South African small grocery businesses need to learn lessons, and so do legislators

Informal retailing offood and drink accounts for some 54% of all township micro-enterprises and is a critical business activity for economically marginalised South Africans.

Most significantly, spaza shops represent the dominant grocery trading business in the townships. There are over 140,000 of these micro-enterprises nationally, collectively trading over R42 billion worth of goods a year, according to 2016 figures from Neilson.

Nevertheless, not much data is available on the economic impact and scale of such informal businesses, particularly with regards to the scope and scale of self-employment in contexts such as township settlements. Moreover, South Africa’s efforts to engage or support such enterprises through appropriate and effective policy efforts have been minimal, despite their important role in food security and local employment.

Following extensive anecdotal reports of increasing foreign national ownership of township spaza businesses, researchers from the Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation (SLF) revisited a township in Delft, near Cape Town, where they had carried out research in 2010/2011 as part of a study of micro-enterprises around the country.

Their aim was to examine the nature of change in the local grocery economy, given that a shopping mall was being built near the suburb (Delft South) where they had previously carried out research.

Using a “small-area census approach”, we aimed to identify and log the GPS co-ordinates of all existing micro-enterprises (including grocery retailers) within the suburb, a 2,93km2 area of 11,000 households that is home to 43,185 people. We also conducted interviews with spaza business owners, using a semi-structured questionnaire to establish product pricing, enterprise operations and business challenges. The research was undertaken over a three-month period from June to August 2015.

During our earlier research, we identified some 879 micro-enterprise activities, including 177 spaza shops. The underlying residential environment and Interestingly, the spaza sector was one of only two business categories that declined in number in Delft South, with some 32 categories considered.

All the other categories experienced considerable growth between 2011 and 2015. While some activity in certain business categories might have gone undetected in the initial survey, the growth in enterprise types other than spaza shops was startling.

In takeaways (364%), tailoring services (355%), street trade (776%) and in the sale of meat, poultry and fish (391%), for example, the data revealed an astounding growth of activities. Also noteworthy was the growth in liquor retail – predominantly, the very small micro-enterprise variety – which increased by 32%. This was remarkable, given the risks of illegal liquor trading. Such micro-enterprise growth places the decline in spaza shop numbers in a startling context. There had been an enormous expansion of informal business activities in that time.

The size of Delft South’s local population had changed little since 2010/2011, but in 2015 we found that the number of spaza micro-enterprises in the neighbourhood had decreased, with some 152 outlets now operating, representing a decline in outlets by 14%. The growth of street trade and informal businesses has meant a decline in spaza shop numbers.

In 2010/2011, spaza shops and smaller “house shops” accounted for one third of identified micro-enterprises, whereas in 2015 these forms of grocery retail outlets represented only about 15% of these businesses. Nonetheless, food, drink and groceries still dominated, in numerical terms, the range of micro-enterprise activities within the Delft informal economy.

Furthermore, within the spaza sector, of the 177 shops originally identified, some 126 (70%) had ceased trading by 2015. Only 53 shops had continued to operate from the same premises, though in many cases the ownership had changed. A mere 12 shopkeepers recalled participating in the 2011 survey. Local residents reported that spaza shops were frequently bought and sold, even changing hands between entrepreneurs of different nationalities. It was clear there was considerable fluidity in the sector.

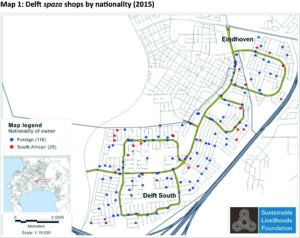

Immigrant businesses have found a role in Delft by responding to market opportunities through providing more competitive services and by introducing innovation. In 2010, ownership of spaza outlets on the site was evenly split between South Africans and foreign migrants. At that time, they were Somali and Bangladeshi nationals. In 2015, however, some 82% of the 157 spaza shops remaining in the district were owned by immigrant entrepreneurs, predominately Somalis, Ethiopians and Bangladeshis. Most of these outlets were operated by employees of the owners, who were rarely seen in Delft.

Through extensive interviews with local shopkeepers, the researchers learned that the dominance of foreign shopkeepers in Delft South was due to their ability to leverage competitive advantage through a range of business models and strategies.

These varied from shop to shop and nationality to nationality, but commonly included supply chain wholesale linkages, integrated distribution networks, price discounting, retailing of contraband cigarettes, labour practices based on kinship, and maintaining multiple retail outlets under centralised ownership.

It was apparent that immigrant traders and South Africans in the sector had sought to gain competitive advantage through aspects and combinations of the above practices, but the evidence indicated that entrepreneurs who embraced informal processes had generally been more successful.

Informal economic survivalists, especially South Africans who exclusively operated single operator and micro-business models, were vulnerable to business failure. The township grocery market had become an increasingly contested business space.

The ability of supermarket chains and their holding companies to influence municipal regulation and land-use zoning is a major inequity compared to the limited power and political influence of township micro-enterprises. The business and policy environment greatly favours the rise of formal businesses over the emergence of a new class of township entrepreneur.

It emerged, for instance, that the City of Cape Town had sold off a 9.7ha site adjacent to Delft to Shoprite Checkers, a South African supermarket chain. In 2016 it was announced that a shopping mall would be built on the site. Supermarkets and shopping malls often include high-street liquor and takeaway businesses. These business-outlet types alone would directly compete with over half the nearby township economy.

By actively facilitating shopping-mall development near the township, yet making no allowance for informal business, local government and big business form a highly effective partnership to out-compete and dominate the township retail grocery sector. The new mall will form a localised monopoly of formal retail businesses – against which no township grocery retailer can hope to prosper or grow beyond its current informal status.

Overall, the second round of research in Delft South revealed a story of demographic and competitive change within the township informal retail grocery sector (much of it replicated across South African townships). While this change has in many cases led to reduced prices for township grocery consumers, it has come at considerable cost to South African-owned micro-enterprises.

Foreign entrepreneurs have increasingly embraced their informal status and capitalised on weak governance, and they openly oversee trade in products such as contraband cigarettes while using non-normative employment models.

Furthermore, supermarkets and malls, due to their size and scale, have the power to procure land, change land-use zoning, and leverage their businesses in ways far beyond South African independent spaza owners.

As such, many South Africans have ended up sandwiched between these two extremes: on the one hand, they are too survivalist in orientation to embrace informality, but on the other they are too small to command influence from the state. Both of these factors squeeze survivalist business opportunities out of the township economy.

Combined with the unfortunate reality of recurrent xenophobic violence and social and economic upheaval, this means that the informal sector in South Africa is nationally significant – and it needs appropriate policy intervention. Policies that help to ease the legal and technical processes for formalising informal businesses are urgently needed. Town-planning laws need to incorporate the residential reality of township informal grocery retailing. A national system that brings spaza businesses of a minimum size into the regulatory framework, where their activities can be better overseen, is also needed.

As the Delft South research shows, future shopping mall developments must be required to satisfy social and economic impact assessments for their impact on local micro-enterprises. At least 25%, or indeed more, of their retail space should incorporate local township businesses, and supermarkets should be required to carry a proportion of stock produced by smallholders.