Sudan’s Blue Nile and South Kordofan rebels

After losing South Sudan, the country is disintegrating into a series of warring regions

The provinces of Blue Nile and South Kordofan in remote southern Sudan are war zones. They are also the scene of an impending health emergency: the government of neighbouring South Sudan confirmed last September the appearance of three cases of polio,a dreaded disease which leaves infected children paralysed.

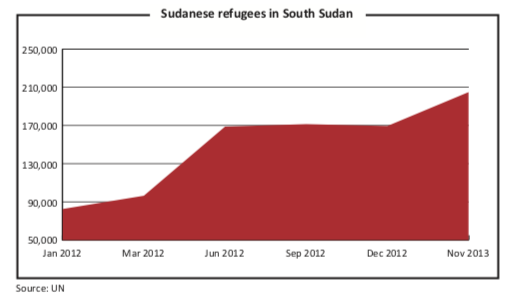

Trying to vaccinate these children and their families is even more difficult as two years of fighting have driven more than a million people from their homes, according to the United Nations. Most are now internally displaced. Some seek refuge inside the Nuba Mountain’s caves and beneath its boulders. Over 190,000 people have crossed into newly-independent South Sudan, according to the UN’s refugee agency.

Sudan has been embroiled in a several prolonged civil wars almost continuously since independence from the UK in 1956. These conflicts are rooted in the Muslim north’s economic, political and social domination of the largely African, non-Muslim, non-Arab southern Sudanese. Peace talks culminated in the signing of a North/South Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005 and led to a referendum and South Sudan’s independence on July 9th 2011.

When the lines were drawn dividing the two countries, the people of South Kordofan and Blue Nile states found themselves assigned to Sudan in the north. As Khartoum attempted to exert its control over what had been rebel held-areas for many years, tensions escalated.

Armed skirmishes broke out in early June 2011, a month before South Sudan’s independence. The old rebel movement – the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), of the late Dr John Garang, was reformed and renamed. This time it was called the SPLM-North (SPLM-N). Led by Malik Agar, it is fighting in both Blue Nile and South Kordofan, provinces just north of South Sudan.

The authoritative Swiss-based Small Arms Survey concludes that the rebels control large areas of these provinces. The SPLM-North with its 30,000 troops is allied with the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), based in the western Sudanese region of Darfur. Some 700 – 1,000 experienced JEM fighters are said to have been critical to rebel successes in recent battles. Although the south supplied the rebels with troops and large quantities of tanks, artillery and other equipment just before it gained independence in 2011, the Small Arms Survey report maintains that it “has found no evidence of weapons supplies from the Government of South Sudan (GoSS) to the SPLM-N, though some political and logistical support is evident.”

If South Sudan is not providing support to the rebels, it is unquestionably assisting about 190,000 refugees who have sought sanctuary on its soil. The villagers from South Kordofan’s Nuba Mountains make the hazardous journey to Yida refugee camp, which is just inside South Sudan. This camp, situated among thorn trees, was designed to hold around 20,000 people. Today some 70,000 are living there.

When the rains arrive the camp becomes almost inaccessible from the ground – cut off from the rest of the world by vast ponds of stagnant water. Only careful pre-positioning of stocks has allowed the UN’s refugee agency, the UNHCR, to provide for such huge numbers.

The agency has attempted for several years to move the refugees away from Yida, a refugee camp within easy walking distance of Sudan. (Alternative arrangements have been made about 30km from the border.) The Sudanese air force has bombed the camp, which is pitted with holes into which the refugees cram when a plane is heard overhead. Despite being in such a vulnerable location and difficult to supply, the residents – mostly women and children – are reluctant to leave for safe havens further inside South Sudan. They meet their fathers and brothers, who take intermittent breaks from fighting on the frontline, in the tea shops and cafes that dot this camp. Although the SPLM-North is not meant to cross the border in uniform, it is not uncommon to see fighters sipping drinks with rifles resting across their knees.

If Sudan’s president, Omar al-Bashir, had no more than the SPLM-North to worry about he would probably rest assured. But the alienation of the Sudanese is much wider. Not only is the conflict in Darfur persistent, there is also discontent in Sudan’s east and far north, towards the Egyptian border. A long-held policy of favouring the population living along the Nile valley over the rest of the country has stoked this discontent.

The people living here, near and just north of Khartoum, once enjoyed the bulk of Sudan’s oil revenues, which peaked in 2010 as most of the oil-fields came on stream, according to the US Energy Information Administration. But South Sudan’s independence a year later has deprived Khartoum of much of this oil. Since then, bickering between the two countries has reduced the north’s oil income still further. Oil represented 57% of Sudan’s total government revenues and 78% of its export earnings in 2011. The loss of this income has hit the Khartoum government hard.

In recent weeks the patience of the Sudanese has been tested even further. The government cut fuel subsidies at the end of August, doubling the prices of kerosene on which most people depend to do their cooking. The costs of transport and essential foods also rose.

The measures were imposed after pressure from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, which argued that fuel subsidies skewed government spending. The IMF estimated the subsidy cost 12 billion Sudanese pounds ($2.27 billion). It argued that up to three-quarters of all tax went to pay for the subsidy, which disproportionately favoured the rich and led to smuggling across the country’s borders.

People took to the streets, often led by students, demanding the removal of the president. But Mr al-Bashir, who has governed the country since he overthrew Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi in a bloodless coup in June 1989, was not so easily dislodged. The al-Bashir government responded with tear gas and live ammunition killing, from 50 to as high as 200 people and wounding about 1,000 demonstrators. Hundreds more were arrested.

Sudan’s most popular newspaper Al-Intibaha was closed, as were the offices of the satellite channels Al-Arabiya and Sky News Arabia. The internet was cut, to prevent word of the protests spreading. The notorious “Central Reserve Police”, drawn from some of the poorest villages and fiercely loyal to Mr al-Bashir, were unleashed onto the streets. Driving around in four-wheel drives, known locally as “Thatchers” after Britain’s former prime minister, the Iron Lady, they dealt ruthlessly with the protesters.

So far the tactic has paid off. Calm has returned to Khartoum. But with a spreading war in the south and simmering unrest across much of the rest of the country, it remains to be seen how long the authorities can contain the opposition. Mr al-Bashir has used oil revenues to fracture his opponents and their divisions are keeping his regime in power. At best Sudan remains an unstable regime. At worst it could collapse into a series of warring regions. Somalia, which has struggled without a stable government since 1991, remains the example for all to observe.

In the meantime, a polio outbreak in Somalia may be spreading to Sudan. Health workers need a ceasefire before they can move out across the mountains and plains of southern Sudan. Ali Al-Za’tari, the UN humanitarian co-ordinator in Khartoum, announced that the Sudanese government would unilaterally stop hostilities between November 1st and the 14th to allow the vaccination campaign to go ahead.

But Yassir Arman, spokesman for the SPLM-N, disagreed. “We need to sit down with Khartoum and agree on the modalities of the ceasefire. Only then can we persuade our people to come out of hiding in the remote areas, and allow their children to be vaccinated.”

The rebels are also asking for the UN troops in the contested border area of Abyei to transport the vaccines from Norway. “Our people just don’t believe that the Sudan government, which is trying to kill them, can also bring medicines to save their children,” explained the rebel spokesman.

A long-running dispute over Abyei, an oil hub on the border claimed by both sides, will be still harder to solve. UN peacekeepers, dampening the tension, will be needed for the foreseeable future. Sudan has ominously referred to Abyei as “our Kashmir”, referring to the decades-long border dispute that has divided India and Pakistan, once a unified country, and now China. At least five other areas along the border are disputed. But both sides are waiting for a report from an African Union panel. If need be, they have agreed to go to international arbitration.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]Martin Pabst is a political scientist and freelance researcher based in Munich. He is a regular contributor to German-language journals such Austrian Military Journal, European Security & Technology, S+F – Security and Peace. He researched in the Western Sahara, at MINURSO and in the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria. [/author_info] [/author]