Capital-intensive agriculture in Africa may boost food supply but could also cultivate hunger

by William G. Moseley

Corporate interests have hijacked African food and agricultural policy. They are behind a new green revolution for the continent that is pushing a capital-intensive approach with farms, supply chains and expanding international markets. This approach is a step backward to concepts of food security prevalent in the 1960s and 1970s. As a result, Africans will remain hungry.

Up until the early 1980s, international experts had laboured under the misperception that sufficient food supply—a function of homegrown production and net imports—was equivalent to food security. As such, it was argued, the best way to fight hunger was to boost agricultural production, as exemplified by the green revolution. United Nations experts monitored food supply in relation to the caloric needs of a country—known as the food balance-sheet approach—and then assumed that all was well if the two sides were at least equal.

Amartya Sen’s 1981 publication, “Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation”, blew apart this food security idea. Mr Sen, winner of the 1998 Nobel prize in economics, argued that hunger was much more about inadequate financial and physical access to food than the market availability of sufficient quantities of food.

History is riddled with examples of the poor dying of hunger when food was plentiful. Classic amongst these is the famine which wracked the West African Sahel during the early 1970s. While people were dying of hunger in Senegal, Mali and Niger, peanuts—a key sauce ingredient and source of protein across the region—were being exported to Europe.

Mr Sen’s definition of food security, with its attention to access, dominated international food policy circles for about 15 years, from the late 1980s through the early 2000s. Then, after a 20-year hiatus, the global community’s attention shifted back to agriculture. The international consensus on “food security as access” shifted to a technocratic focus on food production as the best way to solve global, and especially African food insecurity.

Beginning in the mid-2000s, momentum started to build amongst donors, foundations and corporate allies for a new green revolution in Africa as the best way to address food insecurity. Building on the belief that the first green revolution (an international effort to bring hybrid seeds, fertilisers and pesticides to the South) had largely bypassed Africa, the idea was to launch a similar effort tailored to African crops and conditions. Gone was the emphasis on “access” to food.

The problem is that combatting household food insecurity involves more than just increasing food production. A food security approach that is sensitive to issues of access targets the poorest of the poor who are habitually the most food insecure. Helping poor households in rural Africa feed themselves in an affordable manner means introducing low-cost, sustainable enhancements to farming. These improvements include intercropping or the mixing of more than one crop in a field, agro-forestry, the blending of trees and crops, composting, and soil conservation measures. These reforms are critical because they enhance soil fertility and control pests without cash outlays for expensive chemicals and fertilisers.

Sadly, advocates of the new green revolution for Africa are not pushing these types of interventions. Rather, they envision a more capital-intensive approach to agriculture involving supply chains, increasingly large producers, agro-processors, expanding international markets, and farming with intensive, and often expensive, inorganic fertilisers, pesticides and seeds. This view sometimes legitimises long-term land leases by foreign entities, so-called land grabs, which are seen as a showcase for new production strategies. While this approach will likely improve agricultural production in sub-Saharan Africa, it will do little to improve household food security for the poorest.

How is it that the donor community shifted, in a few short years, from an access-based approach to food security towards one that emphasises food production above all else? Blame a narrow production focus and international corporate interests. The Group of 8 (G8), the world’s richest democracies plus Russia, launched the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition (NAFSN) last May. This $3 billion commitment by the G8 plus 21 African and 27 multinational companies aims to lift 50m people in Africa out of poverty by 2022.

The programme’s level of collaboration and coordination with international agri-business is unprecedented. “The private sector can increase food availability by not only increasing investment in production but also by linking smallholder farmers to broader markets and creating incentives for innovation that improve productivity,” according to a United States Aid for International Development (USAID) fact sheet on the initiative.

While ostensibly a G8 initiative, the NAFSN is primarily a US-led programme. Given the close links between this initiative and the business community, one could argue that those in American aid circles have learned from China, where development assistance has very tight links to Chinese business interests. The more likely explanation, however, is the rise of philanthrocapitalism in the US, where former and current business leaders, through the strength of their foundations, have increasingly come to influence the shape and direction of US international development programmes. Central to the philanthrocapitalist world view is a belief that private enterprise is the fundamental agent of progressive change and that business acumen trumps other forms of expertise.

It is also very convenient when a company’s profit motive lines up nicely with an initiative promoting the end of African hunger. This is, perhaps, an updated take on the old assertion that “What is good for General Motors is good for America” (albeit in the context of a globalised economy this time around).

While nearly 30 companies are involved with the NAFSN initiative (from Syngenta to Monsanto), let us look at the efforts of Cargill, a US-based large agricultural, financial and industrial corporation. It is a telling example of how companies frame issues of global food and hunger. Greg Page, Cargill’s chairman and chief executive, has been particularly active on the talk circuit and in the op-ed pages of American newspapers, articulating his support for NAFSN and similar initiatives. Cargill is a massive company, with revenues of $133.9 billion in 2012, which would rank No. 8 on the Fortune 500 list if it were publicly traded. It operates in 66 countries with some 133,000 employees. Mr Page has described Cargill’s business as “the commercialisation of photosynthesis”. In voicing his support for the NAFSN approach, Mr Page outlines the need for free trade, growing crops where there is a comparative advantage to do so, property rights reform, and access to fertiliser, quality seed and mechanised equipment.

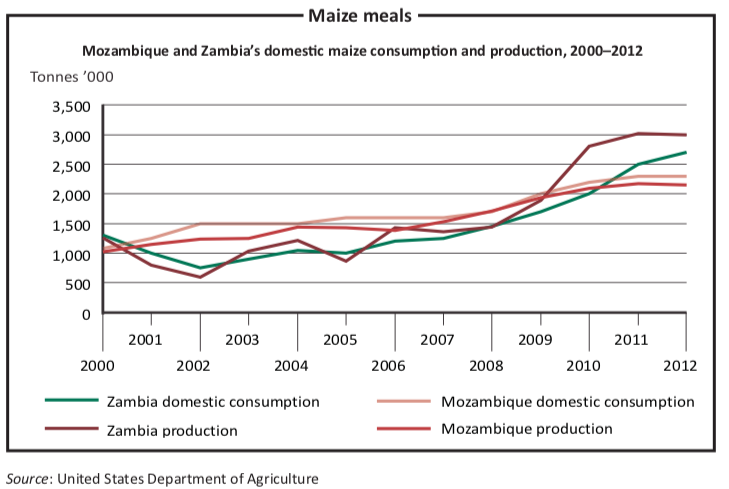

In a July 2012 speech in Minneapolis, US, Mr Page compared Zambia and Mozambique. Cargill does a considerable amount of business in Zambia, which allows 99-year land-use permits that can be transferred between buyers and sellers, or transferred from one generation of farmers to the next, Mr Page said. This type of policy encourages agricultural investment, spurring food production in the country, he argued. Last year Zambia produced a million more tonnes of maize than the country could eat— and Zambia is now a “net exporter in a continent of food shortage,” he added.

In Mozambique, however, land-use rights are conferred for half the length of time and permits are non-transferable between parties, Mr Page said. “If you look at the soil types, the rainfall patterns and everything else, there is no demonstrable reason that Mozambique should not produce more food than Zambia, and yet in the absence of the right legal frameworks, they’ve not been able to do that.”

What Mr Page fails to understand is that producing more food in the aggregate is not synonymous with improving household food security. While Zambia may now be a food exporter, this does not necessarily mean that Zambia’s historically food insecure groups are better off. Instead, food insecurity remains a major issue for certain segments of the population, including child-headed households and those taking care of orphans (largely due to HIV/AIDS), the unemployed in urban areas, and smallhold farmers in the drought-prone, southern and western parts of the country (where an overreliance on drought-vulnerable maize has made the situation even worse). Furthermore, the Zambian government, because of its market-oriented land tenure legislation, has leased 8.8% of its agricultural land to foreign entities, according to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation.

These companies and foreign governments are primarily interested in producing food for export. Their interventions have done little to improve household food security amongst poor Zambians.

It is time we realised that, amid all the fanfare for a new green revolution in Africa, and the upsurge in donor and corporate interest in African agricultural production, the best way to address food insecurity for the poor—emphasising access and not production—has regressed. Why? The big money, for input providers, agro-processors and traders, is in building more capital-intensive and market-integrated African farming systems. There is little to no profit to be made from eradicating hunger.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]William G. Moseley is the chair of geography at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA. His research interests include tropical agriculture, food security, land reform, and environment and development policy. He is the author of over 60 peer- reviewed articles, as well as several books, including most recently, “Taking Sides: Clashing Views on African Issues”. [/author_info] [/author]