The very word sounds scary, but “fracking” holds tremendous promise for Algeria, Libya, Morocco and South Africa, which possess large reserves of natural gas in deep shale rock layers. Environmentalists warn that it will poison the water and ruin the landscape. Some even call it “worse than coal”. Do they exaggerate or are the environmental risks small and the economic benefits too great to sacrifice? Ivo Vegter examines the research and cracks apart the opposition’s claims.

Natural gas is projected to be the fastest-growing component of world energy consumption, more than doubling between 1997 and 2020, according to the United States (US) Energy Information Administration (EIA). The International Energy Agency, a rich-world energy club, predicts 25% growth in gas production in Africa over the next five years. In the US, natural gas production has risen more than twelve-fold between 2000 and 2010, sparking a boom in drilling activity that supports 150,000 direct jobs and perhaps as many as 600,000 in total, reports research firm IHS Global Insight.

The US has become the poster child for the changing face of petroleum extraction. Oil and conventional gas are seen as mature industries, but so-called unconventional gas is the game-changer. Conventional gas typically collects in porous pockets underground, from which it is relatively easy to extract. “Unconventional” gas—including coal bed methane, tight sand formations and shale gas—is contained in impermeable rocks, usually at depths of between two and five kilometres. Although unconventional gas is much more abundant than conventional gas, traditional vertical drilling cannot reach enough of it to create economically viable wells.

Today, it has become possible to exploit unconventional gas deposits thanks to a combination of high energy prices and innovative techniques. Horizontal drilling was pioneered in the 1980s and has been thoroughly tested in offshore oil drilling. Another technique, which by some accounts dates back to the 19th century and has been used in over a million wells since the 1940, requires using hydraulic pressure to fracture impermeable rock and is better known as “fracking”.

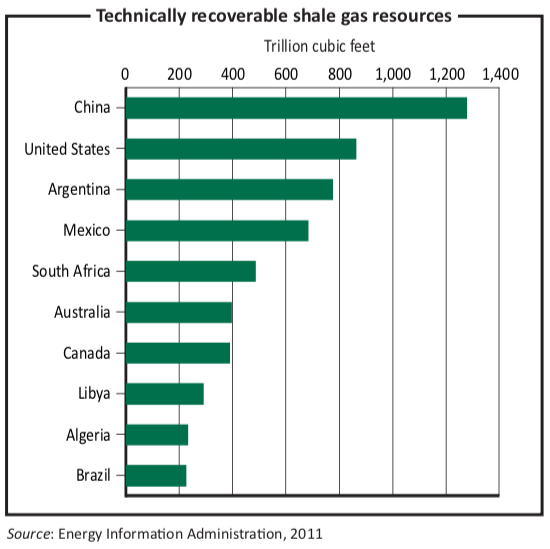

Africa is well placed to profit from the gas boom. The West African region centred on Nigeria has both conventional and unconventional reserves, the latter in the form of coal-bed methane and tight sand formations. New conventional gas discoveries in Mozambique, Tanzania and off the coast of Angola hold a great deal of promise. Unconventional gas exists in the deep shale of the Karoo Basin in South Africa, with an estimated recoverable reserve of 485 trillion cubic feet (tcf), the fifth largest in the world. Several shale gas basins also span North Africa from Morocco to Libya, adding up to a very sizeable 557 tcf.

By comparison, the Mossgas project in South Africa, with its associated gas- to-liquids plant, was given the go-ahead on the basis of a 1 tcf recoverable reserve of conventional gas.

The numbers sound impressive, but should be interpreted with caution. Estimates of the quantities of unconventional gas are based on geology rather than exploration. The oil and gas industry is keen to discover the true extent of the potential gas wealth, but exploration could take a decade before full production can commence. This makes economic predictions difficult.

The best forecast in South Africa, by the late Tony Twine for Econometrix in January 2012, uses standard techniques for estimating the economic effects of shale gas production. Based on several conservative scenarios, it predicts maximum direct and indirect employment of 350,000 to 850,000 people while contributing $250m to $625m to the broader economy. Besides these benefits, an abundant domestic supply of natural gas could be used to produce cleaner, cheaper electricity and automotive fuel.

In South Africa, green lobbyists, the highly visible Treasure the Karoo Action Group, lead the charge against exploration. They cite anecdotal evidence that fracking can cause groundwater pollution as a key concern. Evidence of this in the US, where many production wells exist, is rare. Groundwater deposits are typically found at a much shallower depth than shale gas and are separated from them by layers of impermeable rock. There are comparatively few reports of groundwater pollution and many of the more convincing cases could not be blamed on shale gas drilling or were found not to be serious at all. Propaganda images of flammable tap water or methane bubbling from streambeds were shown to result from gas naturally occurring in water wells. In many cases, this phenomenon predated shale gas drilling.

A widely-publicised American study by Duke University researchers in May 2011, which set out to find well water pollution caused by shale gas drilling, proved to be significantly flawed. The researchers could not find evidence of the tell-tale chemicals used by the industry.

Isolated cases of chemical contamination in anti-fracking hot spots such as Dimock, Pennsylvania, and Pavillion, Wyoming, have proven to be exaggerated. The pollution risk appears to be largely confined to above-ground handling of fracturing fluids and wastewater. Even then, serious incidents are few and far between.

Another concern is the amount of water used during the hydraulic fracturing process. Even in a dry region such as Texas, extensive fracking consumes only 1.7% of the area’s water supply, comparable to the water requirement of golf courses or coal- fired electricity generation.

In South Africa, 82.5% of the available water supply is used for irrigation and forestry, according to the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry. Drilling companies in South Africa have already publicly committed not to compete with local farmers and residents for water. Several alternatives exist to the use of existing freshwater supplies. The industry trend has been to improve its methods to recycle wastewater and use less water overall.

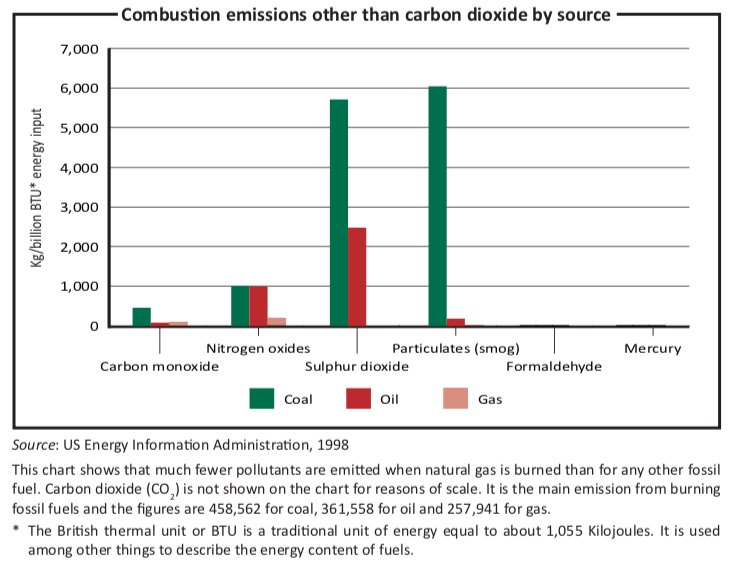

In January 2012, Robert Howarth, Renee Santoro and Anthony Ingraffea of Cornell University claimed that “fugitive” emissions of methane during production nullify the benefit of burning shale gas instead of coal or oil. Like the Duke University study, this one has been widely discredited, including by Lawrence Cathles, a scientist at Cornell also. Even a green lobby group, the Clean Air Task Force, which opposes all fossil fuels including natural gas, declared: “This paper is selective in its use of some very questionable data and too readily ignores or dismisses available data that would change its conclusions.”

Despite this discredited research, environmental lobby groups continue to rely on such studies to make their case. More credible research fails to support their strident opposition to all shale gas drilling.

Some of the danger flags such as the presence, composition and movement of underground water in the prospective drilling regions will require further research. On the evidence available today, however, the warnings of environmental lobby groups that are so popular in the press seem to be wildly overblown.

Largely ignored by the media is another South African interest group representing local workers, the unemployed, small-scale farmers, church groups and youth organisations. The Karoo Shale Gas Community Forum is much less well funded and is not run by middle-class environmentalists and rich landowners upset that their mineral rights no longer belong to them. Unlike the environmentalists, its position does not make for sensationalist headlines. It asks the government to ensure safety standards and impose obligations on drilling companies should accidental spills or contamination occur. It does not share the idealism of leaving natural resources untouched at the cost of sacrificing the potentially large benefits of shale gas: jobs, socio-economic development, tax revenue, energy security, carbon emissions and electricity supply.

Their position is more sensible: conduct the necessary research; require environmental impact assessments and environmental management plans; and be sure to hold gas-drilling companies responsible for any unintended harm that their operation might cause. Having established that the risks are indeed small and manageable, the bigger responsibility is to promote an industrial ecosystem that can thrive on natural gas. This will involve infrastructure such as pipelines to supply domestic markets and near neighbours, and gas-to-liquids facilities to ship gas to markets like Asia and Europe, where prices are much more attractive than in North America.

Governments should also devise policy to minimise the risk of the so-called “resource curse” (see Issue 3 of Africa in Fact). Often, countries with a single large natural resource suffer low economic performance for a variety of reasons, including high currency exchange rates that depress other sectors, investment over-concentration and commodities volatility. The most serious cause, however, is corrupt, inefficient or crony-capitalist governments. This is a far greater risk than environmental harm, especially in countries where the government owns the mineral rights and receives both the royalties and tax revenues associated with resource exploitation. The cautionary tale of Nigeria is well known, but is not unique in casting a spotlight on resource revenue management and regulatory transparency.

The benefits of shale gas resources can filter throughout the economy and make a real difference to industrial competitiveness, energy prices, export revenue and the alleviation of poverty and unemployment, but only if governments are responsible stewards of their countries’ natural resources.