Southern Africa’s telecoms

New undersea cables: Not enough to kick-start a tech revolution

by Simon Allison

It is easy to forget in this digital age, but the world wide web is exactly what it sounds like—a planet-spanning tangle of wires and cables through which all our online activity travels. These cables climb up mountains and burrow through tunnels; they are buried deep under the sea and beneath our homes.

They require constant maintenance and upgrading to keep the electronic signals flowing as fast as possible. Without interference or traffic, electronic data can travel at the speed of light. This is how an e-mail can cross continents and land in your inbox faster than you can press the refresh button.

Even the wireless miracle that is mobile data relies on physical infrastructure to connect the mobile towers to the global communications network. The same applies to satellite internet; the satellite merely acts as a connection to a place that can access the rest of the web via cables. About 95% of all intercontinental internet traffic travels via submarine cables, not satellites, according to Fierce Telecom, an online newsletter that tracks the telecoms industry.

Internet, in other words, is only as good as the cables through which it flows.

Imagine then, southern Africa’s excitement when it was announced over the course of the last year that the region could expect not just one new, high-capacity, high-volume undersea fibre-optic data cable in the near future, but three or four. Collectively these cables could triple the region’s existing capacity.

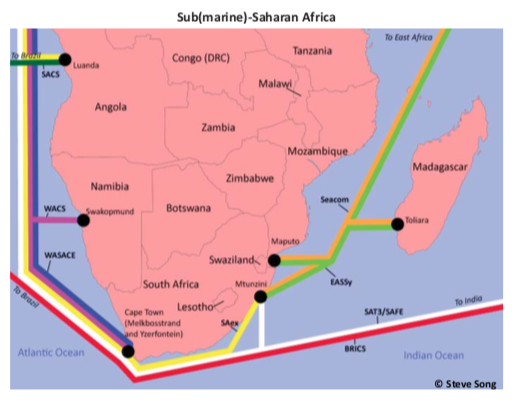

The South Atlantic Express (SAex) cable will link South Africa with Brazil at a speed of 12.8 terabits per second; the Wasace Cable Company (WASACE) has a line on the same route, with extensions to Angola and Nigeria at 40 terabits per second. Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) may be connected with a 12.8 terabits per second link. The South Atlantic Cable System (SACS) will run between Angola and Brazil at 40 terabits per second.

If built—and this is a big if—these will complement the broadband cables already online in the region: the East African Submarine System Cable (EASSy), the West African Cable System (WACS) and Seacom.

Completed in 2009, Seacom was the first high-speed broadband cable to connect southern Africa, tripling the capacity provided by the painfully slow South Atlantic 3/West Africa Submarine Cable/South Africa Far East cable system (SAT-3/ WASC/SAFE)—an upgraded version of a system first laid in the 1960s. With Seacom and the East and West African cable systems it is now possible for southern Africans to connect to the web at speeds comparable (if not quite yet equal) to those in existence in Asia, Europe and North America.

Are these proposed four new cables really needed? The current ones should be enough for the region, according to Mark Simpson, Seacom CEO. “There are effectively four different cable systems [the three broadband lines plus SAT-3/WASC/SAFE] with plenty of capacity and much more in terms of potential capacity,” he told Africa in Fact.

Mr Simpson is far from convinced that the new undersea cables will make a significant difference: “Whilst some of these new cables will no doubt continue to change the supply situation which will reduce the cost of international capacity, I don’t think they’ll have a big impact on the vast majority of users in southern Africa; most costs are domestic rather than international.” In other words, the factors driving up the cost of broadband in southern Africa mostly come from domestic issues such as poor national grids, rather than any limitations on connections to the outside world.

Mr Simpson is biased: He heads a company whose revenue is threatened by competition and building cables requires spending vast amounts of money that needs to be recouped. “These are massive capital investments,” he said. “Depending on how long the cable is and what type of cable is used, it can run into hundreds of millions of dollars.” Seacom is making good returns, but it will be decades before it recovers its initial investment because the physical and economic lifespan of any undersea cable project averages 25 years, he explained.

However, Mr Simpson is not alone in questioning the need for the new undersea cables. Arthur Goldstuck, a South African information and communications technology (ICT) industry analyst, agreed with the Seacom chief executive: southern Africa has still not taken advantage of the existing broadband capacity.

“For the first time, we have a very well-developed undersea cable infrastructure,” said Mr Goldstuck, who is also the editor of Gadget magazine. “The need for new cables is nothing like it would have been a few years ago.”

The problem lies not in too little capacity but in fragmented connectivity. Most undersea cables coming into southern Africa connect either at Mtunzini on South Africa’s Indian Ocean coast, or at Yzerfontein on the Atlantic. This is where the bottleneck begins. Once the cables hit the coast, they still need to get into homes and businesses across the region. This requires a domestic network of cables and connections.

In South Africa, great strides have been made in building a national fibre-optic grid, but even this is not enough. These lines have not reached the “last mile” or the actual physical connection to the home or business.

This is taking far longer than it should because Telkom, the state telecoms operator, is in sole charge of the last mile. Ordinary consumers often wait months to get the necessary lines installed. This problem is even worse in other countries in the region, where a poor national infrastructure beyond the big cities means last mile connections are not even possible. In Zambia, for instance, most safari lodges (which bring in a hefty chunk of that country’s vital tourism revenue) are forced to rely on unreliable satellite internet connectivity, even when they are near metropolitan areas, because there is simply no other option.

This missing groundwork has indisputably slowed down the adoption of fixed- line broadband. In South Africa, the numbers speak for themselves: fewer than 900,000 fixed-line subscribers, with just one operator (other operators simply rent space on Telkom’s lines), according to World Wide Worx, a technology research firm based in South Africa. Conversely, there are more than 6m mobile data subscribers, with six operators in the market, even though mobile data is substantially slower.

There is a solution for South Africa, but it requires government intervention. “Fundamentally, the biggest issue holding back access is the slow pace of the regulatory process,” Mr Goldstuck said. This requires the communications department to provide guidelines to the regulator, the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa. “If the policy directives aren’t forthcoming, then regulatory advancement is not forthcoming,” he added.

The first move would be to remove Telkom’s monopoly over the fixed-line network. Strong regulatory policy is also required on other issues such as local loop unbundling, which would give other providers direct access to Telkom’s exchanges; and better management of the electromagnetic spectrum on which wireless, radio and TV signals are broadcast.

One example illustrates the point: the International Telecommunication Union has set 2015 as the deadline by which all countries must switch to digital as opposed to analogue broadcast signals. South Africa will miss this deadline, thanks largely to the inertia and incompetence of the communications department, which has not drawn up the details of how and when this should happen.

The country will pay a price for this delay: the so-called “digital dividend”— the narrower and more efficient spectrum range that becomes available once the switch is made. It is ideal for the latest fourth-generation or Long Term Evolution wireless cellular signal.

If the switch to digital is not made, the development of mobile internet in South Africa will almost certainly fall behind the rest of the world.

Ultimately, the lesson of southern Africa’s potential new undersea cables is this: although they could dramatically increase the region’s broadband capacity, that prospect will remain unrealised until governments implement policies that recognise the importance—the necessity, even—of keeping pace with the global digital revolution.

“Affordable access is no longer a luxury,” said Steve Song, an advocate for better connectivity in Africa. “It is a tide that raises all ships,” he said. “It creates efficiencies at every level from the rural farmer to the large corporation. It can facilitate better governance through better communication and increased transparency. It can enable better healthcare, better education, better services all round. And perhaps most importantly it opens to the doors to innovation, to new ideas and new opportunities for everyone.”