Mozambique: the comeback

A long-time opposition party comes out of the bush and returns to the political stage

A poster affixed to the crumbling exterior of Renamo’s campaign office in Maputo, Mozambique’s capital, shows Afonso Dhlakama as a much younger man. The photograph of the opposition leader—thick, 1980s- style coiffure and large, rimless spectacles—is a throwback to the cold war era.

This image, used in every presidential contest for the past 20 years, created an even more striking juxtaposition during the 2014 race. Mr Dhlakama, now in his mid-sixties, with snow-peppered hair, campaigned in front of giant billboards plastered with this picture of his younger self. It was Mr Dhlakama’s fifth unsuccessful bid for the presidency since agreeing to end a long civil war in 1992 and transform his rebel movement into an opposition party. Renamo is the Portuguese acronym for the Mozambican National Resistance.

Early results of the October 15th presidential and legislative polls had Mr Dhlakama losing out to Filipe Nyusi of the ruling Mozambique Liberation Front, known by its Portuguese acronym: Frelimo. The incumbent president, Armando Guebuza, was constitutionally prevented from seeking a third term.

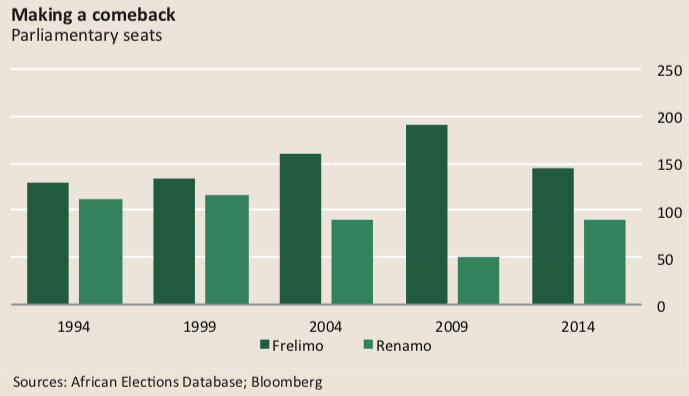

Despite Mr Dhlakama’s disappointed response—he has called the elections a “masquerade”—the results suggest that he and his party succeeded in winning back a large chunk of the electorate lost over the past decade. Mr Dhlakama looked set to garner at least 36% of the vote, coming a respectable second to Mr Nyusi with about 58%. Renamo was expected to up its parliamentary seats substantially from 51 to close to 90 against against Frelimo’s 140 seats in the 250-member Parliament.

In the late 1990s Renamo had more than 2m voters. Ten years later its support had slumped to under 700,000. After narrowly losing to Frelimo’s Joaquim Chissano in 1999, Mr Dhlakama garnered just 16% against Mr Guebuza in 2009. Shortly after this dismal showing, Mr Dhlakama moved from Maputo to the northern city of Nampula and was rarely seen in public.

It helped that in 2014 his main opponent was Mr Nyusi, a former defence minister, but a virtual political unknown. Still this does little to explain the remarkable comeback of this opposition figure many had already relegated to the scrapheap of history.

The “Dhlakama effect”, as it was widely called during the run-up to the polls, was the campaign’s big surprise. People crammed onto rooftops to hear him speak and streamed onto landing strips to greet his plane.

Curiosity was part of it. In October 2012 Mr Dhlakama relocated to a remote civil-war era camp in the foothills of the Gorongosa mountains, in Mozambique’s central region. The move was timed to coincide with the 20th anniversary of the end of the civil war between the then Marxist Frelimo and his forces—aided by apartheid South Africa and the white-minority regime in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. Many of those who came to see him wanted to see for themselves whether rumours that he had been assassinated in the bush were really false.

I first met Mr Dhlakama in late 2012 at his camp in Satunjira, where I interviewed him for the French news agency, Agence France Presse. Living in a mud and grass hut, he was a lonely but determined figure. He believed Frelimo would send assassins for him and surrounded himself with soldiers.

It was easy then, to dismiss him as a hangover from the cold war as he reminisced about South Africa’s former president, P.W. Botha and Jonas Savimbi, the Angolan rebel leader. Yet Mr Dhlakama had made some shrewd calculations about the “interests” he was likely to disrupt by his move to the bush.

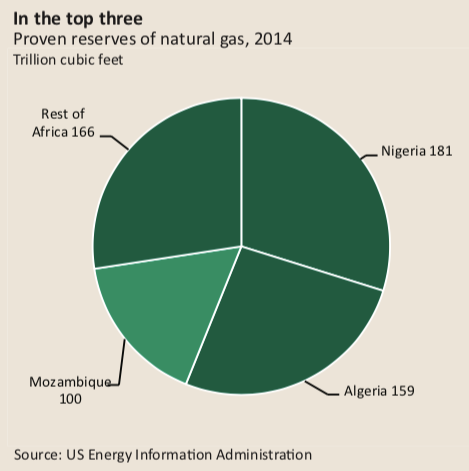

Foreign coal companies depend on a rail-link running through central Mozambique, where he and his followers had holed up, and big oil companies were closely monitoring the country’s stability ahead of an expected natural gas boom in the north.

Mozambique’s proven natural gas reserves (in the far northern Rovuma basin) jumped from 4.5 trillion cubic feet to 100 trillion cubic feet in 2014, placing it third in Africa behind Nigeria and Algeria, according to the US Energy Information Administration. The country is also starting to exploit one of the world’s largest coalfields in the north-western region.

Mr Dhlakama threatened to disrupt the export routes if his demands were not met. These demands included greater representation on electoral organs and the reintegration of Renamo fighters into Mozambique’s armed forces. He accused the Frelimo government of government of breaking the 1992 peace agreement by denying public service jobs to opposition members and purging the armed forces of Renamo men. The peace agreement had stipulated a 50-50 split.

“There will be confrontation,” Mr Dhlakama warned. This was necessary “for us to have finances”, he said. Mozambique’s natural resources had altered the political game, he explained. Renamo argues that the Frelimo ruling elite has kept the economic opportunities resulting from the resource windfall to itself. “This is not the Renamo of yesterday,” he said. “This country is ours.”

While the return to full-scale civil war that many feared did not materialise, there were casualties on both sides in April and October 2013. The Frelimo government of Armando Guebuza was heavily criticised for its failure to find a negotiated way out of the impasse.

Official silence surrounds the true cost of the fighting. No official figures were ever confirmed but local media suggested that government forces had suffered high fatalities in fighting near Dhlakama’s Satunjira camp. Suspected Renamo militants killed scores of civilians.

“There are a lot of doubts about what happened in Satunjira, people are very sceptical,” said Elizabete Azevedo-Harman, a research fellow with the London-based Chatham House, a London think-tank. “So they start…[saying), “Is Renamo right? Were they really trying to kill [Mr Dhlakama] or not?’” she added.

After months of negotiation, Renamo and the Frelimo government signed a peace pact on September 6th at the presidential palace in Maputo. The lavish ceremony was reminiscent of the signing of the 1992 peace accord. Many of the same players were present. As in 1992, Italian diplomats and Catholic clergy played a key role in bringing Mr Dhlakama in from the cold, travelling into the bush to fetch him. Former President Joaquim Chissano—who signed the 1992 accord—looked on as Mr Dhlakama did the honours again, this time with Mr Guebuza his signing partner.

The negotiation had borne fruit. In April 2014 the Frelimo-dominated parliament approved changes to the existing election laws, allowing opposition parties greater representation on electoral organs. Renamo won extra seats on the National Electoral Commission and opposition party members were appointed at every level of the secretariat that is charged with running the polls. All participating parties were allowed to nominate staff to man polling stations.

On the eve of elections, the government gave in to another of Mr Dhlakama’s demands, agreeing to integrate Renamo fighters into the army and police and also to give financial aid to veterans too old for service. While not all items on Mr Dhlakama’s original list of grievances had been ticked off, it was enough for the opposition leader to sign the peace accord paving the way for his return.

In the vacuum left when Renamo boycotted the 2013 local elections, a rival opposition party, the Mozambique Democratic Movement (MDM), mopped up support in some of Renamo’s former strongholds like Zambezia and Nampula provinces. Many predicted the MDM, under Renamo-breakaway Daviz Simango, would supplant Renamo as the official opposition in 2014. That was not to be: Mr Dhlakama’s return to the mainstream political fray was dramatic and decisive.

Capacity crowds greeted him in traditional Renamo strongholds like western Tete and central Beira, hailing him as a “saviour” and a “survivor”. Even in Maputo, a traditional Frelimo fiefdom in the south, thousands of supporters banged drums and danced around his car.

“He is a good person. He fought for us,” said 20-year-old Nelson (who declined to give a last name), one of many young people who came out to see Mr Dhlakama in Maputo, frantically snapping pictures on his mobile phone.

Like Nelson, many of those drawn to Mr Dhlakama’s campaign were too young to remember the 1962-1992 civil war, in which an estimated 1m people died. Yet they remember Renamo’s recent skirmishes with government forces in central Mozambique.

“For a lot of the youth he represents…anti-Frelimo spirit,” said Chatham House’s Ms Azevedo-Harman. “For the new supporters it is about the last two years.” Mr Dhlakama, she says, embodies “someone who forced Frelimo to give up something, someone who stopped Frelimo.”

The MDM’s Mr Simango was the real loser in the 2014 polls. Early estimates say he garnered less than 8% percent of the presidential vote. The MDM looked set to increase its parliamentary presence from eight to just under 20 seats. The party tried, unsuccessfully, to leverage its image as a “civilian” alternative to the two “armed” Frelimo and Renamo parties. [to be updated]

Instead, Renamo’s ability to strong-arm political concessions from the ruling elite “confirmed people’s intuition that only through strategic demoralisation of Frelimo it is possible to achieve meaningful change”, said Victor Igreja, a Mozambican anthropologist. Where that leaves the democratic process in Mozambique remains to be seen.

As for Renamo’s long-term political survival, much will depend on whether it can overcome its long-standing weaknesses, in particular its top-down, military-type leadership structure, which has seen other strong figures pushed out over the past few years.

In returning to the bush and reviving a cold-war conflict, Mr Dhlakama may have played his trump card. It will not be easy for him to resort to military tactics any time soon and still save face. Even though he condemned the 2014 polls as having been a “masquerade”, he promised the international community he would not resort to violence.

Mr Dhlakama hinted that he would push for some form of “negotiated solution” with Frelimo. Negotiations of this kind, however, have never been Dhlakama’s strongest suit. “He is always good at running campaigns,” Ms Azevedo-Harman said. “He is charismatic and easy with people…but he is terrible post elections.” Ms Azevedo-Harman pointed to Mr Dhlakama’s inability to negotiate with Frelimo successfully following previous polls.

In the meantime, rank-and-file opposition members hope to see their ageing leader prove his relevance in a new era. With the recent natural resource discoveries, this period holds great promise for Mozambique, but perhaps even greater risks: the spectre of regional conflict. The gas-rich far north is separated by thousands of kilometres from the capital, Maputo, the seat of economic and political power, which is also resource-poor. Renamo’s stronghold, the central region, is strategically located in between.