Zimbabwe: asleep at the wheel

Trade unions provide yet another reason for Mr Mugabe to rest easy at night

By Ray Ndlovu

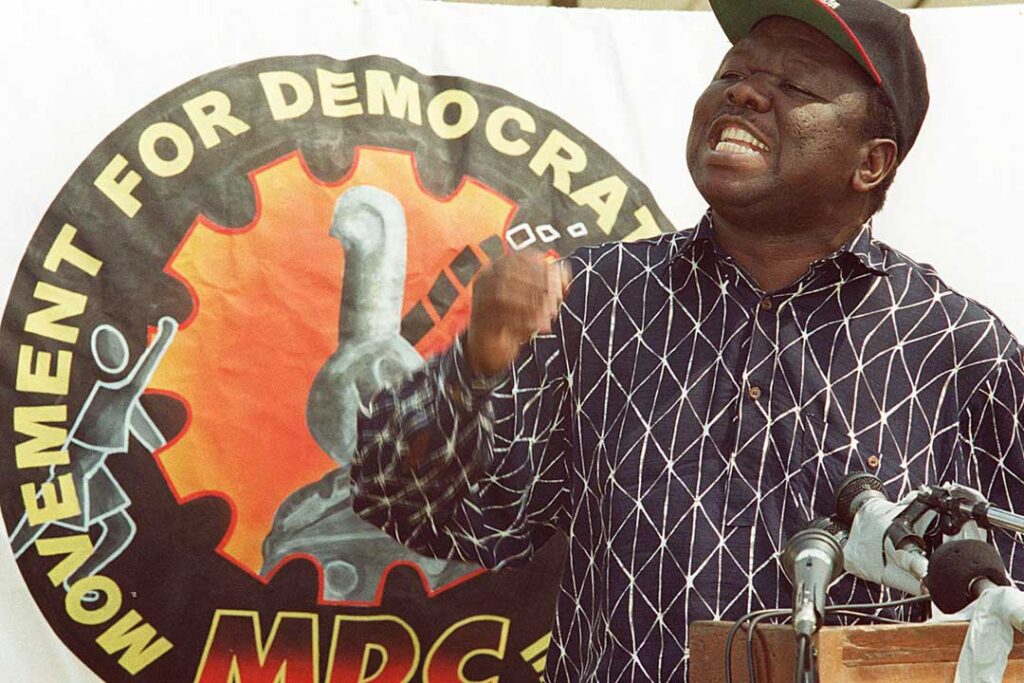

Back in the 1990s, the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) was a fierce opponent of President Robert Mugabe. It drove the rise of resistance politics in the country and gave birth to the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), Zimbabwe’s largest opposition party. Unions were at the frontline of political activism in Zimbabwe when Morgan Tsvangirai headed the federation and went on to found the MDC in September 1999. He has remained a thorn in Mr Mugabe’s side ever since. But unlike Mr Mugabe, who marked 35 years in power this April, unions are weaker than ever and the opposition is deeply divided. This could keep Mr Mugabe’s party, the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (Zanu- PF), in power for many more years to come. Union muscle, like its close ally, the MDC, is weakening. According to research released in May, 63% of Zimbabweans trust Mr Mugabe more than the opposition. The MDC’s popularity has dropped from 57% in 2008 to 31% in 2012, while Zanu-PF’s has grown from 10% to 31% in the same period, according to the report by South African-based think-tank Afrobarometer and the Zimbabwebased Mass Public Opinion Institute.

“Opposition political parties are least trusted,” reads the survey, a point that is illustrated by the MDC’s electoral defeat to Zanu-PF in 2013. Even in the absence of the ruling party, the opposition would still not have popular support, said Alex Magaisa, a former legal adviser to Mr Tsvangirai. “Is it that people see Zanu-PF as a better devil?” he asked. “Is it that the fights and splits in the opposition have reduced levels of confidence in the opposition?” The MDC has splintered into several incarnations since it first split in 2005. Now there are three: MDC-T headed by Mr Tsvangirai; the MDC; and the MDC Renewal Team, formed last year. These divisions and a downward spiralling economy have crippled organised labour. Trade union militancy began in the 1990s after the government adopted an IMF structural adjustment programme, removed subsidies and liberalised prices. The unemployment rate in the 1990’s averaged 7%, according to the Reserve Bank, in contrast to the current 90% estimated by economists and trade unions in media reports. (Information from Zimbabwe remains highly unreliable, suffering from poor primary research, disputed employment definitions and difficulties measuring the informal sector.)

“The number of members in trade unions and the workforce was much bigger than is the case today,” said John Robertson, an economist. “The economy was not so hostile and business was protected by government regulation, which was seen to be more supportive of employers. Today unions find themselves on the receiving end; job creation has fallen sharply, membership has fallen and income, which it relies on for survival, has dwindled.” Company closures and retrenchments have become the new norm and have been widely reported by local newspapers. In the first quarter of 2015, at least 67 companies closed down and 1,000 workers were laid off , according to the Retrenchment Board, a government agency. Productivity in the manufacturing sector will continue to diminish, said Chiratidzo Mabuwa, deputy minister of industry and commerce, at a trade fair in April. Industry output “is expected to operate at 30% by the end of 2015, down from 36% last year”, she said, a rare admission from the government that the economy will worsen. The labour movement is in the doldrums because “most people are in informal employment,” said Vince Musewe, an economist based in Harare.

Formal employees “are owed thousands of dollars in unpaid salaries and are unwilling to engage in strikes which may be seen as illegal,” he added. “The resolve of many then is to just hold back and not take part in labour-backed processes.” The downturn has been devastating for ZCTU, which had 400,000 members at its peak in 1995. Its nationwide strikes and street demonstrations demanding higher wages and better working conditions often brought business to a standstill and involved running battles with police. But in the last decade, economic stagnation and a growing informal economy have seen ZCTU membership fall by 60% to 160,000 nationwide, Japhet Moyo, the ZCTU secretary general told Africa in Fact. “Unions can only thrive where there are formal jobs,” he said. “The challenge for ZCTU is that it now has to organise people who are unemployed. When the [employment] numbers dwindle, that puts constraints on union operations, and when members are few, the scope of our influence is affected.” Compounding the economic decline weakening unions is the government’s reputation for beating or arresting dissenters, said Vivid Gwede, a political commentator.

“This means that with the reduced worker numbers, the state has a reduced challenge on its hands, and it has constantly thwarted efforts for freedom of expression from the remaining contingent of workers,” he added. “The reality is that due to the state’s intolerant approach, it is hard, though not entirely impossible, for anyone to mobilise for any cause, including working class interests.” In addition to a downward spiralling economy, the ZCTU is also weakened by internal leadership wrangles and emerging factions. When it calls out its troops, it cannot count on their arrival. ZCTU organised a nationwide series of demonstrations in April to protest the government’s failure to fix the economy and create 2.2 million jobs, a promise Mr Mugabe made in the 2013 election campaign. But few people turned out, in what many see as a sign of entrenched discouragement. In Bulawayo, Zimbabwe’s second largest city, only 200 people took part in the demonstrations, while in Harare, the capital, only “a handful”, far fewer than the anticipated 1,000, showed up, admitted a union official. The failure of the ZCTU demonstrations was a result of inherent weaknesses in the organisation itself, explained Sifiso Ndlovu, chief executive of the Zimbabwe Teachers’ Association (Zimta), a ZCTU affiliate with 40,000 members.

The federation “meanders between politics and labour”, he said. “Its attachment in particular to the MDC led by Mr Tsvangirai is compromising the work of trade unions and workers, and that has been its undoing. Other organisations that have labour interests are left doubtful of their sincerity.” But industrial action can sometimes still be effective, Mr Ndlovu admitted. After pressure from Zimta and other civil servant unions, the government retracted a decision it had made in April to scrap civil servant bonuses, a rare labour triumph. While this victory may signal rising militancy within some ZCTU affiliates which have their eyes on organising the country’s 550,000 civil servants, the labour federation is fading away. A fragmented opposition on one side and an economy in tailspin on the other darkens its demise and brightens the chances that Mr Mugabe’s Zanu-PF will continue to rule.