Mobile technology: moving past the gatekeepers

by Gavin Davis

Opposition parties in Africa have struggled for decades in a media environment that favours incumbents. Of 54 African countries measured in the Freedom House 2012 press freedom index, only five were considered to be “free”. Press censorship and pliant public broadcasters mean that elections can be fixed before the first vote is counted.

State control of the media is not the only hurdle preventing parties from getting their message to the electorate. Many face the invidious choice of either giving journalists “petrol money” or having their press conference ignored. “It’s a pity that, as the party advocating for a corruption-free society, we find ourselves embroiled in this vice,” says Kasekende Bashir of the Liberal Democratic Transparency (LDT) party in Uganda.

Social media have the power to change all this by permitting parties to bypass the gatekeepers — reporters, editors and government officials — who shape or control the press agenda. The Arab Spring in 2010–11 revealed how social networks such as Twitter, Facebook and YouTube revolutionised political communication in North Africa.

In Africa only about 16% of the population have internet access — less than half of the world average of 34%, according to Internet World Stats, an online demography site. A shortage of electricity and broadband infrastructure, coupled with the high cost of hardware to access the internet, mean that most African countries find themselves on the wrong side of the global digital divide.

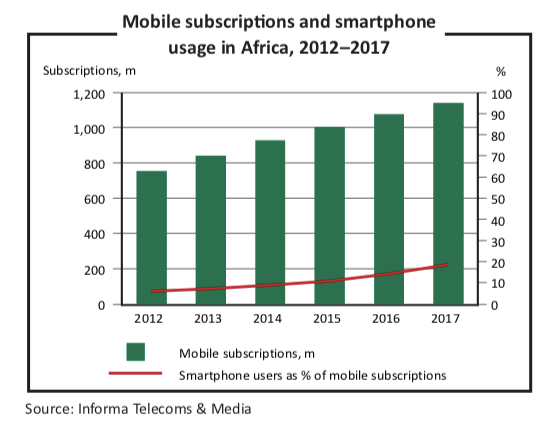

The good news is that a mobile revolution is sweeping the continent and bridging this gap. More Africans have access to a mobile phone than clean drinking water, according to Jan Hutton, telecoms director at Nielsen, a market-research firm. After Asia, Africa is the world’s largest mobile phone market, with 700 million mobile connections. By 2016 there will be one billion — a mobile phone for nearly every person, according to a 2012 report by financial services firms Frontier Advisory and Deloitte.

While not every mobile phone has social networking capabilities, this is changing too. At the end of 2012, smartphone users accounted for 6% of Africa’s total mobile subscriptions; this share is forecast to rise to 18% by 2017, according to Thecla Mbongue, a senior analyst at Informa Telecoms and Media, a market-research firm.

Once mobile take-up reaches critical mass, social media may well become the only game in town. Many political parties realise that they need to be ahead of the game now if they are to win votes in the future. At a conference on political communication held in Cape Town in November 2012, opposition parties from the Seychelles to South Sudan highlighted the rising significance of social media in their communications strategies. All agreed that starting the right conversations on social media and steering engaged followers in the right direction are the keys to future success. These online conversations among many individuals are gradually supplanting the one-way “broadcast model” of communications.

In Botswana voters no longer trust the media and are turning to social networks for their news, reports Winfred Rasina, spokesman for the Botswana Movement for Democracy (BMD). He spends an average of two-and-a-half hours daily updating the BMD’s Facebook page and interacting with potential voters. Only 7% of its citizens access the internet, according to the International Telecommunication Union. But “Botswana has a population of only 2 million people, which means that word of mouth travels quickly,” he says.

Trust in traditional media is in decline, particularly among the youth, says Fungisai Sithole, chief of staff of the Movement for Democratic Change in Zimbabwe. “The current generation does not want to be treated as the ‘other’. They want to be engaged, they want to talk, they want to contribute,” she says. To get around the drawback of low internet access and the high cost of smartphones, the party has developed a bespoke platform that uses text messages to interact with voters and members.

Another party finding innovative ways to reach the electorate is the Civic United Front (CUF) in Tanzania. It has linked its social media platforms with popular youth websites and trained a team of young activists to respond to issues. Abdul Kambaya, CUF’s national director for publicity, says that the success of this strategy is evident from the response it has elicited from its opponents: the party’s website was hacked and completely destroyed six months ago.

This is a cautionary tale. As more people begin to use social media for political engagement, so too will governments increase their efforts to curtail it (see page 13). Finding ways to circumvent state censorship with sophisticated social media strategies will be a key objective for African opposition parties in the years ahead.

The mobile revolution is a potential game-changer in Africa, where media gate-keepers have exerted too much power for too long. Once the social media groundswell breaks, a political tipping point may well follow.