the clear advantages of remittances over foreign aid funds and the large amounts they represent, it is disappointing that African governments have not implemented more robust policies to attract remittances.

One way would be to involve diaspora Africans in their country’s political systems by allowing them to vote from abroad. Another idea, already implemented very successfully by Israel, India and most recently Ethiopia, are diaspora bonds, a debt security issued by a country to its own diaspora to tap into their assets.

Giving African migrants a greater say in the economic and political governance of their countries could foster greater investor confidence.