Angola’s murky oil deals

The rebuilding of an Angolan railway reveals a confluence of hidden interests

On the border between Angola’s eastern Moxico province and the southern Katanga region of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a Chinese-made iron drag- on—the Benguela railway—is poised to cross the Kasai River and so re-establish Angola’s rail links with the rest of Africa for the first time since 1975.

The rebuilding of the bridge will restore the 85-year railway link between the deep-water port of Lobito on Angola’s Atlantic Ocean coast, 34km north of Benguela, and the mineral wealth of Katanga province. Katanga has 40% of the world’s copper reserves and accounts for half of global cobalt supplies, according to the US Geological Survey. The original rail bridge was dynamited in 1978 on the orders of Mobuto Sese Seko, the late despot of Zaire, as the DRC was then known.

Once one of the world’s most profitable and strategic railway lines, the Benguela line ceased to operate across the Kasai during Angola’s 1975-2002 civil war. While the line on the Congolese side of the river remains mostly operational, if run down, the Angolan section was destroyed as the cold war played itself out via local proxy forces.

The restoration of this rail route is a key component of the Southern African Development Community’s Transport Master Plan, launched in 2011, which aims to revive the Lobito Corridor and the land- locked economies of the DRC’s mineral-rich Katanga province and Zambia’s copper belt.

But a closer examination of the project reveals a re- markable confluence of hidden interests that may have hugely benefited a small handful of players, including leading figures of the Angolan political elite and the world’s third-largest private oil and metals trader, Trafigura, based in Switzerland. This partnership has quietly gained control of Angola’s railway infrastructure, fuel distribution network and iron-ore deposits through a global network of off-shore companies registered in various tax havens. It provides some in- sights into the battle unfolding in the new scramble for Africa’s mineral riches.

In 2005 the China Railway Engineering Corporation began rebuilding Angola’s three existing railway lines from scratch, at an estimated cost of $3.5 billion. The Hong Kong-registered China International Fund (CIF) raised the funds, according to AidData.org, a research group which tracks development financing. CIF has close and shadowy ties with Angola’s state-oil firm, Sonangol, and is also known as China Sonangol.

All three Angolan rail links are now fully restored: a 907km link from the south- ern Namibe port to Menongue, close to the former Cassinga iron mine; a 538km line between Luanda and Malange’s diamond mining area; and the 1,336km Benguela track linking Lobito on the coast to the Katanga border.

With Lobito and its 200,000 barrel per day refinery under construction only about 2,000km away, the Benguela line holds a massive strategic advantage over any other supply routes via Tanzania or South Africa. Currently all minerals from Katanga are exported via Richard’s Bay in South Africa, about 8,000km away by train or truck.

Angola’s transport ministry said last year that the Benguela line was expected to carry 20m tonnes of goods by 2015. Since hardly any Angolan industrial activity takes place along this stretch, it is clear that the agenda is to capture most of the Katanga mining business. With fuel and transport making up about 50% of a mine’s operational cost, whoever can supply petroleum and logistics has significant price-making power over the southern DRC’s mineral riches.

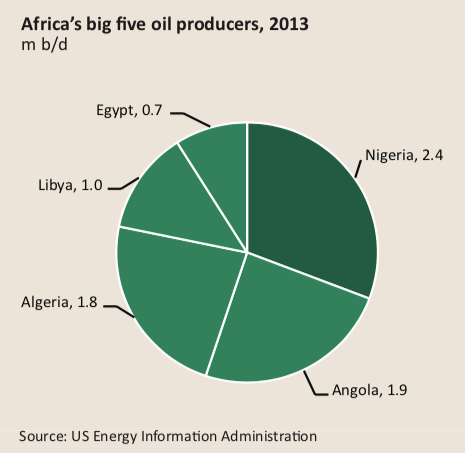

Angola is Africa’s second largest oil producer after Nigeria. Although it pumps about 1.9m barrels of crude daily (b/d), its re- finery in Luanda is run down and can meet only local demand for lubri- cants. As a result, Angola is a net fuel importer.

Starting in late 2008, Trafigura stepped in to help manage Angola’s petroleum imports. With operations spanning 56 countries, it provided the Angolans with a sophisticated international logistics chain and the discretion of its off-shore-based trading havens in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) and Singapore, as documented in a 2013 report by the Berne Declaration, a Swiss NGO that monitors corporate transparency.

In 2010 Trafigura bought out BP’s sub-Saharan distribution network (excluding South Africa), which stretches from Walvis Bay on Namibia’s Atlantic coast to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania on the Indian Ocean. This system covers all of Zambia and includes a massive new fuel depot in Kolwezi, the centre of Katanga’s mining industry.

With this purchase, the Trafigura-Sonangol relationship developed into a much more ambitious union to become the dominant fuel distributor in Angola and southern Africa.

In 2010 a company called Cochan, solely-owned by General Leopoldino do Nascimento, Angolan President Eduardo dos Santos’s chief of communications, bought a $213m stake in Puma Energy International (PEI), a Trafigura subsidiary. PEI deals primarily in petroleum products. According to the prospectus published in February on the Luxembourg Stock Exchange’s site, Cochan owned 18.75% of PEI’s shares. Mr do Nascimento’s share was later reduced to 15% and is now worth $750m, at what many call a hefty profit for “General Dino”, as he is commonly known in Angola.

While Mr do Nascimento retired from his government post in November 2013, he is currently one of the directors of the DT Group, the logistics, fuel distribution, property and mining conglomerate that manages Trafigura’s investments in Angola.

In September 2011 Trafigura sold a 20% stake in PEI to Sonangol, “creating further links between the Angolan beneficiaries and the Swiss company”, according to the Berne Declaration report. Sonangol bought a further 10% stake later on at a cost of $500m. “That means that…45% of a $5 billion multinational is owned either by the dos Santos regime or General Dino,” wrote Michael Weiss in an article in Foreign Policy magazine in February 2013.

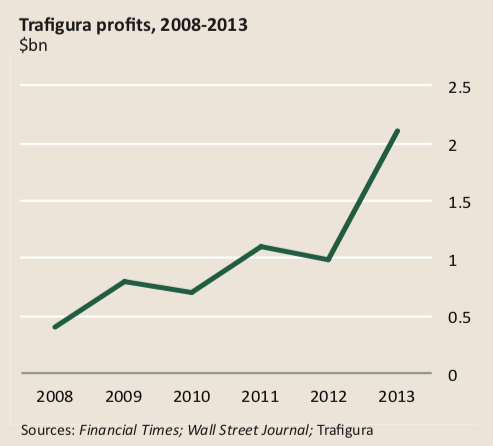

By 2012, PEI was a $20 billion per annum business, according to the Berne Declaration. Trafigura’s declared profits leapt from around $440m in 2008, according to Reuters, to just under $2.2 billion in 2013, according to Trafigura.

A little digging reveals the link to the Benguela railway line. The DT Group’s website notes that Vecturis, a Belgian-based railway specialist, manages Ango- la’s rail logistics. The state gazette shows that Vecturis (Angola) is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the DT Group, with 1% of its shares allocated to the Escom Group, the commercial trading arm of Banco Espirito Santo (BES), a Portuguese private bank and long-time dos Santos sup- porter. Vecturis in Brussels failed to respond to phone calls or e-mails enquiring about its relationship with the Angolan company of the same name.

Isabel dos Santos, the president’s daughter, owns an 18.75% shareholding in BES, part of her sprawling $4 billion empire, Portuguese banking records show. BES’s Escom also holds logistics, mining and fuel distribution interests in the DRC, according to their public records.

Across the Kasai, the DRC’s national railway company, the Société Chemin du Fer du Congo, has sub-contracted the reconstruction of the Katangan railway system to Vecturis (DRC), funded by a $375m World Bank soft loan. It was not possible to access Vecturis DRC company records, but there may be a large degree of overlap between the three Vecturis entities.

The Benguela line, while ostensibly a national asset, has private objectives, ac- cording to Angolan investigative journalist Rafael Marques. It follows a persistent pat- tern of corruption among the Angolan elite, he said. As part of its grand plans for Katanga, the Angolan government is currently building a new international airport at Luau, the town on the Kasai through which the Benguela line runs. It is also building a new massive container depot and warehouses in this town of only about 12,000 people, according to a local official.

“All that operation in Luau is tied to [Angolan] military ambitions for the control of Congolese resources for the profit of the Angolan ruling elite, and their foreign business associates,” Mr Marques charged.

Considering that Angola does not have a single mine within 600km of Luau, there seems to be good reason to believe him. It appears that the treasures of several African countries are controlled by an opaque and unaccountable business collective. The fight for this fortune, it seems, is getting murkier.