“You must kill the bastards if they threaten you or the community,” said Susan Shabangu to a police forum in 2008 when she was South Africa’s deputy minister of safety and security. “I won’t tolerate any pathetic excuses for you not being able to deal with crime. You have been given guns, now use them. I want no warning shots. You have one shot and it must be a kill shot.” Some blame this statement for the recent police shootings at the Marikana platinum mine on August 16th. Others go further and say the police are incompetent, corrupt and just plain criminals.

South Africa’s Marikana mine massacre, in which police shot dead 34 striking miners and wounded another 78, has taken many sensational turns. First, evidence was unearthed by Greg Marinovich, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist, that only 12 miners were shot in the police fusillade seen on TV and that the other 22 were killed in cold blood when the police allegedly tracked them down and killed them at a separate site, which—according to Mr Marinovich—has since been vandalised.

Then, 270 striking miners were held in police custody (six of them in hospital) and charged initially with the murder of their comrades under a common law rule applied during apartheid and long denounced by the ruling African National Congress (ANC). Julius Malema, the expelled ANC youth leader, was not alone in calling this decision “mad”. As he put it, “even a drunkard could see the police doing the killing on TV”.

Many legal analysts and commentators found this move preposterous and agreed that it was a measure of how desperate the ANC was to avoid having the police —and thus the government—take responsibility for killing the miners. “I can’t believe that (the prosecution service) really believe that any court will ever find the miners guilty…This means they charged the miners with murder knowing full well the charges would never stick, with an entirely different aim,” says legal expert Pierre de Vos.

In a stunning reversal, the acting head of the prosecution service, Nomgcobo Jiba, withdrew the charges in early September. It is difficult to believe that this decision had nothing to do with President Jacob Zuma. Ms Jiba is a close associate of Richard Mdluli, suspended head of police crime intelligence and a strong Zuma supporter, who was facing murder charges until they were withdrawn provisionally. Ms Jiba’s own husband was recently pardoned by Mr Zuma from a three-year jail sentence for theft. Ms Jiba, in other words, is in deep with the Zuma camp and is far too indebted to the president to act independently of him. Consequently, all 270 miners were released between September 3rd and 6th.

These developments follow on the heels of the hardly less sensational fact that no fewer than 194 of the arrested miners are suing the police for torture and attempted murder. The Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID) has verified their complaints. The minister of police, Nathi Mthethwa, has apparently accepted that the police are essentially beyond his control and have been maltreating the arrested. Until their recent release, he had been negotiating to get the arrested men handed over to the prisons department to protect them from vengeful police.

These are only the latest signs that all is far from well with the South African police. In Durban, 30 senior policemen are facing charges of having formed death squads and hiring their services out to criminal gangs, killing at least 28 people in a taxi war. All the leaders of the 30 indicted police are white and the kingpin is a major- general in the police, Johan Booysen.

Meanwhile the Durban metro police have been staging violent demonstrations in central Durban since August, blocking all traffic and searching every motorist, in support of a pay claim. They have even threatened to burn down the city hall. This follows revelations that many senior policemen in the city have become owners of taxi businesses—which they are supposed to be policing.

In Cape Town, the opposition leader and provincial premier, Helen Zille, has set up an official inquiry into the state of policing in the sprawling Khayelitsha informal settlement—Africa’s biggest squatter camp—after a rash of necklacings and other vigilante killings have caused at least 34 deaths, according to newspaper tallies. The minister of police has tried desperately, and in vain, to stop this inquiry, which will inevitably show that a complete failure of policing is at the root of the problem.

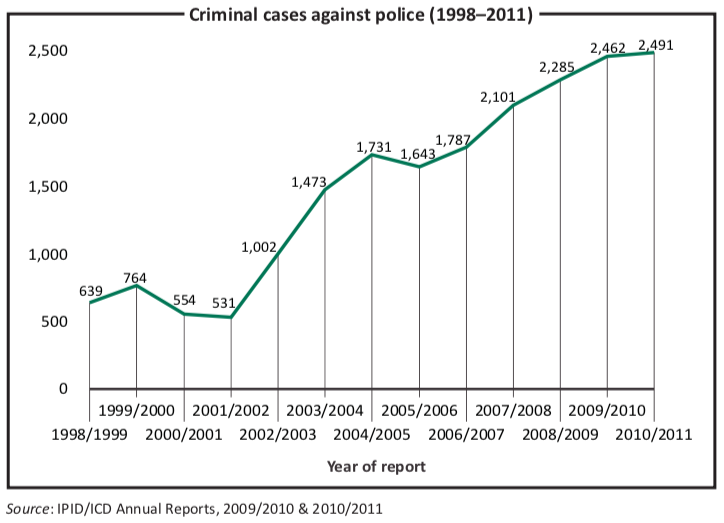

The IPID (formerly known as the Independent Complaints Directorate) records that an astonishing 797 deaths occurred in police custody or as a result of police action from 2010 to 2011. In this same period, 5,869 complaints were received in which policemen were charged with murder, torture, assault or other criminal misconduct. The chair of Parliament’s Committee on Police, Sindi Chikunga, says that complaints of police torture have reached levels “not seen since apartheid”. In its annual report for 2009–10, the IPID

says that complaints against the police increased by 146% in the last 12 years, while the number of cases opened against the police was up by 285% over the same period of time. “I’m afraid of the police,” says newspaper columnist Justice Malala. “Our cops can’t be trusted. Too many of them are linked to too many gangsters and killers.”

For Johan Burger, a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies in Pretoria, the problem began in 1994. “The ANC got rid of almost all the old experienced police,” he says. “The ANC appointed a new leadership essentially on affirmative action lines in which the main criterion was race. They simply weren’t concerned with experience or expertise. Naturally, those people in turn appointed others like themselves and now this sort of mis-appointment has flowed right through the organisation. One result is that there are a number of white, Coloured and Indian police who have never received a promotion ever since 1994 and are bitterly frustrated and cynical. Naturally, discipline just vanishes. We have reached a stage where actually most officers are unsuitable for their jobs. There is also far too much political interference in the police by the ANC. But of course, it is highly politically incorrect to talk about any of this.”

Mr Burger underscores that both the last two national police commissioners have had to quit due to corruption charges and points to the alleged police killing of a protestor, Andries Tatane—seen on prime time TV—in April 2011. Only a few days later Jeanette Odendaal accidentally crashed into a stationary police vehicle outside a Johannesburg police station. A policeman reacted by shooting her dead. On the very same day, April 26, Mr Burger points out, in two separate cases, five policemen were charged with strangling a suspect in custody while another 15 policemen were found to have beaten another suspect to death.

The entire national police should be the subject of a judicial inquiry, Mr Burger says. “The police always try to claim that cases of police misconduct are isolated incidents,” he says. “But it just isn’t so. There is clearly a growing and widespread organisational problem—and ever-growing lawlessness.”

Human rights activist Rhoda Khadalie raises an even more alarming prospect. “We are witnessing a chronic breakdown of authority at all levels,” she

says. “South Africa has become a fragile place. The natives (all of us) are restless. Citizens are easily provoked; protests erupt in a flash; the ANC Youth League is a semblance of the state of the party. Increasing vigilantism and necklacing in the townships; the rape of black lesbians; the murder of foreign nationals; road rage and widespread violence point to a society in deep distress.”

Hermann Giliomee, a distinguished South African historian, concurs. “Remember, this is not supposed to be a nation state. South Africa could easily be six different countries,” he says. “Without strong and clear leadership a process of disaggregation tends to occur. Under [international statesman] Jan Smuts or [Prime Minister Hendrik] Verwoerd there was strong leadership with a clear vision; after that it was just rule by coercion. Now there is no leadership at all and every organisation or smaller unit decides it must just fend for itself and do its own thing. The behaviour of the unions, the police and even the phenomenal rise of the charismatic churches are all signs of this growing lack of social cohesion. The situation is extremely serious.”

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]RW Johnson is based in Cape Town. An emeritus fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford, and a former director of the Helen Suzman Foundation in Johannesburg, he has written ten books, innumerable articles for the Sunday Times (London), the London Review of Books and other publications. He is an expert on French politics and formerly taught at the Sorbonne. He is currently working on a large comparative work on the sociology of political cleavages. [/author_info] [/author]