South Sudan risks economic disaster if it joins the East African Community, but farming could improve the odds and reduce its reliance on oil

by Simon Allison

Regional economic integration is all the rage these days. In development circles, everyone from the African Development Bank to the Mo Ibrahim Foundation praises the benefits of countries working together to remove trade barriers and ease continental cooperation, holding up these alliances as a possible solution to many of Africa’s economic ills.

So when the new nation of South Sudan was born on July 9th 2011, it was only natural for its leaders to look to integrate their stuttering, almost non-existent economy into a regional marketplace. The country’s geographic location in north-east Africa qualifies it for a few different bodies, including the Inter-Governmental Authority for Development (for the Horn of Africa) and the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD), a Muammar Gaddafi-inspired North African bloc.

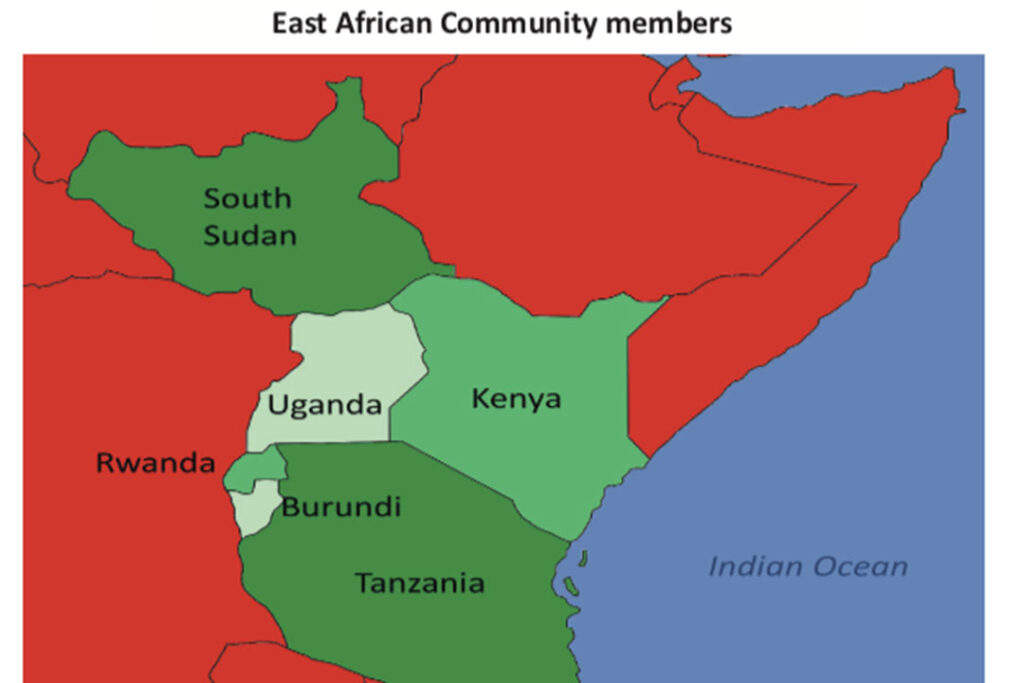

But the obvious choice was the East African Community (EAC), the most progressive of Africa’s regional economic bodies because of its substantive gains in economic integration. Notable achievements include the relaxing of visa restrictions, allowing EAC nationals to work legally in any EAC country, and the gradual removal of border tariffs to allow for the freer movement of goods. It is not yet a completely free common market, but it is closer to this than anywhere else in Africa.

A mere three months after independence, South Sudan applied for EAC membership. This request is still being processed, but it is “a matter of when, not if”, said a senior South Sudanese official involved in the process. The hasty application, however, meant that there was little time for public consultation or a proper assessment of the potentially severe impact of membership. “The proper studies have not been carried out,” said Jeremiah Swaka Moses Wani, undersecretary of the justice ministry.

This sentiment was echoed by Samson Warra, economics lecturer and principal of the University of Juba in the South Sudanese capital. “Citizens were not sensitised to the EAC application. No one knew about it until after the fact,” he told Africa in Fact, criticising the government for operating with a “guerrilla mentality”, which includes unilateral decision-making.

Messrs Wani, Warra and others would have liked a more considered approach because not everyone is completely convinced that joining the EAC will be good for South Sudan. It is Africa’s youngest country and its economy is nascent and unstructured. An influx of cheap goods and services from East Africa, along with a rush of skilled labour, might bring more harm than good.

“Ninety per cent of the economy depends on oil,” explained Mr Warra. “There are no factories, no industries, few businesses. There is nothing to tax.” In 2012 the government took a political decision to stop pumping oil through Sudan’s pipelines, sharply exposing the new nation’s reliance on crude: almost overnight, oil revenue went to zero, forcing the government to suspend major infrastructure projects and withhold paying civil servants for several months.

Although difficult, the decision forced South Sudan to focus on other areas of revenue generation, particularly customs and tax collection. It has also underscored the need for South Sudan to diversify its economy urgently: the oil will run out in the future. (Government officials concede the oil may run out in about 25 years; other experts say it may run out even sooner.)

It is highly unlikely that South Sudan will be able to develop its industry or manufacturing sectors without protection in the form of subsidies or import tariffs. “The concern about South Sudan’s industry and manufacturing sectors is legitimate,” said Abrahim Diing Akoi, planning adviser at the ministry of finance and economic planning. “Our neighbours’ capacity is higher than South Sudan’s. When you have an open-door policy, the people with more capacity will take advantage.”

This is already happening. South Sudan is completely reliant on cheap imports from neighbouring countries as it makes almost nothing of its own, not even basics like soap. Thousands of Ethiopians, Kenyans and Ugandans are flooding Juba. These foreigners are using their better education, access to finance and regional experience to develop small businesses or import products. They are dominating South Sudan’s meagre economic activity.

This has given rise to xenophobic sentiments and violence. In August the Kenyan government grew so concerned about reports of its citizens being killed in South Sudan—nine in the last year alone, according to Richard Onyonka, Kenya’s assistant minister of foreign affairs—that they issued an official protest note to the South Sudanese government. This intolerance is likely only to increase if South Sudan joins the EAC and its neighbours wield their economic clout more strongly. “This will bring bloodshed between South Sudanese and foreigners,” Mr Warra warned.

Charles Anyama, a Kenyan consultant working at the South Sudan Chamber of Commerce, agreed that EAC membership might hurt the economy’s ability to grow but argues that the government has little choice in the matter. No matter what happens, South Sudan cannot compete with its neighbours in terms of industry and manufacturing, he said. “There is no capacity here for that, no skills, and they will take generations to develop.”

It is far better to focus the country’s limited resources on areas where it can develop and have a genuine competitive advantage. This is oil, of course, but also agriculture. Most of South Sudan is part of the Nile River basin. It has vast swathes of fertile, uncultivated land. “The EAC’s common market will help keep South Sudan’s agricultural output competitive, giving it the opportunity to dominate that sector in a way they simply can’t in others,” Mr Anyama said.

This is also the finance ministry’s plan. “Oil is not going to last forever and everyone is aware of that,” Mr Akoi said. To diversify away from oil, the government will focus on infrastructure and agriculture, both of which will benefit from the “international standards and best practices” that must accompany EAC membership. Even better, the EAC will enforce those standards—something South Sudan is not necessarily able to do on its own.

Essentially, by applying for membership of Africa’s most progressive regional body, South Sudan is taking a calculated gamble on agriculture at the expense of any serious local manufacturing or industrial development. The country will continue to import almost everything it consumes, with the exception of food, and is likely to continue to rely on its neighbours to provide a skilled labour force. This is all well and good if the agriculture sector takes off; if it does not, once the oil dries up, South Sudan will have nothing to fall back on.

The question now is whether this gamble will pay off and the country can realise its agricultural potential. Early signs are not promising. Political infighting and a chronic lack of skilled civil servants are hamstringing the government, which struggles to fulfil even the most basic government functions. Thanks to the oil boycott, it is nearly bankrupt. The big test will come when the oil taps are switched back on, giving the government the funds it needs to realise its am- bitions. Ironically, South Sudan’s best chance of diversifying its economy away from oil comes from using its oil revenues effectively by investing in needed infrastructure and skills with an eye towards long-term rewards.