Illegal and unreported fishing threatens West Africa’s seas

by Jennifer Lazuta

Large foreign trawlers are sweeping West Africa’s seabed, undermining the environment, reducing fish stock and destroying the livelihoods of artisanal fishermen. Issa Diene, 39, is one of thousands of Senegalese fishermen who face tough times in competing with the giant commercial boats. For the past 10 years, he has risen before dawn and set out in his 30-foot wooden pirogue to catch fish off the coast of Dakar, Senegal’s capital. A few hours later he would return to sell his catch at the midday fish market. But recently, poor catches have forced him to fish in the evenings as well, or else spend all day at sea.

“I used to bring in between 15,000 [African Financial Community (CFA)] francs and 20,000 CFA francs ($30–$40) each day,” Diene said. “Then the big boats started coming in and taking all our fish. Now, I am lucky if I catch 5,000 CFA francs ($10) a day.”

Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing is “a big problem in Senegal”, said Cheikh Sarr, director of Senegal’s Ministry of Fisheries and Maritime Affairs. “Large fishing vessels often enter our waters and scoop up all the fish. Sometimes they enter into protected zones. They don’t respect the regulations. Our natural resources are being destroyed. The fish are disappearing. It is hurting our fishermen and ruining our economy.”

IUU fishing can range from vessels fishing with no licence at all, to licensed boats entering into foreign, domestic or international waters and then disobeying the rules. They may catch more than is allowed by law, or scoop up protected species, or fail to report their entire catch, or use illegal or environmentally unsustainable fishing gear, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

It is impossible to know just how much IUU fishing takes place, as many wrongdoers are never caught. Most experts, such as the Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), a British-based campaign group, estimate that between 11 million and 26 million tonnes of fish are caught illegally worldwide each year. This equates to an annual loss to legal fishing operations of up to $23 billion.

The highest level of IUU fishing occurs in West African waters, where up to 40% of total catches are illegal, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts’s project to end illegal fishing. The worst offending vessels in the region come mostly from China, South Korea and Eastern Europe, according to the EJF.

Between 300,000 and 560,000 tonnes of fish are caught illegally off the Senegalese coast each year, according to the FAO. This represents an annual loss to the Senegalese economy of around $300m, according to environmental group Greenpeace.

Some experts say these numbers might actually be much higher. For the first time, a team of researchers led by Daniel Pauly, a fisheries scientist at the University of British Columbia, has examined underreporting by Chinese fishing vessels. This study, released in March 2013, found that an estimated 4.6 million tonnes of fish were caught illegally worldwide each year between 2000 and 2011. Nearly three million of those tonnes — worth more than $7 billion—came from West African waters.

The region’s artisanal fishermen like Diene cannot compete with the large, foreign vessels that come into their waters. Their financial losses are devastating. One industrial trawler can scoop up more fish in a day than 50 local small fishing boats can catch in a year, Greenpeace reported.

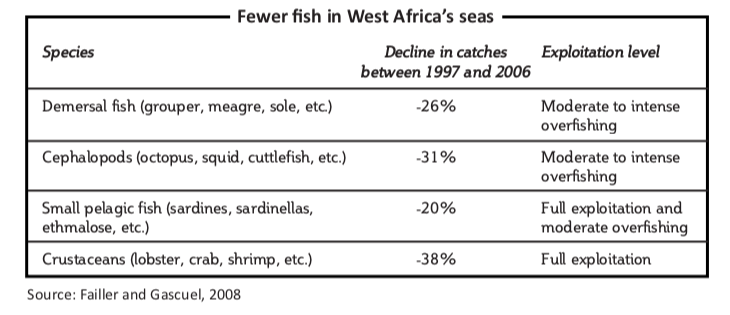

As fish stocks continue to decline off West Africa’s coast, mostly because of overfishing, Diene and many other local fishermen have been forced to look for their catches on the high seas, where they risk being attacked by the trawler operators, or else in protected zones closer to home, which further threatens fish stocks.

“Truly, the fishermen are tired,” Diene said. “Each time, you must go farther and farther to the high seas. It’s dangerous. And all that gas; the costs are expensive. Then you come back, only to find you earned nothing and you are scared,” he said.

Industrial foreign trawlers also venture into local waters and reduce fish stocks, forcing local fishermen to catch smaller, younger fish that previously would have been left behind to reach adulthood, said Steve Trent, the EJF’s executive director.

“What the decrease in the individual fish size means is that they are catching younger fish. And very often, they’re catching fish that should be allowed to mature, that play a fundamental role in sustaining the fisheries and the general ecological balance,” Trent added.

Not only is this damaging the ocean’s environmental health, but seafood prices in local markets are rising as the size of the catch and the fish diminish. Experts say this is a worrying trend in a country where more than three-quarters of the population rely on fish as their main source of protein.

“Many of these coastal communities don’t grow anything,” Trent said. “They don’t have access to other food resources or, in particular, animal protein. So if they are getting a decreased catch, or if they can’t afford the fish, they are quite literally going hungry at times. Their food security is being threatened,” he said.

Illegal fishing is also harming the marine environment. The EJF reports that nearly 90% of the large industrial vessels drag the seabed with heavy trawl equipment to maximise their catch. This damages the ocean floor and destroys marine habitats. Many boats also continue to use large, monofilament nets, which entrap or gather other, often unwanted, marine species, which are then discarded.

Fortunately, the authorities in Senegal are reacting to the IUU fishing problems.

“What we saw [in previous years] was that there was a complete denial of illegal fishing,” said Dyhia Belhabib, the lead researcher on West African Fisheries for the Sea Around Us Project, a scientific collaboration between Pew and the University of British Columbia.

“But now, due to a change of government and the monitoring agencies, the authorities are saying that now, yes, they are really concerned. They are looking at the reports and they are looking at the most recent numbers, and they are making recommendations to the ministries.”

One of the first big changes came in 2012 when Senegal’s current president, Macky Sall, came into office and made good on campaign promises to combat illegal fishing. The government revoked the fishing licences of 29 industrial trawlers that had previously been operating in Senegalese waters.

“This was a decision of resource management that was made to reduce the number of fish being taken from our waters,” said Sarr, the fisheries director. “It was made in light of the concern over the rarity of resources, and it was a decision that was made to allow the fish a chance to regenerate.”

While Sarr, local fishermen and environmental groups say that cancelling these licences has helped with the problem of overfishing, it has not necessarily helped with the problem of illegal fishing.

“Revoking these licences has been helpful in the general sense,” Sarr said. “But the reality is, whether or not a boat is authorised to enter our waters, if they decide to engage in IUU [fishing], they will come,” he said. “And often, we have very little power to stop them.”

Senegal has a legal structure to combat IUU fishing. Its maritime code defines legal fishing zones, dictates what species of fish can be caught and controls the licences that are given. It also outlines penalties for breaking these laws and punishing offenders. But a lack of resources and money make it difficult for Senegalese authorities to enforce this code. “Senegal just does not have the capacity to go after these vessels,” Belhabib said, “especially because they [the industrial trawlers] usually operate far from the coast. Senegal’s patrol vessels just aren’t big enough to go after them.”

Experts say that the government needs to increase the number of naval patrols and days spent monitoring at sea, engage in aerial patrolling, raise the number of on-board observers (to ensure that only authorised species are caught) and enforce the use of vessel monitoring systems, a Global Positioning System-like tool that tracks the movement of boats.

West African authorities also need to increase cooperation with one another. This could include creating a single database to monitor numbered vessels and creating uniform laws and penalties for IUU fishing offenders.

Senegal is a member of the Sub-regional Fisheries Commission, an intergovernmental organisation of seven West African countries that was created in 1985 for transboundary surveillance and enforcement.

“The commission has been good, in theory,” Sarr said. “For example, when a boat is fishing illegally in one country and then starts to flee [into the waters of another country], there is an accord that allows the navy to follow it and to ask for assistance. So this cooperation is quite important,” he said. “But many member countries still lack the means to fully participate.”

Sarr and other experts also emphasise the importance of government cooperation with destination countries, such as Europe, Asia and the United States. When vessels return to their ports from foreign waters, for example, authorities must have a system to determine whether the unloaded catch was caught legally or not.

Increasing fines might deter IUU fishing off West Africa’s coast and ease some the official burden of arresting them, according to Trent and others. Currently, pirate vessels scoop up large amounts of fish, with little risk of being caught or punished. According to Senegal’s maritime fishing code, any foreign ship found to be fishing without authorisation in Senegalese waters is subject to a fine of up to $400,000 — if they are caught. But if fines were raised high enough, the vessels might not even attempt to fish illegally in the first place.

“If you look at the value of a reefer carrying a hull full of fish, you are talking millions of dollars,” said Trent. “Governments need to make the penalties high enough so that these pirate ships just don’t factor them into their operating costs and almost don’t care.”

Sarr said that the fishing ministry is acting on these recommendations and revising the current code, which has not been updated since 1998. “A stronger penal code will help us fight IUU [fishing], but it won’t be easy,” Sarr admitted. “The surveillance technology is improving, but we still lack the resources and the manpower. And just as the destruction process [of our fisheries] took time,” he said, “the process of restoration will also take time.”