Kenya’s repetitive school strikes

by Tom Rhodes

Broken government promises and corruption have led to a series of teacher strikes in Kenya. Children are routinely denied an education and are the ultimate victims.

As happens in other East African countries, Kenya’s teachers strike more often than any other civil servants. Since independence in 1963, there have been 12 major teachers’ walkouts, roughly one every four years. In the past four years, teacher strikes have become an annual event.

This year’s strike, which ended July 17th, was one of the longest. The Kenya National Union of Teachers (KNUT) agreed to call off the strike after 24 days of deliberation and political wrangling, capitulating to a similar offer the government made two weeks earlier: a 16.2 billion Kenyan shillings ($184m) deal to improve teachers’ commuter allowances. KNUT, however, had demanded much more: fulfilment of a 1997 government commitment to cover arrears amounting to 47 billion shillings ($540m).

“We are not really very happy,” conceded Wilson Sossion, chairman of KNUT. “We have other components not fulfilled. But the deal improves teachers’ monthly pay and was delivered faster than what was originally offered.”

The KNUT announcement ending the strike came barely an hour after Jacob Kaimenyi, the education secretary, ordered the closure of all public primary schools, fearing the strike would continue another week while administrative staff, among others, continued reporting to work. The education secretary quickly rescinded the order and all Kenyan schools re-opened on July 22nd, spokesman Kennedy Buhere said. Adding to KNUT’s discontent are threats made on July 25th by the government, under the recommendations of the Salary Remuneration Commission, to cut July salaries of teachers who participated in the strike, according to news reports.

Political bickering and union infighting extended this year’s strike, much to the annoyance of Kenyan students and parents. The government accused KNUT of resorting to a strike without exhausting other avenues such as consulting the new remuneration commission, Mr Buhere said.

Meanwhile government ministers appointed to negotiate with KNUT approached the table with rigidity and few skills in arbitration, said journalist Aggrey Mutambo, who followed the negotiations closely. The disputed March 2013 presidential, parliamentary and local elections were a bitter disappointment for the leading opposition party, Coalition for Reform and Democracy (CORD), which encouraged the teachers to continue the strike in a bid to show the weakness and inability of the current government to handle this year’s protests, Mr Mutambo added.

Two competing school unions, KNUT and the Kenya Union of Post Primary Education Teachers (KUPPET), also negotiated with the government separately, further complicating deliberations. KUPPET is a “government union”, designed merely to destabilise KNUT’s efforts, Mr Sossion said disparagingly.

But students were caught in the middle of this strike and their parents had another point of view: “Instead of fighting for teachers they started fighting amongst themselves,” according to Nathan Barasa, chairman of the Kenya National Association of Parents.

Kenyan teachers are tired of poor salaries. “We are the least paid out of all civil servants in Kenya,” teacher Catherine Wanyiri said at a rally in Central Province, Kenya. “All we are asking for are our basic needs.”

While the majority of civil servants are teachers, numbering around 300,000, they are also some of the worst paid, especially in terms of salary increments, said Joseph Karuga, chairman of the Kenya Primary School Heads Association. The government disputes the claim that teachers receive less than their counterparts in the civil service. According to Mr Buhere, the government has harmonised the salaries of teachers with those of other civil servants and, in some respects, pushed salary levels above those of other civil servants. Whatever the case, the average salary of a teacher in Kenya is still low, amounting to 19,000 Kenyan shillings (US$219) a month, according to government statistics.

The ire of Kenyan teachers grew even further after repeated government claims that arrears could not be covered due to increased spending on the expanded federal government required by Kenya’s 2010 constitution. Deputy President William Ruto warned Mr Sossion in their final negotiated agreement that the allowance “cannot be added [to] or reduced…we are operating within a very tight budget”, according to the Daily Nation newspaper.

While Mr Ruto warned KNUT of limited government resources, news reports accused the deputy president of misspending government funds on renovations to his private residence and on hiring a private jet. Newly elected county governors are also implicated in the misuse of the country’s stretched budget. Few county administrations have adhered to the fiscal disciplinary procedures stipulated in the County Government Financial Act and have instead prioritised their own welfare over that of their constituencies. For instance, the budget for Muranga County in central Kenya allocates $7.4m for the construction of a milk processing plant, animal feed factory and fruit processing plant. Yet, the Muranga County assembly has also approved a travel budget of $7.8m for its members.

Teachers have also repeatedly resorted to strikes because the government has repeatedly broken its promises. A 1997 pledge by former President Daniel arap Moi to increase salaries by 150% to 200% over a five-year period never went beyond the first year’s payment. The 1997 offer would have been “fiscally suicidal” for Kenya if it had been implemented, Mr Buhere said.

Mr Moi’s successor, former President Mwai Kibaki, also made pledges offering free primary education without providing sufficient funds to fully implement either promise. But government offers of free primary and secondary education (for 2003 and 2007, respectively) significantly increased enrolment rates, while funds for increased teacher hires did not materialise. Kenya’s primary school population jumped from 5.9m in 2002 to 7.6m in 2005, according to UN figures.

Parents have ended up picking up the costs of school fees and other levies since the annual government subsidy is insufficient, providing only 10,165 Kenyan shillings ($117) per secondary student and 1,020 shillings ($12) per primary one, said Mr Barasa, head of the parents’ association. “If the government offers free education then it has to be free, not some middle ground.”

Meagre funding for Mr Kibaki’s free education initiative is partly due to massive graft within the education ministry. As finance minister under Mr Kibaki’s government, Uhuru Kenyatta (now Kenya’s president) presented the results of an internal investigation in June 2011 that found 4.2 billion Kenyan shillings ($46m) had gone missing from the ministry, according to news reports. Both the United Kingdom and the United States have pulled their donor support for the free education initiative because of this corruption.

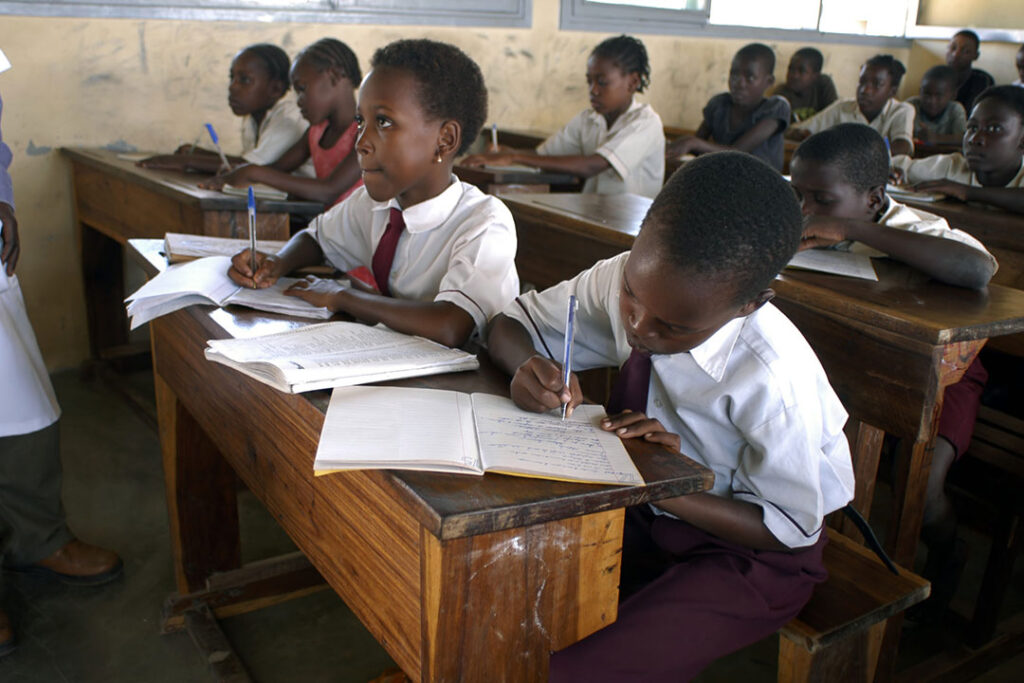

While teachers battle the government, pupils suffer. “I am not happy because I am not in class; it is in school that I meet with friends,” said primary school pupil Stephen Oluock, 11, sitting idly in his home in the Mathare slum, one of the more dangerous residential areas in the capital, Nairobi.

Students lost four weeks of class time due to the strikes. They also forfeited two weeks during the election period last March when schools were used as polling stations. In all, students lost 108 lessons, crucial studying time for the upcoming national exams.

On July 23rd the government agreed to extend the second and third terms to help students catch up on lost lessons, Mr Kaimenyi announced.

The routine teacher strikes, rooted in poor government policy, have contributed to generally deteriorating education standards, including a 40% dropout rate in schools, Mr Barasa said. Limited textbooks and widening teacher-to-student ratios have also contributed to the declining standards. There are now on average 80 students per teacher as opposed to 45 students per teacher in 2005, Mr Barasa said.

High marks in the national exams are crucial for placements in Kenya’s top-ranking secondary schools. As the October to November national exam period approaches, poor students are inadequately equipped and this contributes to the widening gap between rich and poor. “If we continue in this vein we are going to see elite students taking the lion’s share of top public secondary school placements,” Mr Barasa said. Often emanating from expensive private primary schools, where teachers never strike, students from rich families perform better in the national exams and readily obtain placements in Kenya’s highly-competitive top secondary schools.

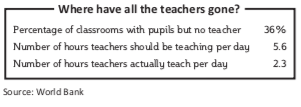

Uncommitted, underpaid and sometimes moonlighting teachers, especially those from poor rural areas, are also to blame for the deteriorating education standards. According to a World Bank survey of service delivery indicators for Kenya, children in public primary schools are taught for fewer than three hours per day as opposed to the official five hours and 40 minutes. This is often due to the absence of teachers who supplement their income with extra work outside the classroom.

“I remember in March our headmaster would hardly make an appearance,” Mr Mutambo said. “He had a tractor so he would spend his days leasing it during ploughing season instead of [performing] his school duties.”

Accustomed to long, almost annual teacher strikes and routine teacher absences from class, many poor Kenyan students are induced to take matters into their own hands. Peering into the classroom of the Hope Compassion Centre Primary School in Mathare, two very young girls are at the blackboard. Pupils Esther Adongo and Evelyne Gatwiri instruct fellow students in Kiswahili and maths in a classroom without a teacher. When Esther is asked why she is teaching her peers, she answers with a shrug. “This student teaching is normal here,” she said. “Sometimes our teachers are absent for long durations.”