It took the International Criminal Court (ICC) ten years to convict and sentence its first offender. As it enters its second decade, is it an impartial court or are some governments manipulating the ICC to investigate cases against rival opposition groups?

In the ten years since the ICC first came to life, the tribunal—meant to serve as a criminal court for the world—has served exclusively as a criminal court for Africa. All seven of its investigations—Côte d’Ivoire, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Kenya, Libya, Sudan and Uganda—have been on the African continent.

In March the court convicted its first suspect, an African. It found former Congolese militia leader Thomas Lubanga guilty of war crimes for conscripting and enlisting children in the DRC. He was sentenced to 14 years’ imprisonment in July.

Completing the African theme pervading the ICC’s first ten years, it is perhaps fitting that the court now heads into the future with an African at its helm. In June this year, Fatou Bensouda, a much-respected former attorney-general of her native Gambia, succeeded the deeply unpopular Luis Moreno-Ocampo as chief prosecutor.

The Rome Statute that founded the ICC entered into force on July 1st 2002 after ratification by 60 countries, all in Africa, Europe and Latin America. Some criticise the court for being too focused on Africa. Unlike the other two continents, Africa has many long-standing conflicts. This has created opportunities for the court to investigate and prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity on the continent. But states can also refer cases to the ICC, and many African states have done so.

A number of African leaders, however, have used this self-referral mechanism to politicise the court by asking the ICC to investigate their rivals, even when they themselves are implicated in allegations of gross human rights violations during conflicts and civil wars.

Côte d’Ivoire provides a recent example. Widespread killings and other atrocities were alleged on both sides of the fighting between 2010 and 2011. An ICC investigation began after then-chief prosecutor Mr Moreno-Ocampo acted proprio motu (on his own initiative).

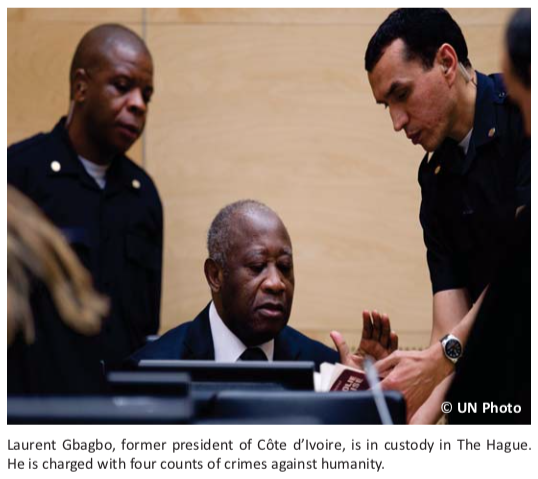

In reality, however, President Alassane Ouattara wrote to Mr Moreno-Ocampo inviting him to exercise this power against his rival, former president Laurent Gbagbo. In exchange, critics allege that Mr Ouattara hoped for a light touch in the investigation into crimes committed by his own forces.

Mr Gbagbo is now in custody in The Hague, the first head of state and so far the most high-profile suspect to be taken to the ICC. Investigations against Mr Ouattara have not been forthcoming.

“The situation in Côte d’Ivoire has fuelled the perception that the ICC is highly politicised,” said a senior legal source close to the court, who did not want to be named.

“It was Gbagbo who accepted the jurisdiction of the court in 2003 allowing preliminary examinations, and so much progress was made. Then when Gbagbo lost favour with the West and Ouattara came to power, the ICC moved in and arrested him right away. Everyone knows that the chief prosecutor was playing to the West,” the source said.

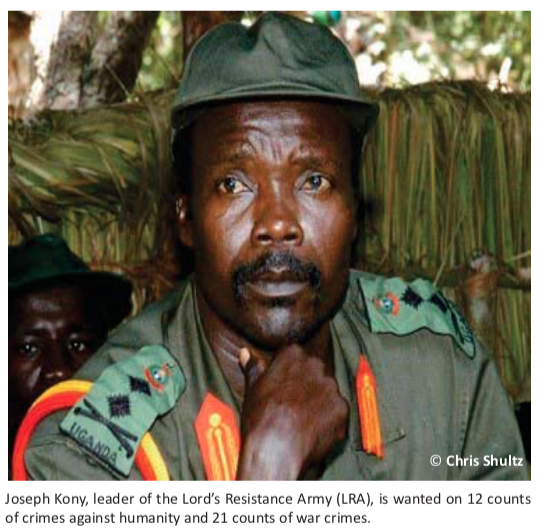

The tendency of the court to strike deals with regimes whose own records are highly questionable has also prompted strong criticism in the DRC and Uganda, where the arrest warrant for Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) leader Joseph Kony—made notorious this year through the viral film “Kony 2012”— sidesteps the role of Ugandan government forces, also accused of gross human rights violations.

“Various African governments have assisted the ICC in exchange, seemingly for exemption of their own political officials,” said Ms Keri Leicher of Consultancy Africa Intelligence, a South African- based research firm. “In the cases of the DRC and Uganda, over a year of negotiations between prosecutors and local officials took place before these states agreed to any referrals. Many critics therefore claim that deals were struck and promises made to convince these respective governments to cooperate, and that the ICC has to date avoided pursuing criminal cases involving Congolese or Ugandan officials despite the various atrocities committed by these forces against their own people.”

The ICC has a much older heritage than its recent 10th birthday would suggest. Inspired by the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials after the Second World War, and the temporary tribunals of the last two decades, the ICC has advanced the growing reality of international criminal justice.

The international criminal tribunals for Rwanda (ICTR) and the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), created by the United Nations (UN), paved the way for the ICC. They set a precedent for modern courts to try those deemed most responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Not just the institutions, but crucially the jurisprudence of these courts has formed part of the corpus of international criminal law applied by the ICC’s judges.

But the ICC stands apart from its predecessor tribunals, and subsequent UN- created courts such as the Sierra Leone Special Court, which sentenced Charles Taylor to 50 years on May 30th 2012 and the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (better known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunals). Unlike these ad hoc tribunals, with a mandate limited in time and scope, the ICC is the first permanent institution to enforce international criminal justice.

It also differs from the UN’s principal judicial organ, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), in that the ICC prosecutes individuals, whereas the ICJ does not. The ICJ’s role is to decide, in accordance with international law, any legal disputes submitted by UN member states and to give advice on legal issues to

UN bodies and agencies. The ICC, in turn, is an independent organisation not part of the UN system, although the Security Council can refer cases to the court.

Where ad hoc tribunals mainly investigate post-conflict situations, the ICC deals with ongoing situations. It often launches investigations during the early stages of an unfolding conflict, such as its recent efforts to conduct preliminary investigations during the Islamist occupation of northern Mali.

In addition to the potential for politicisation, these features propel the ICC into frequent controversies. Libya and the ICC, for example, issued separate warrants for the arrest of deposed dictator Colonel Gaddafi’s son Saif al-Islam and former spy chief Abdullah al-Senussi. This brought the ICC into sharp conflict with Libyan authorities. Libya refuses to hand over Mr Saif al-Islam to The Hague and Mr al-Senussi was recently extradited from Mauritania to Libya. Libya demonstrated its frustration earlier this year by detaining four ICC employees, and will conduct the prosecutions in its national courts.

The UN Security Council referred Libya’s cases to the ICC, the only way a state that does not accept the court’s jurisdiction can be brought before the court. Yet two of its five permanent members—the United States (US) and China—have not ratified the Rome Statute and do not accept the ICC’s jurisdiction on their territory. The result is that the US and China can use their position to refer situations to the court, but never be prosecuted themselves.

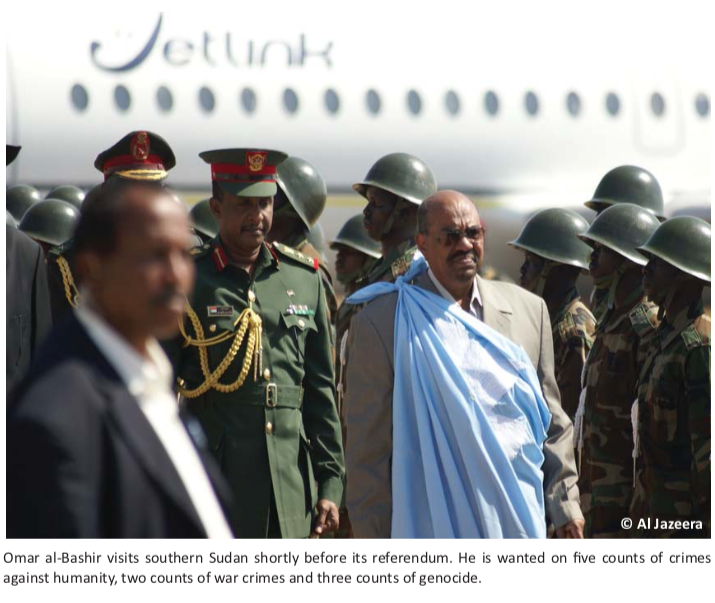

Perhaps the most serious structural problem facing the court is its inability to enforce its rulings. This is best exemplified by events in Sudan, where a highly publicised arrest warrant issued for President Omar al-Bashir in March 2009 continues to be defied brazenly not only by the Sudanese government but by most members of the African Union.

The ICC faces many challenges going into its second decade. The Arab Spring and the ongoing atrocities in Syria have heightened the importance of obtaining the participation of Arab nations—all currently non-signatories, except for Tunisia.

The perception of unfair targeting of African states is set to continue unless abuses on other continents begin receiving more attention. So far, opportunities to investigate crimes in Afghanistan, Colombia, Georgia, and by the British in Iraq, have been largely missed, fuelling the view that the court is an imperialist instrument of Western governments.

Yet many close to the court feel the positive force of a new dawn. In August, the trial chamber that convicted Mr Lubanga reached a landmark decision on reparations for victims. This opened a whole new area of jurisprudence for the court and could go some way to answering claims that victims have not been at the forefront of its work. In 2010 the crime of aggression was added to the Rome Statute, despite the fierce opposition of the US as bystander. So far only Liechtenstein has ratified the new offence.

With a conviction finally under its belt, a new chief prosecutor, a former head of state in custody and a celebrity status that other courts can only dream of, there is no doubt that the ICC—flawed as it may be—is determined to make its mark on the world’s emerging legal order.