Sowetan: a case study

The role of organisational culture in journalism can be seen in the rise and decline of South Africa’s iconic newspaper the Sowetan

What is it to be an “African journalist”? Working in African countries can mean operating in challenging conditions, with limited resources and sometimes restrictive political environments. African media have been shaped by their histories – as colonial, revolutionary or post-independence presses, as state broadcasters, as community or development projects. Still, despite its different origins and contexts, African journalism is often seen as a simple variant of the professional journalism of the West, with reporters sharing the same values and practice. The Worlds of Journalism project, for example, a study of more than 1,800 journalists across 22 countries, which was founded in 2010 and which publishes studies of global journalism as well as case studies of journalism in particular countries, has not found significant differences in journalistic cultures in African nations.

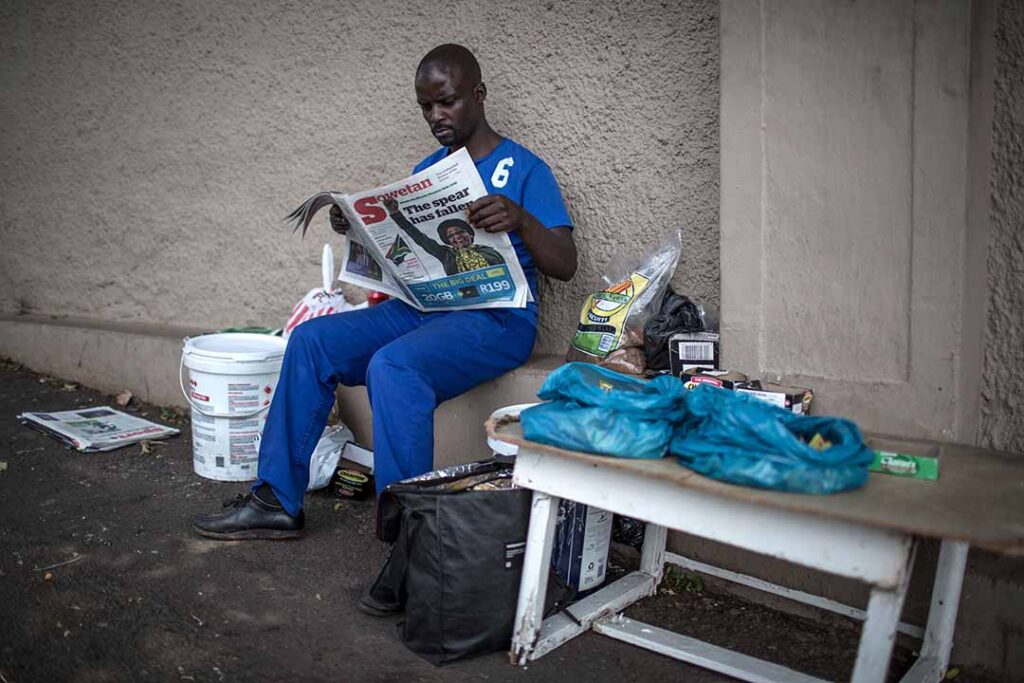

In fact, there are more likely to be differences between journalists who work in different mediums (broadcast or print) than variances across ethnicity and nation. Many studies show that there is a sense of “professional identity” among African journalists, but what that identity is, and how it is put into practice, is still open to question. In the mix of factors that shapes journalistic identity, organisational culture is hugely important. Although journalism newsrooms may have similar production processes and routines, individual organisations are shaped by the particular contexts they operate in, and by their internal dynamics, so they develop cultures specific to their workplaces. Journalists learn their trade in their newsrooms, where they are socialised into certain values and practices. The organisation is the matrix through which their journalism is learned and expressed – and shapes the kind of media that is produced, its success and failure. The role of organisational culture can be seen in the rise and fall of Sowetan, a Johannesburg newspaper established in 1981, originally as a community free sheet for the residents of Soweto township.

In the early 1990s it was the most-read daily in South Africa and had enormous influence in the period of transition from apartheid to democracy. Its readers were largely urban black South Africans living in township areas. In its heyday, it became a national newspaper, circulating to towns and rural areas across the land. It is still operating in Johannesburg today, with a much-reduced readership. In the apartheid era, Sowetan was part of a collection of black newspapers owned by white media companies – its editors had to fight management for the autonomy to produce a newspaper that met the political aspirations of its readers. Most Sowetan journalists had worked for predecessor newspapers, the World and the Post, which had been banned by the apartheid state. They were activists in their newsroom and outside it – “cadres with a pen”, as former editor Len Maseko has called them. The conscientisation had come with the rise of Black Consciousness (BC) in the 1970s, when journalists were confronted by activists with the question: are you a journalist first or black first?

By the 1980s, many journalists were members of political movements, and most belonged to the BC union, the Media Workers Association of South Africa (Mwasa). They organised strikes and protests, and experienced harassment, detention and banning. In the late 1980s, under the leadership of editor Aggrey Klaaste, Sowetan launched a community-oriented programme centred on the theme of nation-building; he refocused the newspaper around this philosophy. The newspaper’s vision of a nation-building community, with a leading role for black South Africans as citizens in a greater society, brought it readers and gave a competitive advantage to its owners, the Argus Printing and Publishing Company. The newspaper continued to promote its vision into the 1990s, which made it a player in broader discussions about the new democracy. During the tumult of societal transition, Sowetan experienced a period of organisational stability. The Argus partnered with a new black business as 50/50 owners and kept a hand in the management side of the newspaper.

Circulation remained relatively steady during the 1990s at around 210,000 – the biggest daily in South Africa. Klaaste moved to an overarching role as editor-in-chief so that he could be more involved in the many nation-building projects the newspaper ran, and handed day-to-day editorial management to others. In the 2000s, New Africa Investments Limited (Nail), a black empowerment company close to the ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC), took full control of the paper. The new owners decided to refocus Sowetan to serve more affluent readers. The staff resisted the change, and readers deserted the newspaper in droves. Circulation went from almost 200,000 in 2001 to 118,000 in 2004. In two years, the newspaper lost almost half its readers and Nail put Sowetan up for sale. Sowetan was bought by Johnnic Communications (Johncom), and the company immediately began plans to reposition the publication. Sowetan’s loss of readers had been accompanied by the meteoric rise in circulation for a new tabloid, the Sun, which dealt in crime, witchcraft and scandal.

Johncom planned to go tabloid with Sowetan – to inject more upbeat, lifestyle and celebrity stories, while still keeping some advice and self-help content. Nation building, the market research seemed to show, was associated with the old “freedom-fighting” mentality, whereas the changing readership wanted “funky”, “sexy” copy that reflected the aspirations of individual readers. Many of the journalists resisted. They saw the relaunch as a challenge to Sowetan’s historical responsibility to a black nation-building public, while the incoming executives felt the commercial viability of the paper was at stake. But the conflict after the takeover was not simply a dispute about journalism – it seemed to encompass a range of other workplace issues. Management theory recognises this as organisational culture, which is resistant to change. Edgar Schein, in his book Organizational Culture and Leadership (2010 and later editions), writes that culture is shaped by contextual factors and by the leadership of an organisation, which develops values and practices that become “deep assumptions”.

These continue to operate in an organisation after conditions change, being passed on to new members. Such assumptions can be unexpressed, but shape the behaviour and values of members of the group. In the case of Sowetan, journalistic identity historically had coalesced around activism against apartheid and, under Klaaste, around nation-building. This was not simply opposing apartheid; it also meant sharing in the conditions of the readers through living in the township, through dialogue, and through representing them in a society that oppressed them. The long-time “Sowetans” identified strongly with township culture, a “macro-culture” outside the organisation. Expressing township culture through food, drink, ubuntu practices – conceived of as helping each other in everyday working life – became markers of authenticity. The Johncom managers needed to demonstrate their acceptance of this culture. You could never be an insider unless you ate township street food, drank with the guys at the end of the week, and joined the union, Mwasa. On the other hand, many of the incoming managers, who were perceived as “outsiders”, found the environment “unprofessional”.

The notion of being “professional”, for the newcomers, had to do with having reporting and writing skills – accuracy, well-researched stories, and meeting deadlines. It also meant having the “right attitude”. In most newsrooms, there would be consequences for breaches of professional codes. For Sowetan reporters, the focus was on representing the community. Journalists took pride in being in a newsroom with deep roots in the townships. The work of “building up” the community through reporting and projects was more important than the cold professionalism of the corporate owners, which seemed to lack ubuntu. A dynamic of mistrusting managers went back to the early days of Sowetan. The Argus Company established black readership newspapers for commercial reasons, but invested little by way of resources. Sowetan had run-down offices in an industrial area on the outskirts of the township and received the broken down chairs and second-hand computers from other newsrooms. The hostility towards management had deep roots in a resentment of exploitation. Given this long-held assumption, the proposal by Johncom to reposition as a tabloid was seen as an attempt by a white company to benefit commercially at the expense of the black community.

Editorial staff thus held up the implementation of the redesign. Media expert John Soloski has argued that the unpredictability of the news environment means that journalists have considerable autonomy to make decisions in reporting and processing news, which gives them the power to sabotage the process. In Sowetan, resistance took the form of withdrawing cooperation in the production processes of the newspaper, not attending editorial meetings and actively arguing against the repositioning. Eventually, the newspaper settled into a compromise position, including tabloid elements in the redesign, but retaining some of the old community building elements. The circulation stabilised, and Sowetan continued to attract advertising. It now operates out of offices in Johannesburg city, rather than Soweto, and faces the same uncertainties as other South African newspapers in a changing business environment. The story of the Sowetan supports the idea that there is no universal journalism culture. The attachment of Sowetan journalists to their particular values and practice suggests that forms of journalism evolve in certain contexts to diverge from the professional Anglo-American modes.

Journalists working in different contexts may refer to similar values – such as the public interest and news – but they will also interpret them differently in practice. To understand journalistic identity in Africa, it is important to understand that every media organisation is a powerful space in which specific journalism cultures are forged.