Nigeria: theft of development aid is a subset of broader corruption

by Adeyeye Joseph

When a major foreign funder of one of Nigeria’s biggest public health campaigns threatened to cut vital aid in November 2012, the country’s civil society knew it could be a telling, if not fatal, blow.

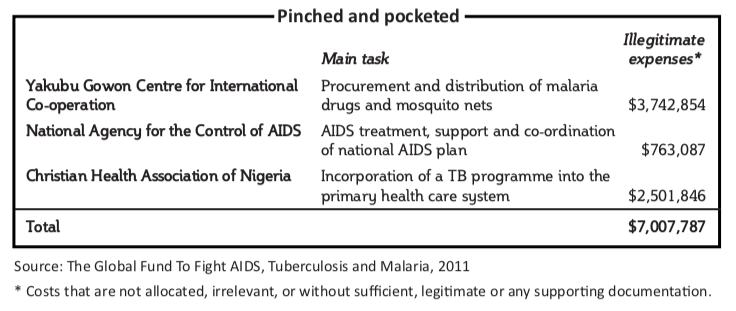

In the preceding six years, the Global Fund to Fight HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria had splashed $474 million on health initiatives throughout Nigeria. But a value-for-grant audit carried out by the fund earlier in 2011 found that three out of its six Nigerian partners had misapplied or misappropriated $7 million in grants. One of the three, the National Agency for the Control of AIDS, is a government body.

Worried that the threat could set Nigeria’s HIV/AIDS campaign back by several years, the attorney general and minister of health quickly formed a task force to investigate the crimes. They vowed to bring its masterminds to justice. But nearly two years later, none of those responsible has been brought to book.

Such failed promises are reflective of Nigeria’s half-hearted approach to fighting corruption, says Joe Okei-Odumakin, one of Nigeria’s civil society leaders. She is not alone. Most Nigerians see the government’s well-publicised anti-corruption campaign as a huge charade.

It is a cynicism that is well grounded. In the past decade, the country’s main anti-graft body, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), has arraigned over 50 senior political figures on corruption charges, including the speaker of parliament, federal ministers, former governors and dozens of legislators.mBut only a few have been convicted. Justice grinds slowly in Nigeria. Some cases are more than 10 years old and are languishing in the courts. Nigeria’s corrupt big men are infamous for side-stepping the country’s inefficient, and sometimes corrupt, judicial system.

Corruption is particularly rife in the oil and gas sector, where a 2012 audit showed that the state oil firm, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation, had failed to remit $4.84 billion in oil proceeds into government coffers.

Theft and misappropriation of development aid are thriving, too. They are a subset of Nigeria’s ubiquitous corruption, Okei-Odumakin says. “The government has not shown interest in prosecuting those who steal aid because of its tolerance for corruption generally. Government officials who steal [from] their country’s budget should not be expected to treat foreign grants or aid differently,” she says.

The theft of grants and aid is also common. “The unfortunate aspect is that some civil society activists are also as corrupt as thieving government officials. We have had cases of non-governmental organisations that were blacklisted by foreign donors because they could not account for funds received,” Okei-Odumakin adds.

Ethiopia is currently the continent’s biggest aid recipient. But Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, with 162 million people, and one of its richest, is also awash in aid dollars. In 2005 Nigeria was second only to Iraq as the world’s biggest recipient of aid and grants, largely because of an $18 billion dollar debt write-off by the Paris Club of creditor nations, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Foreign grant inflows into Nigeria have always been substantial, according to Reuben Alabi, an economist at Ambrose Alli University, Edo State, Nigeria. Though the total value of grants and aid dropped in the oil boom years, it picked up again after the return of democracy in 1999, he adds.

“As a result of the oil boom, Nigeria’s per person income increased sharply, from $250 in 1973 to $1,000 in 1980,” he writes in a paper analysing the impact of foreign aid in Nigeria. This triggered Nigeria’s re-classification as a middle-income country, so official development assistance naturally declined. “The end of the oil boom and the economic crisis of the mid-1980s led to a drastic fall in per capita income; Nigeria was then re-classified as a low-income country in the year 1989.”

Nigeria received $577 million in official development assistance and aid in 2004, $6.4 billion in 2005, and $11.4 billion in 2006, but the amounts fell to $1.9 billion in 2007, $1.3 billion in 2008 and $1.6 billion in 2009 in current US dollars, the latest figures available, according to Alabi.

Corrupt government officials and others steal most of these funds, says Nuhu Ribadu, the former EFCC chairman. “My pet example is the £220 billion [$405 billion] of development assistance that has been stolen from this country since independence to date by past leaders,” he claimed at a 2006 conference in Abuja.

Studies have also shown that foreign aid and grants are often not channelled to critical areas where the majority of Nigerians would benefit. Alabi’s study showed that foreign aid in 2012 was expended mostly on administration, which received 26.9% of total aid. In the same year, 5.4% of aid was allocated to agriculture; 9.4% to energy and mining; 1.9% to industry and trade; and 6.8% to transportation.

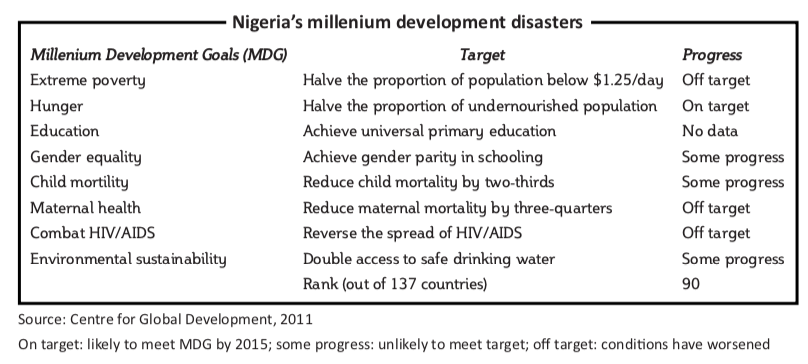

The result is that critical sectors such as education, health and agriculture suffer despite donor agencies pumping millions of dollars into projects in these sectors each year. Not surprisingly, Nigeria’s development indicators have worsened despite four decades of continuous aid. Nearly two-thirds of Nigeria’s people live on less than a dollar a day, according to the country’s National Bureau of Statistics. A third are illiterate and polio, which has been virtually eradicated in nearly all parts of the world, is rebounding in the country’s north.

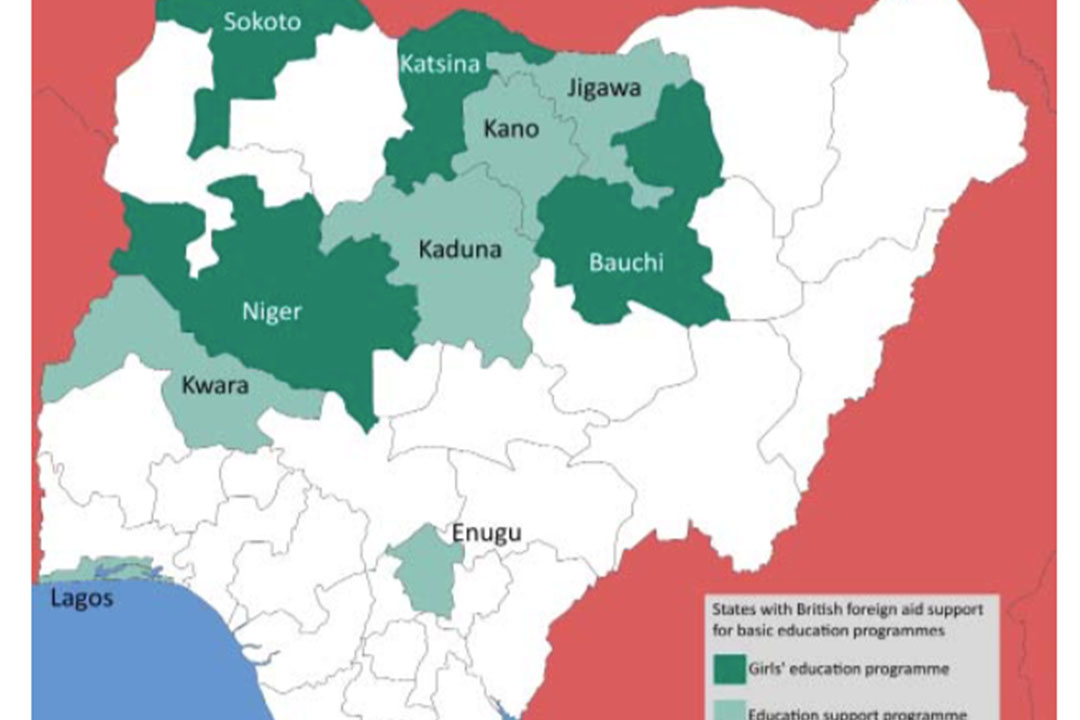

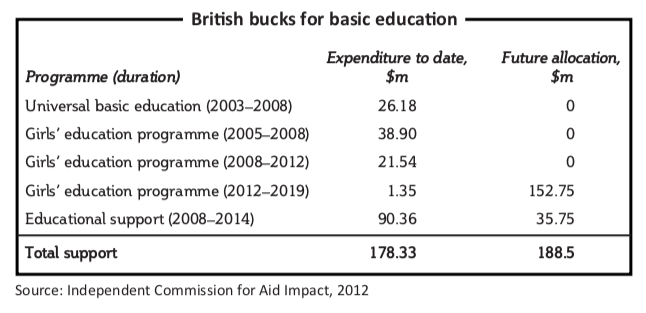

Corruption and the poor prioritisation of aid are mainly responsible for the little impact that donor funds are having on Nigeria’s development. For instance, a recent study by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact, a British watchdog, criticised a six-year primary education programme for its insignificant impact on the community and advised the UK to cancel its funding. An additional £126 million ($188 million) had been budgeted for 2013 to 2019.

“The impact of foreign aid is not felt in Nigeria,” argues Sola Bakare, a lecturer at one of Nigeria’s state universities. “There is a negative relationship between foreign aid and output growth,” he adds.

The way forward is for public and private institutions to block loopholes and ensure that those who steal foreign grants are prosecuted. Transparency is also essential. In 2012, “Nigerian oil exports were worth almost $100 billion, more than total net aid to the whole of sub-Saharan Africa,” said David Cameron, the British prime minister, at the January 2013 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. “Put simply, unleashing the natural resources in these countries dwarfs anything aid can achieve — and transparency is critical to that.”

Debo Adeniran, the chairman of a Nigerian anti-graft group, the Coalition Against Corrupt Leaders, echoes Mr Cameron. “Nigerians should rise to reclaim their country,” he says. “The National Assembly should look beyond cyber crimes or advance fee fraud [called 419 scams after the relevant paragraph in Nigeria’s criminal code] and make legislation that looting [the] public treasury is a crime punishable with severe losses and repercussions on the perpetrators.”

Okei-Odumakin suggests that donors should take a cue from the AIDS Global Fund: conduct more value-for-grant audits and shut the tap when grantees misappropriate funds. “Donors, agencies and countries, should be stricter with those who use funds,” she says. “They should demand accountability and cut off supplies where grant funds cannot be properly accounted [for].”