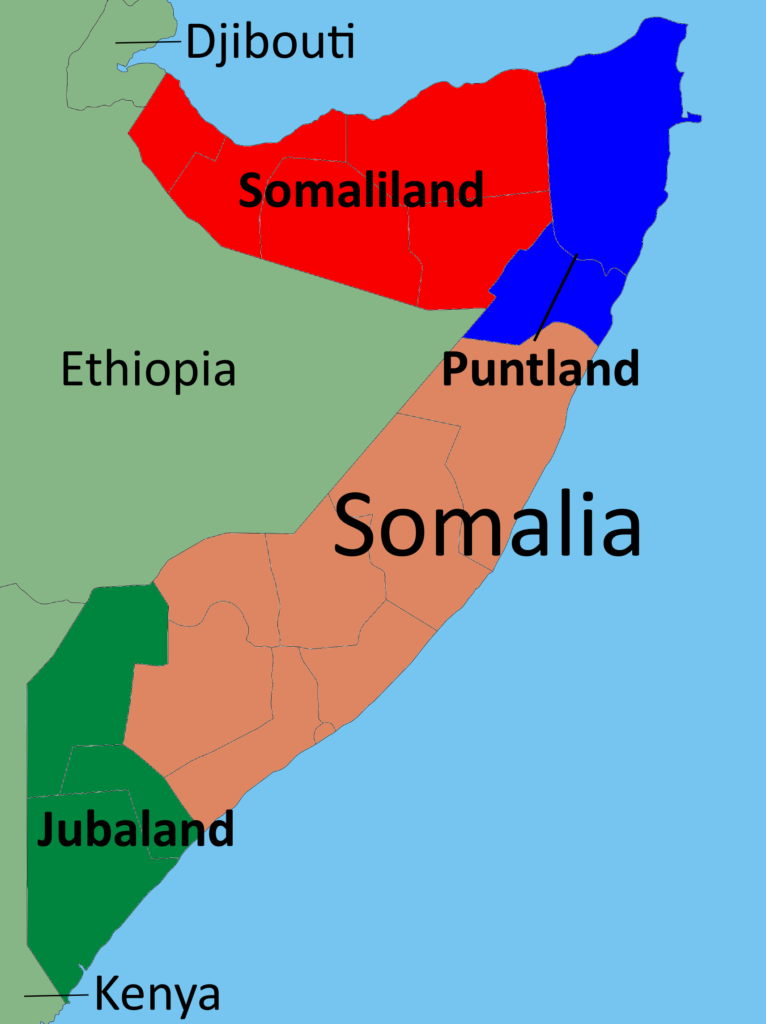

Horn of Africa: Somalia, Somaliland, Puntland and Jubaland

Three regions in Somalia seek independence or autonomy

For a country that does not exist, Somaliland does a remarkably good job of pretending.

It has a green, red and white-striped flag, a foot-tapping national anthem, and a bustling capital city, Hargeisa. Its administrative district contains ministries, a central bank and even a presidential palace. Its government is fully self-governing. Its 3.4m residents elect the president and legislative assembly in polls (The last general election was held in June 2010.) that are relatively free and fair. They show their Somaliland passports when crossing borders, although only neighbouring Djibouti and Ethiopia accept it as a valid travel document. And pay for goods with Somaliland shillings. They vigorously celebrate Somaliland Independence Day each May 18th. Their own police force, coast guard and army protect them, if need be.

Above all, Somaliland boasts peace, stability, and a basic respect for the rule of law – the foundations upon which all modern states are built.

Somaliland has all the trappings of a real country. But it is not.

It is, under international law, a semi-autonomous region of the Republic of Somalia, measuring approximately 137,600 square kilometres (a little larger than Malawi or England). It is theoretically answerable to the government of Mogadishu, Somalia’s capital. Somaliland, however, has refused point-blank to heed that call since its unilateral declaration of independence in 1991. It is perhaps the best organised and most successful secessionist movement in the world.

It should come as no surprise that various regions within Somalia have stopped relying on the central government. Somalia is, after all, number one on the failed-states indexproduced by Foreign Policymagazine and the Fund for Peace, a research organisation. For the last two decades, it has been engulfed by civil war and foreign military interventions. Even now, Mogadishu is in physical control of just a small percentage of the country, thanks to the thousands of soldiers involved in the African Union Mission in Somalia.

In the absence of a functional central government, many within Somalia’s borders have improvised their own governance. In some places, clan structures have filled the void left by the state; in others, the ideology and structure offered by Islamist groups such as the Shabab have provided a modicum of normality. Still others have formed their own civil administrations, running a government in parallel to the one in Mogadishu. Of these, Somaliland, in north-west Somalia, was the first and continues to be the most successful, by far.

This makes a certain amount of sense. The borders of Somaliland today are roughly analogous to those of British Somaliland, a territory carved out by British colonialists in 1888. There was also French Somaliland, which is modern-day Djibouti; and Italian Somaliland, corresponding to south-central Somalia. In 1960, a newly-independent British Somaliland voted to join up with Italian Somaliland to form the union of Somalia; French Somaliland, perhaps wisely, declined.

Somaliland, in other words, has a track record as an independent entity. Mogadishu has not always ruled it and when the union started to sour, it simply opted out. This, at least, is the argument put forward by the administration in Hargeisa. Mogadishu maintains that the union was not an opt-out deal and very much remains in force.

It is worth noting here that when the union split, Somaliland suffered the very worst of former dictator Mohamed Siad Barre’s excesses.

“The people of Somaliland and the elites there have legitimate reasons against the previous Somali government of Mohamed Siad Barre, the previous regime that is, which really levelled cities like Hargeisa to the ground and killed hundreds of thousands of people in the space of two years, 1988-1989,” explained Abdi Aynte, a former Al Jazeera journalist who recently established the Heritage Institute in Mogadishu, Somalia’s first independent think-tank. The devastating assault, orchestrated by Mr Barre from Mogadishu as he tried and ultimately failed to consolidate his power, remains central to Somaliland’s determination to separate from Mogadishu. No area of Somalia escaped unscathed from Mr Barre’s unstable autocracy, Mr Aynte pointed out. Even Hargeisa’s souvenir shops sell “Somaliland genocide” postcards.

Since then, in relative terms, Somaliland has prospered while the rest of Somalia has disintegrated. It is a success story in a land where achievements are few and far between, although its ultimate goal—of genuine, globally-recognised independence—remains as elusive as ever.

The wannabe nation

Somaliland may have a genuine case for legal recognition. “There are no legal barriers to Somaliland’s independence,” argues Casey Kuhlman, the American head of Watershed Legal, Somaliland’s first and only private law firm. “Somaliland has long met the Montevideo criteria for statehood. It also meets the non-legal but relevant African Union criteria for independence.”

Article 1 of the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, which forms the basis of the classic definition of modern statehood, declared that a state should possess a permanent population, a defined territory, a government and the ability to enter into relations with the other states. Somaliland ticks these boxes.

As for the African Union, Somaliland satisfies the controversial convention that Africa’s borders should by and large mirror those existing at the end of the colonial era. British Somaliland was, after all, a political entity separate from Italian Somaliland.

Legalities, however, do not tell the whole story. The real opposition is political and the little wannabe country is up against powerful foes.

Most obviously, Somalia, its mother country. It is not particularly interested in losing territory that officially belongs to it, especially as Somaliland represents one of the few areas within Somalia’s borders that works. Few official figures exist on Somaliland’s economy, but a 2006 World Bank Report said its GDP was $1.3 billion, with 65% generated by agriculture and livestock. (The only sheep that can be slaughtered in Mecca come from Somaliland, as it is a special breed favoured by the Prophet back in the day.) There is a sense among some Somalis that Somaliland should be trying to spread its peace and stability through the rest of the country, rather than seeking to separate itself. “Many people in south central Somalia feel that Somaliland has done extraordinarily well, and that instead of helping and assisting their brothers to the south they are just running away from the fire instead of contributing in [sic] putting out that fire,” Mr Aynte observed.

For Somalia’s federal government, Somaliland’s independence is not even up for discussion. In the wake of recent, very tentative talks between Somalia and Somaliland in Istanbul in July, Somalia’s President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud expressed his position in no uncertain terms in a statement to Somali media: “With the good offices of the government of Turkey, we have continued our dialogue with the authorities in Somaliland, underscoring our determination to preserve the unity of the country, not by force and coercion, but through dialogue.”

But Somaliland faces a far larger obstacle in the form of the African Union. Its members worry that recognising Somaliland could reinvigorate secessionist movements within their own countries. “The African Union detests the idea of secessions because it opens a can of worms for them,” Mr Aynte said. The first and only time the issue of Somaliland was brought formally before the African Union was in November2005 during a meeting of the Peace and Security Council, the AU body responsible for solving and preventing conflict. The commissioners at that meeting quietly shelved the issue. It has not been seriously considered since.

African Union recognition is vital, because it also determines the international community’s response. The United States, the United Nations and the European Union have all said they would be willing to consider Somaliland’s independence, but only if the African Union does so first.

Somaliland’s struggles for international recognition have informed the political direction of other semi-autonomous entities within Somalia, most notably Puntland. Located in northern Somalia, just east of Somaliland, Puntland has also created its own governance infrastructure, declaring its autonomy in 1998 following a conference of political elites, tribal elders, business leaders and civil society representatives which sought relief from the on-going civil war. Like Somaliland, it is to all intents and purposes an independent state. Unlike Somaliland, it even has its own air force. But – mindful of Somaliland’s failures in this regard – Puntland has never sought or claimed to be independent. It is not, strictly speaking, a secessionist movement, although it maintains complete control over its internal affairs.

This paradox was neatly illustrated in October, when Puntland’s government abruptly cut ties with Mogadishu. “Puntland will suspend all cooperation and relations with Somali Federal Government until the country’s genuine federal constitution is restored,” said Abdirahman Farole, Puntland’s president, following a spat with Mogadishu about whether Puntland’s education qualifications should be accepted at a national level. “Puntland educational certificates do not require Mogadishu’s stamp of approval. If anything, Puntland should approve Mogadishu’s educational certificates, because Puntland has a unified curriculum, functioning institutions, standardised examinations, and an educational policy,” the president explained, in a speech marking Puntland’s 15th anniversary of self-governance last August 1st.

Puntland, in other words, wants to be part of a federal Somalia, just as long as the federal government does not interfere too much. It may not officially aspire to independence, like Somaliland, but it demands almost complete autonomy from Mogadishu. And, thanks to Mogadishu’s weakness, it gets it.

Puntland’s position is not unique. Somalia’s current constitution, passed in August 2012, is based on federalism, which envisages strong regional and weak central government—a reaction both to the leadership vacuum in Somalia over the past two decades and Mr Barre’s brutal authoritarianism. But there is considerable disagreement both within the federal government and between the various regions (including Puntland and Somaliland) about the divisions of power within this federal system.

“What people want is not a separation…What they all want is confederation,” said Mr Aynte, referencing research performed by the Heritage Institute. “A very loose link to the central government in Mogadishu, and almost entire autonomy for everything else. Almost like a European Union-type confederation; they might not know the political science terms for these things but what they’re saying to us is they want very minimal relations with the central government…the federal government is not receptive to this idea. Some think the Mogadishu government is even resisting the idea of a federation, let alone a confederation; what they want is more of a centralised unitary state where the ultimate power rests with the central government but where regions are responsible for administration.”

Mogadishu’s position is not limited to holding onto its territory and expanding its powerbase, although those are both powerful factors. It is also mindful that allowing Somaliland and Puntland too much autonomy sets a precedent, which Somalia’s other regions could follow; and, dangerously, which neighbouring countries could take advantage of.

Jubaland, a region in south-central Somalia, is a prime example of these fears. Its main city, Kismayo, is Somalia’s second largest and a former stronghold of the Shabab. Sheikh Ahmed Madobe, leader of the infamous Ras Kamboni militia, which fought alongside Kenya during the 2011 invasion, now runs this approximate 87,000 square-kilometre territory, slightly larger than Austria.

An agreement with Somalia’s federal government signed in August in Addis Ababa, officially known as the Jubba Interim Administration, has legitimised Mr Madobe’s control. Some have hailed this agreement as a victory for Somalia’s neighbours because it put Kenya and Ethiopia in an excellent position to capitalise on Sheikh Madobe’s notoriously fickle loyalties. (His Ras Kamboni brigade was once an important strategic ally for the Shabab.)

Kenya, in particular, is known to be invested in the idea of Jubaland as a friendly buffer state, which will insulate it from Somalia’s instabilities. Nairobi is unlikely to pass up the opportunity to wield its influence there—even if it seriously undermines the Mogadishu government.

Somalia is often described as one of the world’s most homogenous nations, a place where almost everyone shares the same language, religion and ethnicity. This fact is often cited to underline the observation that homogeneity does not necessarily breed peace and stability; that humans, no matter how alike, can always find concerns that divide them and issues to fight over. The various semi-autonomous, fully autonomous and would-be independent regions, which the hapless Mogadishu government tries to rule, seem to prove this dictum.

Another lesson, however, can be drawn from Somalia’s balkanisation, one that is a little more encouraging. In the midst of all the fighting and the poverty, pockets of the country work, particularly Somaliland. In the world’s most failed state, there are areas that have succeeded. Perhaps Somalia, and the international community, should be encouraging these areas to share these governance lessons with the rest of the country, rather than force them to bow to the authority of a government in Mogadishu that has contributed so much to Somalia’s malaise.