Chinese labour in Africa

They are a manifestation of the globalisation that has transformed the world’s economies

By Richard Poplak

What exactly are we referring to when we talk about Chinese labour in Africa? Are we discussing the Asian men in overalls standing on the side of freshly paved roads in the continent’s remotest crannies? Are we musing about the men and women who sell cigarettes and laundry soap to villagers in those same forgotten places? Or are we talking about the “old Chinese” executives who run logistics companies or restaurants or nail bars in South Africa’s big cities? The category is too broad to be considered as a piece, but nonetheless too many editorials and op-eds insist on jamming all Chinese working in Africa into the same taxonomic box. This poses an overarching question: are the 1m or so Chinese nationals (according to an estimate by The Economist) who live and work on the African continent a neo-colonialist scourge that matches, if not outstrips, the one that preceded it? Or are they flying solo? To arrive at an answer, we need to properly understand the sweep of Chinese engagement in Africa and the critical role labour plays. First, it is important to acknowledge that this is not the first time Chinese nationals have come to Africa to work in sizeable numbers.

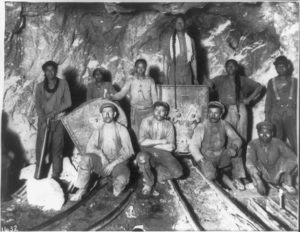

In 1891, poverty-stricken Cantonese started making their way to the bottom of Africa to take advantage of Johannesburg’s gold boom. Thirteen years later, addressing a severe labour shortage in the Transvaal, the South African government resolved to “import” 34,000 indentured labourers to work the mines and railroads. The Xiamen Overseas Chinese Museum, located on the southern coast, displays images of thousands of Fujianese being hoarded onto boats bound for Cape Town. It was a forced exodus of terrible proportions, one that still resonates in the Chinese psyche. A year after the first tranche of labourers arrived, 64,000 Chinese were working in South Africa, a cohort so significant that they began driving down the price of labour and causing considerable resentment among the black population. In 1907, following a massive repatriation drive, most of these Chinese had returned home, but many of the earlier Cantonese immigrants remained. They have formed a lasting component of South Africa’s multi-ethnic make-up, and a significant number of the half a million or so Chinese in the country.

But if industrialisation was the impetus for this first Chinese influx, the second great wave has been a result—or rather, a symptom—of globalisation. Over 34m Chinese nationals are living and working abroad, according to the Dr. Shao You-Bao Overseas Chinese Documentation and Research Center at Ohio University. This is equal to Canada’s population. In Fujian and Guangdong provinces, the notion of making a go of it on distant shores is hard-wired into the culture. If there were winners in the Chinese growth sweepstakes (as Deng Xiaoping was said to have said, “some will get rich first”) there were also losers: the two coastal provinces that disgorge most of China’s migrant labourers fall firmly into the latter category. With factories moving north, Fujian and Guangdong were undone by the vicissitudes of the new Chinese order. As ever they had, their people looked afar for opportunity. According to a 2013 report from the South Africa-based Brenthurst Foundation, the Fujianese form nearly 90% of Chinese traders in southern Africa—those who open spaza shops (small informal stores) everywhere from townships to rural villages.

These men and women are the frontline of the Chinese labour phenomenon in Africa. They are an integral part of the communities in which they work, providing groceries and consumer items at costs far lower than local traders. This fact itself has transformed African economies in ways that are often resented by locals. Chinese-made goods, derisively termed “fong-kong” or “zhing-zhong”, may be cheap, but are also perceived as low quality. In South Africa, the “new Chinese” often live with the constant threat of violence. This has spawned an entire subsidiary industry of moving cash from stores or trading outlets to safe houses. And while these traders form the most obvious element of Chinese labour in Africa, they are by no means the most pernicious, at least as far as the African press is concerned. That category belongs to the men who are flown into Africa by Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to build the plethora of infrastructure projects that define this particular era of African development. The popular perception is that these schemes are the result of infrastructure-for-commodities swaps that mortgage the continent’s future for poorly constructed roads—with no upside for Africa’s unemployed.

The reality, of course, is more complicated. As a rule, Chinese SOEs use imported labour, mostly in skilled positions. Sino-African expert Deborah Brautigam, in an attempt to combat the widespread misapprehension that Chinese firms do not hire Africans, has run the numbers in a way that roughly tracks with this writer’s anecdotal experience. “I’ve not yet seen a case of a Chinese company in Africa hiring no local workers at all,” writes Ms Brautigam on her blog. “But the percentage of Chinese and Africans varies widely.” The following examples are taken almost at random: the 2007 Tanzania village water systems project employed 50 Chinese engineers and technicians and 500 local workers. The huge Merowe Dam project in Sudan appeared to have a ratio of one Chinese worker for every ten Sudanese. This ratio inverted precipitously in Angola, where the Luanda Stadium project employed 700 Chinese and 250 Angolans, while the building of the Benguela Railway, between Munhango and Luau, employed 300 Chinese technicians and 300 Angolans at last count in 2010. Overall, when Ms Brautigam’s numbers are calculated, the ratio across the continent works out to around one Chinese worker for every five Africans.

It should be noted, however, that this is an approximation based on notoriously diffident numbers. Chinese SOEs are by nature opaque, and African governments likewise. But the numbers suggest that Chinese mega-projects employ Africans, often in large numbers. And because so much of the Chinese labour is primarily skilled, it gives lie to the evergreen accusation that China uses imported prison labour on its African projects. If 1m Chinese are living on the continent, subject to local laws and cultural mores, what does this mean for the workers themselves? Can they expect labour protection, disability benefits or any social safety nets? The answer is very often “no”. As the Brenthurst report notes, Chinese traders have no contact with Beijing or her ambassadors. More often than not, they are left to fend for themselves. “The Fujianese give me a headache,” Zhong Jinhua, the ranking Chinese diplomat in Africa, explained to this writer. More formal labour with the SOEs is typically subject to Chinese labour regulations, which is famously unprogressive. These workers fall outside of African countries’ laws, a labour sub-category that suggests that dealing with the Chinese means coughing up a small chunk of sovereignty.

Still, it must be emphasised that no two African countries have dealt with Chinese labour the same way. In South Africa it would be politically unviable to have Chinese labourers working on construction projects. In Angola, the government does not care and Chinese workforces routinely undertake Chinese projects. There is absolutely no consistency from nation to nation, and no coherent approach at a multilateral level. It goes without saying that the African Union and Beijing have not tabled any deals or formal agreements. In the final reckoning, 1m Chinese nationals on a continent of 1.1 billion represent a blip. But the relationship between these two entities speaks to massive forces that are typically outside the realm of local understanding. These workers are here because the world’s borders have become vestigial. They are the most visible manifestation of the globalisation that has transformed economies and pushed markets into a vast and ungovernable realm.