Kenya relies on hydro-generated power for nearly 50% of its energy needs. Failed rains and the resultant catastrophic droughts have led to severe shortages in the East African nation’s daily electrical supply. To bridge this energy gap, an ambitious wind farm project is rising on the shores of Lake Turkana. Charles Kerich guides us through this massive venture, the largest of its kind in Africa. It is expected to provide 300MW of low-cost power to the national grid and lead the way in zero-emission power generation.

When Dutch national Willem Dolleman first started camping on the shores of Lake Turkana in the 1980s, he was immediately struck by the powerful wind. Although the Rift Valley’s drafts were useful for keeping the campfire burning, gale forces would occasionally uproot his tent and blow it away. Between cursing at having to re-pitch the tent and cooking the fish he had just caught, Dolleman began to have quixotic dreams of turning the wind into electricity.

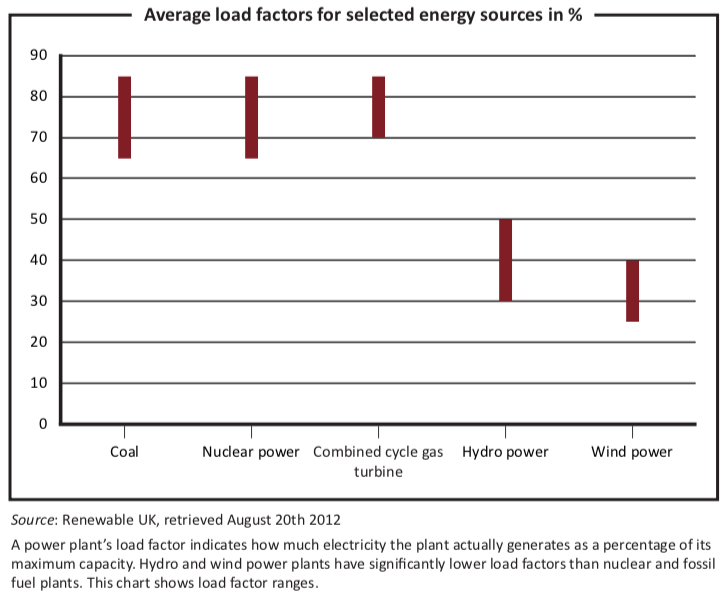

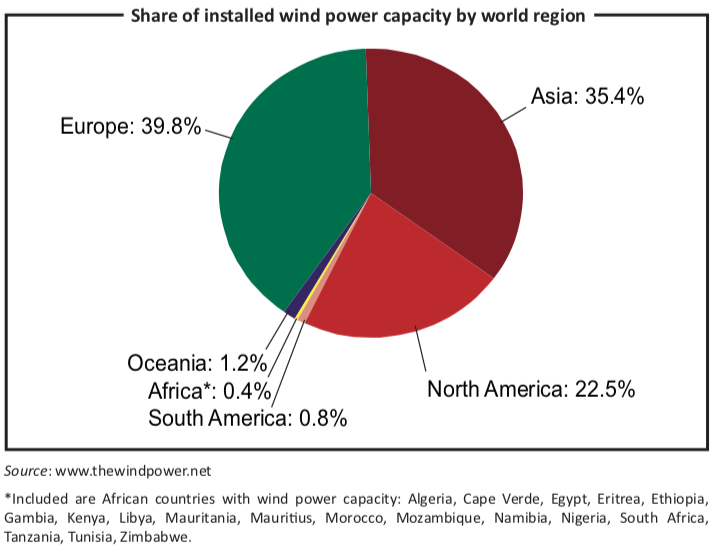

Though his native Netherlands had utilised wind energy for centuries, it was not the right time for a wind farm, especially in Africa. Oil prices were still low and no one was willing to cough up the money or marshal the resources to build windmills in the middle of nowhere. Still, Dolleman, a game ranch manager, persevered. He persuaded the German Wind Institute (DEWI) to measure the air currents and discovered that the winds in Turkana blow consistently at 11 meters per second on average.

“These results are among the best DEWI has ever encountered and can be compared to ‘proven reserves’ in the hydrocarbon industry,” according to a Global Energy Network Institute report.

Three decades later, the winds of change are blowing. Wind energy and other renewable energy sources are all the rage. The cost of oil has shot up. Repeated droughts have diminished the flow of rivers and curtailed the production of hydroelectricity. As a result, the world is looking for alternative sources of energy.

Power blackouts are only too familiar to Kenya’s 40m people. The exact loss of revenue from electricity outages is fuzzy, but a World Bank study indicates that the disruption of power costs Kenyan firms about 7% of their annual sales revenues. The unreliable electricity supply reduces Kenya’s annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth by about 1.5 percentage points, the study says. The country’s sole distributor of electricity, Kenya Power and Lighting Company (KPLC), has come to be known as Kenya Paraffin Lamps and Candles, the alternative sources of light every household keeps.

The company protests that it is not entirely to blame. An economic slumber in the 1980s and 1990s resulted in sparse investment in infrastructure and energy development specifically. Currently, peak demand for electricity stands at 1,200MW against a supply of 1,296MW.

The Kenya Electricity Generating Company (KenGen) is responsible for producing the electricity which KPLC then distributes. It has outlined strategies to increase power supply to 15,000MW by 2030, mainly by setting up a nuclear power plant, developing geothermal plants, promoting solar energy and increasing water power.

KenGen generates 47.8% of the nation’s power through hydroelectric dams, subjecting the country to rations and shortages during the dry seasons. This often leads to increased tariffs because emergency power must be purchased from independent power producers who use diesel.

The utility generates another 37% from fossil-based thermal plants, 12.4% through geothermal power and 2.4% through bagasse (the part of the cane left after the sugar is extracted) co-generation, which uses a heat engine or power station to generate electricity and heat. Wind accounts for 0.3% of Kenya’s energy.

Despite the massive wind project in Turkana, wind energy will command less than 10% by 2030.

The wind farm will hold 365 turbines, each 48 metres tall, on a site that stretches over 40,000 acres (162km2) in north-eastern Kenya. Projected to produce 300MW of power, the Turkana project is more ambitious than Africa’s current largest wind farm in Morocco with 165 turbines and a capacity of 140MW.

Construction of the massive wind farm project on the shores of Lake Turkana began last July with a road to the site, a major challenge. The nearest existing road is 250km away and in between lies a lunar landscape: rugged, rocky and remote country with few human settlements. Moving 28-tonne generators, three-tonne blades and hollow masts will require at least 12,000 round trips. A road had to be built first.

“We are in the middle of nowhere and there is no infrastructure in place,” said Carlo Van Wageningen, the project chairman. “The wind farm site resembles photos of the surface of the moon.”

The African Development Bank (AfDB) agreed to fund the road. Finding the financing for the $720m project was another hurdle. The project is broken into six components: the road; the power plant; the substation; the transmission line; a village to house staff; and the large capacitors to stabilise the power and feed it into the national grid.

Once the AfDB agreed to fund the road, the Spanish government committed $175m for the 428km transmission line.

The AfDB further undertook to mobilise funding for 70% of the $720m on condition that the Lake Turkana Wind Project (LTWP) came up with 30% as equity. The AfDB will put up $124m of its own, while co-arrangers Standard Bank and Nedbank will add another $124m. Investment funds and other co-developers will finance the rest.

In May 2012, the project looked shaky after international financiers demanded additional guarantees before signing on. The financiers wanted to know what would happen if the wind farm started to generate electricity, but the transmission line from the wind farm to the national power grid was incomplete. They also wanted guarantees in case the power lines were vandalised or destroyed by an act of God.

To make matters worse, the construction of the transmission line is scheduled to take 23 months while that of the wind power plant requires 26 months. If both commence at the same time, Kenya Power would have a buffer period of three months to start taking the power before the wind company would start sending bills. The investors demanded to be fully indemnified from the losses that would follow if a delay prevented electricity uptake. Government officials began hinting that this period is too tight and sought to renegotiate.

Another concern was whether Kenya Power could take up all the power produced and make regular payments. With the spanner in the works, the wind project looked set for a long delay as lawyers made protracted boardroom arguments.

Kenya Power turned to the Kenyan government, which in turn asked the World Bank for help to address the concerns about delays. The Multilateral Guarantee Investment Agency (MIGA), an agency of the World Bank, agreed to provide investment guarantees as insurance cover for lenders and possibly shareholders. Among other specified issues, the guarantee covers political risks, including a change of government that could result in different policies such as a change in the power tariffs. The agreement calls for KPLC to pay $0.12 per kWh, about 60% cheaper than Kenya’s thermal power plants, according to LTWP documents.

The project has been registered with the United Nations, a prerequisite to be eligible to claim or trade in carbon credits. From its greenhouse gas emission reductions it expects to earn about 1m carbon credits, about $8.6m a year at current carbon prices.

Even if the wind farm were to become a phenomenal success, Kenya still needs to invest heavily in electricity generation. Most of its electricity illuminates only cities and trade centres, while the majority of villages in rural areas remain in the dark.