Rwanda: dictatorship and donor darling

by Daniel Howden

Jaqueline Mukagatete lives somewhere between Rwanda’s past and its future. She shells peas while sitting on the step of what will be, when it is finished, her new concrete house. Only a stone’s throw away is the traditional mud-and-wattle hut where she still sleeps at night. The 32-year-old mother of four says she is proud of the new home and eager to start a new life.

The Mukagatetes are among 100 families who have moved to the Kitazigurwa-Ntebe (model village), a two-hour drive outside of Rwanda’s capital, Kigali. It is one of several similar collective villages in the small mountainous central African state. They are intended to help families escape the poverty trap in a single generation. Smallholders have been scraping a living in subsistence farming for years; their tiny plots are spread out over the surrounding hills. Now, they live in identical houses lining the streets of these new villages. Each one has a small lawn outside and a naked electric light bulb hanging from a cord inside.

Projects like this model village, only a mile away from the rural home of President Paul Kagame, are emblematic of the regimented, aid-intensive route Rwanda has taken to development. It is a strategy that has enjoyed considerable support from the Unites States, Britain and other major donors. Rwanda until last year depended on aid equivalent to more than 40% of its budget.

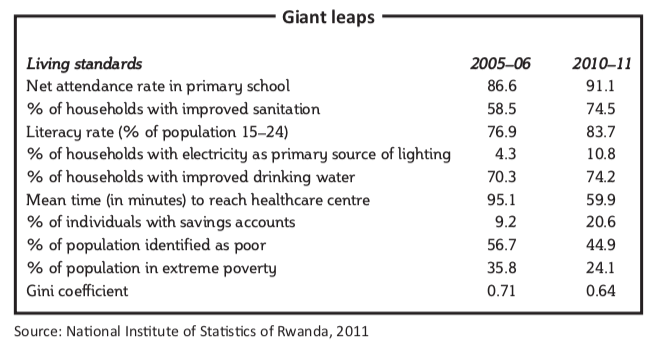

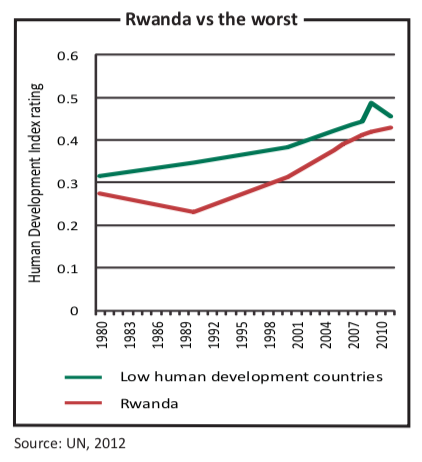

The results have been remarkable. Development experts have feted the country for achieving what they call the “hat-trick”: rapid growth, sharp poverty reduction and reduced inequality, but that compact is now threatened by international condemnation of Rwanda’s interference in its vast and chaotic neighbour, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Kagame’s government has steadfastly denied a United Nations (UN) report that concludes that it commands, recruits and finances armed rebels in the eastern DRC. Those denials have failed to stop a backlash from donors, led by Britain which, after internal wrangles, froze its aid budget last year. Other European Union countries have followed suit and only the US has restricted itself to a symbolic cut in military assistance of $200,000.

Rwanda has capitalised on guilt over international failures during the 1994 genocide — when about 800,000 people were murdered in three months — to earn aid dollars and plaudits. But this recent sudden shift in perceptions has surprised long-term observers and raised concerns that development lessons learned in Rwanda will be discarded.

Rwanda is starkly different from its east and central African neighbours and sometimes appears to be a giant laboratory for development studies. Nothing symbolises the ambition and speed of the country’s modernisation effort more than the Kivuwatt project on Lake Kivu, the deep and dangerous body of water that divides Rwanda from the eastern DRC.

Kivu is one of the world’s three exploding lakes, saturated with carbon dioxide and methane from surrounding volcanoes. An explosion in which the lake’s gases are suddenly released, what scientists call a “turnover”, would be “the biggest catastrophe humankind has experienced”, according to Finnish engineer Jarmo Gummerus, who is working on the power project. The gases would either suffocate or incinerate the two million people living on the lake’s shores.

The solution has been to build a hi-tech barge weighed down with gleaming steel tanks that now sits in the bay at Kibuye, on the Rwandan side. When it is finished the project will extract the methane and convert it into electricity. With a contract from the Rwandan government, the US-based energy company Contour Global is building the plant, which is paid for by loans from development banks and private investors.

The ambition of the first phase of the Kivuwatt project may yet represent the high watermark for Rwanda’s development push. When it is switched on later this year, the $140 million project will increase the nation’s power generation by a third.

Its 11 milion inhabitants make Rwanda the second most densely populated nation in sub-Saharan Africa and it faces a huge challenge to feed itself. The government has responded by terracing the “land of a thousand hills” on an epic scale. Totemic policies like a ban on plastic bags mean that its rivers and drainage ditches are not choked, unlike their counterparts in Uganda and Burundi.

Some of the biggest achievements from Rwanda’s development laboratory have come through direct budget support: aid that goes to the government, rather than NGOs — an approach donors favour in countries where government corruption is rife.

Rwanda is on course to meet the UN’s global anti-poverty targets, the Millennium Development Goals. In education, for instance, foreign aid has financed new schools, trained teachers, developed learning materials and improved access. A recent report by the Overseas Development Institute found that budget support had met government and donor objectives and had been “extremely positive”.

These kinds of results have made the country a “donor darling” and a vital proving ground in the debate over whether foreign aid works. It was the star performer in Britain’s Department for International Development (DfID) annual report in 2012 after receiving $112 million that year. The report card highlighted a surge in primary school enrolments; a sharp drop in the population living below the poverty line; and a near doubling in the number of births attended by a skilled midwife. Only one line in the report mentioned the need for a “transition to inclusive politics and enhanced human rights”.

A senior western diplomat warns that the fallout from eastern Congo has ruptured donor relations with Kigali, saying that “Rwanda’s relationship with the rest of the world has changed”. The cost of that change is measurable: Rwanda’s finance ministry expects GDP growth, previously forecast to rise to 7.8% in 2013, to be 1.5 percentage points lower. Inflation, which had crept up to 6.6%, is expected to rise even higher. Foreign currency shortages in Kigali have created a small black market there for the first time since 1994.

Meanwhile, the vision of transforming a subsistence farming economy into a middle-income services hub by 2020 — based on annual growth of 11% — is fading. Rwanda’s Cuban- style health system with 90% coverage is creaking. Bonuses to doctors and nurses worth up to 40% of their salaries have already been cut, due to the suspension of aid.

For the architects of Rwanda’s aid-driven accomplishments, like the respected governor of the Central Bank, Claver Gatete, the suspension of committed funds is a betrayal. A model based on direct budget support, developed with Britain, was close to making Rwanda an “aid graduate” that could have taught other poor countries how to develop. Without that aid, he says, this is “no longer a guarantee”. The ability to make the best use of it has also gone.

The signal being sent to multilateral donors and lenders is as important as the money at issue, he argues. The World Bank, the IMF and the African Development Bank have all delayed significant funding decisions until a clearer signal emerges from the US and the EU.

Gatete, a former ambassador to the UK, summed up the consternation felt by his compatriots with three questions: Are there poor people in Rwanda? Did the money reach them? Did any of it go missing? He answers the first two questions with “yes”. The third answer is “no”.

There is also considerable surprise among Rwanda’s fledgling opposition that the aid tap has been turned off because of events in the DRC rather than repression at home. Foreign critics point to the complete absence of a free media and the prohibition of credible opposition groups as evidence that donors are supporting a dictatorship in Rwanda. (So far, the aid cut-off has not reduced the fighting in the DRC, but it may have encouraged the on-going talks.)

Victoire Ingabire, who tried to challenge Kagame at the last election in 2010, was recently jailed for eight years on charges that included “genocide denial”. Other party leaders admit to “looking over their shoulder” and avoid criticising the government directly.

In a report advising the Commonwealth against admitting Rwanda four years ago, respected Kenyan scholar Yash Pal Ghai said the country was not a state with an army but “an army with a state”.

One of the responses to the aid shortfall has been the new Agaciro (Dignity) Fund, similar to a war bond, which relies on voluntary contributions. In its first two weeks of operations last year it raised $11.7m. But this fund cannot replace aid, as it is effectively a tax on public sector pay. This one-off act of defiance will be felt in reduced consumer spending and does not inject money into the economy. China has also provided soft loans worth $36m but neither will adequately replace larger western aid flows.

In Mukagatete’s model village there is disciplined determination to look forward. “We can never go back to how we were,” she says. “My children will not live how we have lived. People are told to put in decorative plants and instructed to grow kitchen gardens. All residents are expected to work on their own homes as well as the construction of new ones. For all the collectivism, houses still cost between $7,500 and $10,500 to build. That money is going to be harder to find in the new, harsher aid climate.