A series of solar and wind farms sprouting across the Sahara desert may electrify much of North Africa and even parts of Europe. Christopher Coats examines this massive renewable energy project and its challenges of time, funding and political will.

For the better part of the last century, the economic and political potential of many North African nations has been measured by their ability to exploit the region’s vast energy reserves. Algeria, Egypt and Libya have offered oil and gas fortunes to those willing to look past a volatile political setting. Tunisia and Morocco have provided more modest opportunities as oil and gas transport and refining hubs to the European and North American markets. Governments have profited from the energy sector’s revenues at the cost of needed economic diversity, as seen in the lop-sided dependence on oil and gas in Algeria and Libya.

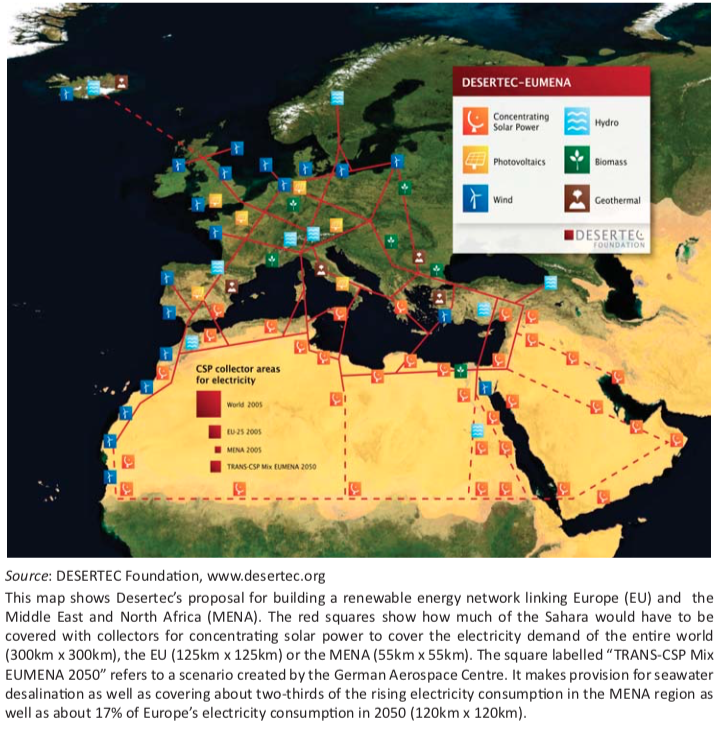

In recent years, however, a growing number of business and political leaders have shown interest in the region’s other abundant natural resource: the Mediterranean’s sunshine and strong winds. Enter the German-led Desertec Industrial Initiative and Foundation: an ambitious plan to create a sprawling grid of large and small-scale solar and wind farms (though mostly large) from Tangiers to Cairo and possibly beyond. Expected to cost up to half a trillion dollars, Desertec has the potential to address the Maghreb’s domestic energy needs while providing an estimated 15% to 20% of European energy requirements by 2050 through a network of underwater cables stretching across the sea.

The solar and wind project is not a complete shift from the regions’s reliance on traditional hydrocarbons, rather a drift towards energy diversification. It has the added potential to earn revenue by exporting excess energy to Europe while boosting local economies through jobs and technical training.

Investors are worried, however, about the region’s political stability. The transitions in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya over the last 20 months have boosted confidence in North Africa’s new political freedoms. Potential green energy investors remain wary, however, and are adopting a wait-and-see approach before committing additional funds.

This resistance is unlikely to affect Libya and Algeria with substantial oil and gas revenue which can be used to support Desertec’s initial efforts. Tunisia, Morocco, and to a lesser degree, Egypt, however, will find it harder to obtain international financing.

Foreign loans may help governments which are struggling to meet basic spending needs for housing, education and health. In addition, foreign companies with a proven track record in the renewable energy sector provide a reassuring presence that may attract even more interest and funding. These foreign companies can provide a “sanity check on whether investments make commercial sense in an emerging sector”, according to Kirsty Hamilton, in a working paper published by Chatham House, a British foreign-policy think tank.

Outside observers are not Desertec’s only critics. Domestic detractors have warned of the potential for foreign partners to unfairly exploit local resources while not providing jobs and cheap energy for locals. They complain of previous experiences with oil and gas exploration companies, which parcelled out large revenues to a political elite and only a few jobs or training for local workers. While Algeria was able to avoid the widespread protests that ousted governments in Tunisia and Egypt, young workers are increasingly frustrated by the lack of employment in the country’s vast energy sector.

Desertec should benefit both sides of the Mediterranean. By helping to diversify and ease Europe’s over-reliance on oil and natural gas from traditional trading partners, the plan predicts saving European energy consumers $40.9 billion annually, according to Desertec documents. Meanwhile, producing countries stand to earn $78 billion a year in export revenue, according to the Desertec Industrial Initiative’s Desert Power 2050 report. So far, Desertec-related projects have sprouted in Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria.

Since 2009, the Moroccan government has committed $9 billion towards a national green energy plan that aims to provide 42% of the country’s energy needs by 2020. Most recently, Saudi Arabia’s International Company for Water and Power (ACWA) signed on to support the first stage of Morocco’s sprawling concentrated solar plant outside the southern town of Ouarzazate, a 160 megawatt (MW) stage of an eventual 500MW facility. Building on a $297m loan from the World Bank in November 2011, the project is part of the country’s broader 2,000MW solar plan and a 6,000MW overall renewable strategy. This initial public-private effort will cost about $500m and includes an agreement with ACWA to handle financing, design, construction and maintenance of the plant. It forms part of Saudi Arabia’s $109 billion solar development plan to ease the local environmental impact of hydrocarbons and increase oil and gas reserves for export.

In neighbouring Tunisia, the TuNur concentrated solar power plant will provide 2,000MW of output for domestic consumption, according to Desertec estimates. Excess energy will be exported to Italy via a 600km high voltage, direct current line.

Late last year, Algeria’s Sonelgaz became the third North African state-owned utility to dedicate some of its future excess renewable energy to European customers. The agreement is a part of Algeria’s plan to produce 22,000MW of solar power by 2030, of which 10,000MW will be sold to Europe.

Despite such interest and fresh funding, achieving Desertec’s goal of creating a green grid that lights up both Mediterranean coasts is many years away. Potential investors are concerned about Desertec’s lengthy schedule and the long wait before they realise a return in revenue. Others are critical of North Africa’s scattered and insufficient energy infrastructure and think such an ambitious project can never overcome these obstacles.

Desertec supporters admit that this planned renewable power grid linking North Africa and Europe is decades away. A 2006 German Aerospace Centre study suggests that Desertec could provide as much as 470,000MW in concentrated solar power capacity in North Africa by 2050. While 38 years is a long time, they reason that these early investments are necessary first steps to a future energy bonanza for the Maghreb and Europe.

Desertec could help unify North Africa economically and politically through joint planning in energy production. Earlier this year, Said Mouline, the director of Morocco’s Agency for the Development of Renewable Energy, told Forbes magazine that the region’s green development represented an opportunity to shift the balance of political and economic influence to the southern Mediterranean.

This is a long way off and requires getting the initial projects up and running. Until the political wind blows steadily, particularly in Egypt and Tunisia, financial investment will not shine on this ambitious North African energy project.