Uganda’s crippled opposition

The ruling NRM, fused with the state, keeps a firm grip on power while opposition parties suffer internal organisational failure

In its early years after independence, military regimes and single-party dictatorships ruled most African countries and competitive elections were rare.

From the early 1960s to the end of the 70s, only about 55 elections were held on the continent, averaging three per year, wrote American political scientistsDaniel Posner and Daniel Young in 2007 in the Journal of Democracy. Most of these were not competitive, multi-party polls; they were merely referenda to endorse autocratic rule.

Incumbent parties and their leaders won all these elections with the exception of Somalia’s first president, Aden Abdullah Osman, who lost to Abdirashid Ali Shermarke in 1967. (Mr Osman set the record as the first African president to step down peacefully after serving two terms.)

A slight improvement took place in the 1980s, with about 36 African elections, or 3.6 per year. Again, not a single incumbent party lost, in Mauritius, in 1982.

In the next decade, a wave of democratisation in Eastern Europe set in motion a renewed push for competitive party politics in Africa. From 1990 through to 2005, Africa held more than 100 elections, averaging at least seven elections each year.

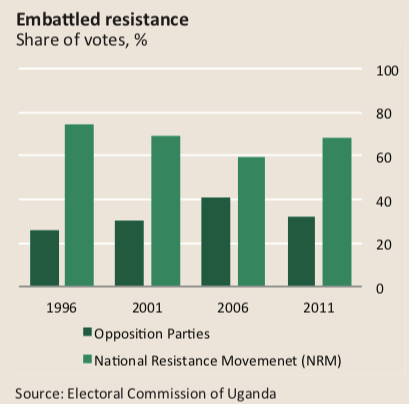

Currently, at least ten general elections are held in Africa every year. Yet one constant remains: a weak opposition and dominant ruling parties. The latter still win 80% of all elections held.

Opposition parties’ victories in national elections have been few and scattered—in Benin and Zambia in 1991, Ghana in 2000 and 2008, Kenya in 2002, Côte d’Ivoire in 2010, Senegal in 2012, Zambia again in 2012, Malawi in May 2014.

Uganda is an unambiguous example of a single-party system and a weak and fragmented opposition. The country’s experience with multi-party politics is tenuous. From independence in 1962 to the capture of power by Yoweri Museveni’s guerrilla rebels in 1986, only one multi-party election was held: in 1980 when Milton Obote’s Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) defeated the Democratic Party (DP) and the Uganda Patriotic Movement (UPM) in a highly disputed election.

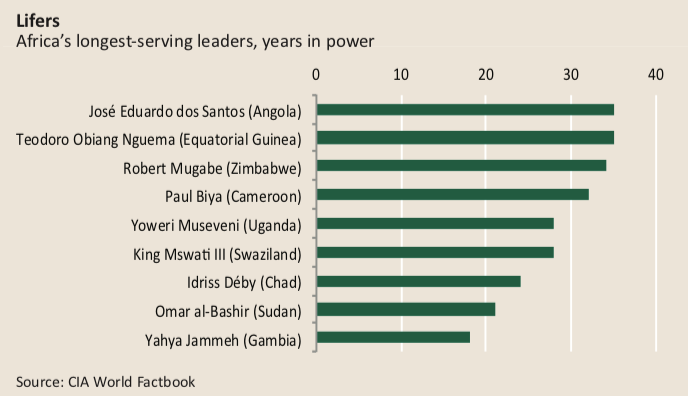

Since 1986, the NRM has maintained a firm grip on power. Its chairman, Mr Museveni, now 70, will be running for a record fifth five-year term in 2016. Having ruled unelected up to 1996, Mr Museveni’s combined stay in power by 2016 will total 30 years, making him one of Africa’s longest-ruling authoritarian leaders.

In a rather bloated national legislature of 385 seats, including unelected members of cabinet, the ruling party holds an absolute majority of 295 backed by a few dozen independents. The combined opposition has only 60 members of Parliament (MPs). This dominance is duplicated at the local, district and sub-county levels.

Mr Museveni has exploited legal and extra-legal manoeuvres to cripple opposition to his increasingly authoritarian rule. Shortly after assuming the presidency, Mr Museveni banned political parties for 19 years until a 2005 referendum restored multi-party politics.

He is quick to chide his opponents: “There is no genuine opposition in Uganda,” but rather “political careerists and purveyors of falsehoods”, he told a victory party in the capital Kampala after the March 2011 elections.

The structure of Uganda’s national politics, the historical interplay between society and state and the internal weakness in political parties have crippled the country’s opposition. Three factors explain why.

First, much like other African countries with little experience in liberal principles, the ruling NRM continues to promulgate an environment that is hostile to multi-party politics. From Mr Obote’s single-party system of the 1960s and Idi Amin’s dictatorship in the 70s to Mr Museveni’s no-party politics in the 80s and 90s, the military has played a preponderant role and displaced competitive elections.

“In those countries where the military has been a key political player—in Angola, Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan, Rwanda, Sudan, Uganda, etc.—state resources are deployed to ensure retention of power by the ruling party,” said Augustine Ruzindana, deputy secretary-general of the main opposition party, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC). Thus, “mobilisation, membership recruitment, and fundraising are made impossible or difficult for opposition parties,” Mr Ruzindana added.

In Uganda, the state is synonymous with the ruling NRM. The state’s coercive machinery is directed at defeating the opposition as witnessed during the 2011 walk-to-work protests against high food and fuel prices.

The NRM and Mr Museveni equate opposition with subversion of the state, making Uganda’s political structure fundamentally unprogressive. While in developed democracies official opposition is a government-in-waiting, “in Africa, opposition parties are seen as detractors and enemies of the ruling parties or even the nation,” noted Asnake Kefale, a politics professor at Addis Ababa University, in an e-mail correspondence.

Second, Africa’s limited experience with open and competitive politics means there are no long-standing political constituencies aligned to clear ideological persuasions, according to Richard Joseph, a political science professor at Northwestern University in the US.

Instead, parties are founded on religious affiliations, regional and ethnic blocs, as was the case with Uganda’s independence parties UPC, which is mainly Anglican and based in the east and north; and the DP, largely Catholic and rooted in central Uganda.

Today religion and ethnicity play a less prominent role. But the main opposition party, FDC, nevertheless lacks a clear-cut political constituency. It is neither a party for workers (a very small fraction of the population) nor the middle class (equally very small) nor the peasant masses (who are the majority).

Without a political base, the FDC cannot raise funding from party members. “Most people will find it easier to contribute [to] weddings and burials the year round than contribute on a sustained basis to political party activities,” said Mugisha Muntu, a retired army general and now FDC president.

Third, and arguably most important: the state controls material resources in a country where the ruling party is firmly entrenched. Uganda is one of Africa’s most privatised and liberalised economies. But the state remains a big business player and indirectly wields a financial whip.

“There is a desk in the Internal Security Organisation that monitors all business activities remotely associated with the opposition,” three-time losing presidential candidate, Kizza Besigye, said over lunch in Kampala in July. Such businesses are denied government tenders, targeted by the tax agency and subjected to other crippling government constraints, he said.

For Frederick Golooba-Mutebi, columnist for the East African newspaper, a vital problem for opposition parties is that “they have no money”. Unable to raise funds, Uganda’s opposition parties cannot recruit and retain quality leadership and a credible following. “They have limited reach: no party structures, hardly any regular contact with their supposed supporters and members, and total absence of activities geared at recruiting new members,” Mr Golooba-Mutebi added.

Critics and opposition leaders accuse the NRM of gross incumbency abuse. Incumbency, however, can backfire when confronted with a well-organised opposition, for at least two reasons.

First, precisely because of perceived and actual incumbency advantages, ruling parties suffer succession struggles as members jostle for positions when a long-reigning ruler finally bows out. This happened in Ghana in 2000 (with Jerry Rawlings) and Kenya in 2002 (with Daniel Arap Moi). It could have transpired in Uganda in 2006 had Mr Museveni not bribed MPs to remove term limits, as reported in local and international media and alleged by some MPs.

Second, the electorate can be rallied to vote out the incumbent party for its poor performance. Organisational failures within the FDC and other opposition parties, however, have prevented holding the NRM to account in Uganda.

To have a fighting chance, Uganda’s opposition parties need to organise and mobilise robustly to overcome constraining political and economic obstacles. They need to broaden their base by leaving their headquarters in Kampala and campaigning in the countryside. Instead of relying on external donors, the opposition need to tap into local funding sources such as the small middle-class and business community. To beat the state’s coercive machinery, the opposition should craft an appealing message and an alternative national vision.