Senegal’s Quranic students beg to learn

The government struggles to balance Muslim values with protecting children

“Sarakh, sarakh,” demands a barefoot child wearing a dirty, torn Pokémon t-shirt and oversized cargo pants held up with a scrap of rope. He holds out his hand to passersby on a busy street in Senegal’s capital city, Dakar. “Sarakh, sarakh,” he repeats. “Charity, please give me charity,” he is saying in the Wolof language. A man drops a coin into the tomato sauce can that hangs around the boy’s neck. The boy glances down, and then moves towards a taxi that has just pulled over to the curb. “Sarakh, sarakh,” he says, reaching his hand into the open window. “Sarakh, sarakh.”

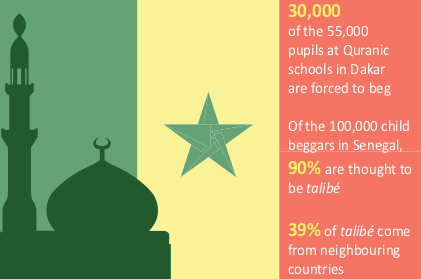

This is not a unique sight in Senegal. Each day, tens of thousands of young boys take to the streets of the French-speaking west African nation to beg for money and food. Known as the “talibé” (the Arabic word for “learner”), most of these boys are students at so-called Quranic schools, where “teachers” force the boys to bring back a set amount of “alms” each day. If the boys do not meet their daily quota, they risk beatings and sometimes torture.

“The rights of these kids are being violated,” said Niokhobaye Diouf, the director of Senegal’s ministry of women, family, children and vulnerable groups. “These children are being exploited in the name of the Quran and it is insulting. It is a violation of human rights.”

The talibé often live in cramped, squalid quarters and suffer from extreme physical abuse, according to Human Rights Watch (HRW), an international pressure group. The boys, some as young as four or five years old, spend upwards of six hours outside each day, under the hot sun, darting across busy roads and weaving through traffic in hopes of finding a generous stranger. A 2010 HRW report found that the average talibé in Dakar must collect between 300 CFA (Communauté financière africaine) francs and 1,000 CFA francs (US$0.60-$2.00) in spare change each day, in addition to two kilograms of rice and 20 sugar cubes. They must bring everything they earn back to their teachers and religious guides, known as “marabouts”.

“If they fail to bring back the set amount, the boys are often beaten [by the marabout],” said Matt Wells, a west Africa researcher for HRW and author of HRW’s 2010 and 2014 reports on the Senegalese talibé. Others are tied up, chained to furniture or beaten with canes and electric cables. “We’ve documented cases that reach the level of torture in terms of the severity of the beatings. Sometimes young boys are forced into stress positions for a long period of time as punishment.”

International and local human rights groups say that while Senegal has many “good” Quranic schools, hundreds of others are abusing and exploiting their students. Of Dakar’s estimated 54,837 Quranic students, more than 30,000 have practised begging as part of their schooling, according to a survey earlier this year by the justice ministry’s anti-trafficking unit.

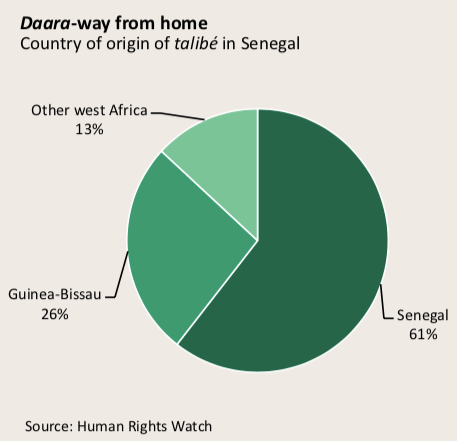

Families send their boys to receive a “proper” Islamic education at Quranic schools, known as “daaras”, under the care of a marabout. About 40% of the talibécome from neighbouring countries, such as Guinea-Bissau, according to the HRW report. Marabouts recruit young boys from rural villages to daarasin bigger cities. Once the boys arrive, they often have no contact with their parents. Very few learn the Quran, and even fewer learn basic reading and writing skills, according to HRW. Some avoid the abuse and run away to live on the streets.

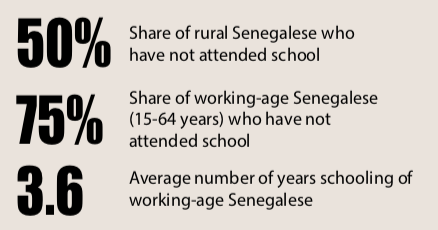

For years the Senegalese government has tried to end this practice of forced child begging and to improve the regulation of Quranic schools. “Senegal has long had strong laws and policies on the books to protect children from exploitation, but the government has consistently failed to enforce them in relation to wide-spread forced child begging,” Mr Wells said. “The result is thousands of boys whose only education is in how to survive on the streets, while those to whom they were entrusted make often lucrative profits from their labour.”

Despite a 2005 law that criminalises profiting from forced begging and child trafficking, activists say the talibé problem is worse than ever. “The children who beg on the street are becoming more and more numerous,” said Guirane Diene, the director of a local non-profit organisation that helps Senegal’s youth. “I just can’t understand why the state doesn’t do more.”

Senegal’s government has repeatedly vowed to fix the problem, particularly in the aftermath of a deadly fire in March 2013 that broke out at a daara in Dakar’s Médina neighbourhood. A marabout had locked up about 40 boys inside the school. Most escaped, but eight died.

Following local outrage, authorities vowed to start enforcing the 2005 law. The government authorised a national child protection strategy in December 2013. It created an action plan to end child begging by 2015.

But as of March 2014, despite clear evidence of ongoing widespread abuse and exploitation, HRW found that the government had shut down only one Quranic school for safety reasons and had prosecuted only one case of forced begging.

In addition, for the past year lawmakers have been drafting a new legal frame- work. This proposed law would require: marabouts to be certified, specific daaracurriculums, inspection committees to ensure theboys are not abused or neglected as well as health and safety standards. Under the draft legislation, authorities have the power to shut down any religious schools that do not comply.

Current laws prescribe schooling standards only for secular schools and do not apply to daaras. The constitution says religious institutions and communities have the right to regulate and manage their affairs independent of the state.

The draft law, which the National Assembly was expected to debate in April, has since been delayed without explanation, possibly to avoid stirring religious controversy before local elections scheduled for late June, after this magazine went to print. Once tabled, most expect the law to pass. Its enforcement, however, is less certain.

Authorities blame their poor progress in ending the exploitation and abuse of the talibé on the strong opposition they encounter in applying such laws. Senegal’s population of 13.6m is 96% Muslim, according to the US-based Pew Research Center. As a result, the country’s spiritual leaders wield much influence and insist that begging is an essential part of learning humility.

“Teaching the Quran is legal, so the government cannot be allowed to regulate Quranic teaching,” said 47-year-old Alya Simé, a Quranic teacher in Dakar. “Religion and state are two separate things. The government can’t police the maraboutsbecause they [the government] are not in charge of religion in this country.”

Mr Simé claims that he has never forced any of his students to beg on the streets, but admits that he knows many marabouts who do. The money the talibé collect is often the only source of income for the marabout, who is not paid by the state for his teaching services, he explained.

“I see those boys out on the street, and it pains me,” Mr Simé said. “But what can I do? They are not my students. My students come to me each day for lessons. They learn the Quran, they do their studies. That is all.”

Awa Ndour, with the justice ministry’s anti-trafficking unit, said the proposed law is not about controlling religion. “There are some people that think that the regulation of daaras is just to fight against Islam. But it’s not that,” she said. “It’s about combatting the trafficking of children and ending the exploitation of the talibé.”

Child rights advocates say that while passing the proposed law would be an important step forward on paper, harsher penalties must be imposed on those who break the law. More importantly, authorities need to have the courage to stand up to the religious community and follow through on their commitment to help the talibé.

“The authorities must finally show the determination to end this exploitation,” HRW’s Mr Wells said.

This includes getting police to report and investigate cases of children found begging on the streets, as well as giving the courts the ability to prosecute cases without fear of consequences. Confronting a marabout can cost votes, hinder or end a career or lead to social exclusion. A high-level government official received death threats in 2005 after trying to prosecute an abusive marabout, according to the 2010 HRW report. An entire village shunned a father who tried to prosecute a religious teacher who beat his son. Often spiritual leaders will come together and rally behind a marabout or protest any prosecution or legislation.

HRW say that in addition to closing down daaras that are violating the boys’ rights, the government should support Senegal’s numerous “exemplary” daaras, ones with qualified marabouts, that provide superior education, a clean, safe place to live and learn, and do not force the boys to beg.

However, more must be done to change people’s attitudes about alms and begging. Most Senegalese report giving money, food or both to the talibé at least once a day. Despite their concerns about the boys on the street, many believe helping the less fortunate is part of their duty as good Muslims.

“I think, first and foremost, that the state is responsible for the welfare of children in our country, as well as for their right to a proper education,” said Mamadou Wane, the coordinator for the Dakar-based Platform for the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights, a coalition of some 50 organisations that work to end forced child begging. “But society is also responsible. If people stopped giving to children in the street, there wouldn’t be begging.”

The justice ministry’s anti-trafficking unit says it is currently working on a media campaign to educate people about the dangers and abuse the talibé face. While a possibility exists that this may make people feel even sorrier for the boys, the operation aims to make people realise that giving alms encourages maraboutsto exploit the boys. The hope is that people will be outraged enough to rally for the boys’ welfare and pressure the authorities to regulate the daaras.

But many residents say they are not optimistic forced begging will stop any time soon. “Is this problem ever going to end?” asked Amadou Koita, a 30-year-old construction worker in Dakar. “I hope so, for the sake of the boys on the street. But unfortunately, I don’t think so. It is too ingrained in our society.”