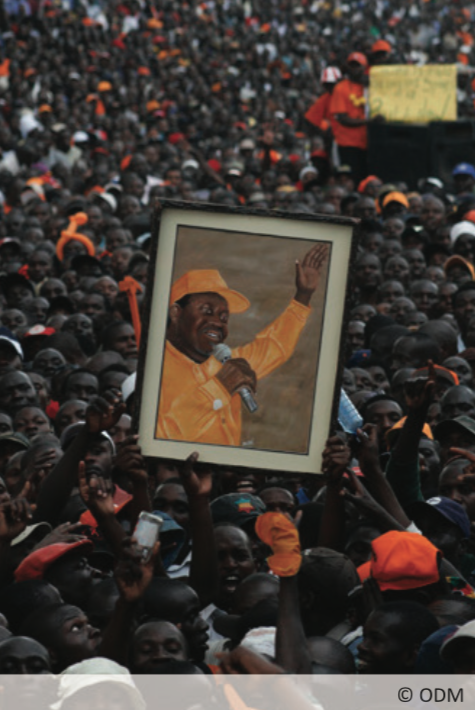

Kenya: has Raila Odinga lost his taste for battle?

The faded promise of Raila Odinga’s opposition coalition is part of a disheartening pattern in Kenyan politics

Raila Odinga cut his political teeth as a dogged opposition fighter in the 1990s. He was imprisoned three times for anti-government activity under former president Daniel arap Moi. His campaign to unseat Mr Moi’s successor, Mwai Kibaki, led to the violent 2007-2008 impasse and his appointment as prime minister in a unity government. But since his defeat to Uhuru Kenyatta in the March 2013 elections, Mr Odinga has gone uncharacteristically quiet.

In 2013 Mr Odinga’s party, the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), joined the Wiper Party and the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy-Kenya to form the Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (CORD). Mr Odinga ran for president on the CORD ticket with Wiper’s leader, Mr Kalonzo Musyoka, as his running mate. CORD lost to Mr Kenyatta’s Jubilee coalition in a close-fought and contested election.

“CORD appears to have lost direction,” said Jason Ondabu, a political analyst. “It is thriving more on public rallies than on holding Jubilee…to account.”

Internal divisions have weakened the coalition, Mr Ondabu said. At a political rally in September in Kenya’s eastern Machakos County, Wiper’s Mr Musyoka accused other CORD leaders, whom he did not name, of being agents for the ruling Jubilee coalition. Meanwhile CORD is split between young leaders and the old guard, which includes Mr Odinga, 69, and Mr Musyoka, 60.

Opposition parties “play the important role of shadowing government and proposing alternative strategies for management of public affairs,” said Kamotho Waiganjo, a commissioner at the Commission for the Implementation of the Constitution (CIC), a Nairobi-based government body.

But CORD has tabled only one motion before Parliament in the last year, one seeking to impeach the internal security cabinet secretary, after a series of deadly incidents linked to Islamist militants the Shabab, including the Westgate Mall attack in 2013 that left more than 67 people dead. The impeachment motion was withdrawn two days later under unclear circumstances.

During Mr Odinga’s three-month stay in the United States earlier this year, the coalition failed to present an alternative budget for the 2014-15 financial year, which is customary for the Kenyan opposition.

A well-thought-out shadow budget would have helped CORD regain its footing, said Kenyan-born Mohamed Wehliye, senior vice president at Riyad Bank in Saudi Arabia. “It would have swayed Kenyans [into thinking] that the opposition is alive. It would also have painted a positive picture of an opposition that not only criticises the government but is also ready to provide…solutions to address poor health care, insecurity and unemployment.”

Mr Odinga denies his party has lost relevance. He blames the new constitution for CORD’s perceived weakness. This new framework document, adopted in August 2010, altered the traditional roles of the opposition by barring a presidential candidate and his running mate from sitting as members of Parliament (MPs).

This means that neither Mr Odinga nor Mr Musyoka can head critical parliamentary committees such as the Public Accounts Committee (PAC), which has customarily been headed by the opposition leader. Ababu Namwamba, of Mr Odinga’s ODM party, is the current PAC leader. Most Kenyan commentators, however, view him as a pale shadow of Mr Odinga and other past PAC chairs such as Mr Kibaki and Mr Kenyatta.

CORD’s performance is par for the course: leaders promising to turn over a new, more democratic leaf have routinely disappointed citizens of this east African country.

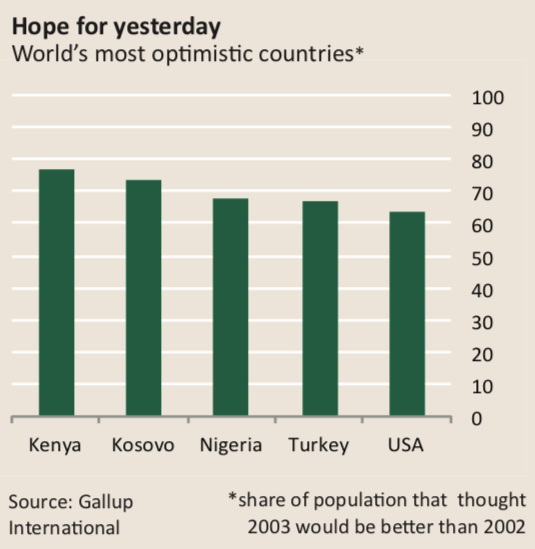

In 2002, for example, Kenyans were the most optimistic people in the world, according to a Gallup International poll of 65 countries that year. This was one month before the January 2003 election in which Mr Kibaki’s National Rainbow Coalition defeated the Kenya African National Union (KANU), which had ruled Kenya for 39 years.

Regrettably, the optimism—based on the promise of open elections, free media and organised civil society—was short-lived. Mr Kibaki’s regime became quickly engulfed in high-level cases of corruption and greed, including the Anglo Leasing scandal and the $98.7m Triton oil theft, among many others. This was coupled with a crackdown on media freedom.

“Opposition politics was practically dead then,” said Edward Kisiang’ani, a politics professor at Kenyatta University. Mr Kenyatta, then the leader of KANU, the official opposition party, chose not to check government operations, Mr Kisiang’ani said. “It was a well-calculated tactic to support one of their own,” he said, explaining that that Mr Kibaki and Mr Kenyatta are both Kikuyu, Kenya’s dominant ethnic group.

Mr Kenyatta’s strategy succeeded in the 2013 elections: Mr Kibaki supported Mr Kenyatta to become Kenya’s fourth president.

Kenyans are once again paying a heavy price for the lack of opposition. “Political opposition plays a…critical role in checking government excesses,” said the CIC’s Mr Waiganjo.

But this countervailing force is missing and Mr Kenyatta’s government has been implicated in several corruption scandals. These include the $3.7 billion standard gauge railway controversy and the $279.5 million school laptops tender. For Kenyans it brings back unwanted memories of the sleaze that stained the Moi and Kibaki administrations.

Kenya’s next elections are scheduled for August 8th 2017. Mr Odinga needs to change tack for his party to become a relevant force again. He needs to show how CORD could tackle Kenya’s crucial problems: terrorism, food insecurity and high unemployment.

He also needs to delegate party operations to youthful party leaders such as MP Tawfiq Ababu Namwamba, 39, and Ali Hassan Joho, 38, the governor of Mombasa County. These young Turks can compete effectively with the youthful Mr Kenyatta, 53, and his equally dynamic deputy William Ruto, 47.

Finally, Mr Odinga must act to transform CORD into a truly national organisation. Kenyans perceive the party as a collective of his Luo tribe, controlled by Mr Odinga’s relatives such as his cousin, Jakoyo Midiwo, the party’s chief whip.

If Mr Odinga does not make these moves, the coalition does not stand a chance and competitive politics in Kenya will remain weak. The question is: does the old campaigner have any fight left in him?