Somalia: the Shabab

Is stability returning to Somalia when the Islamist militant group still controls most of its territory?

Bad guys do not get much worse than the Shabab. The Islamist militant group runs much of Somalia like its own personal fiefdom and was most recently in the headlines for conducting the horrific attack on Westgate Mall in Nairobi. Along with Boko Haram and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, they are among the most dangerous and feared political groupings in Africa, responsible for vicious acts of terrorism and numerous instances of brutality towards their own people. A potent cocktail of nationalism and fundamentalist Islam drives their actions. Their leaders have publicly pledged fealty to al-Qaeda.

Although the Shabab are in the crosshairs of the war on terror, they remain an oft-misunderstood organisation, whose track record in Somalia is far more nuanced than their bogeyman image leads most outside observers to assume.

To understand the Shabab’s politics, it is necessary to understand where they came from. In 2006, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), a relatively moderate coalition of Islamist groups, led Somalia and for the first time in decades provided something approaching stability. Through the imposition of sharialaw, and ties that transcended traditional clan-based allegiances, the ICU brought a welcome measure of peace and development to Somalia.

This stability was short-lived. Weary of the Islamist threat on its border, and cheered on by an American administration that struggles to separate political Islam from terrorism, no matter what its form, Ethiopian troops crossed the border and quickly unseated the Somali government, replacing it with a secular civil administration composed mostly of exiles from Nairobi, called the Transitional Federal Government or TFG. The ICU, in disarray, fractured into two broad movements: the moderates, who put their lot in with the TFG; and the hardliners, bitterly critical of foreign intervention and their one-time colleagues who sold out to it. These hardliners form the core of Harakat al-Shabab al-Mujahideen – the Movement of Striving Youth, [not Jihadist Youth?]usually known as the Shabab, or “the Youth”.

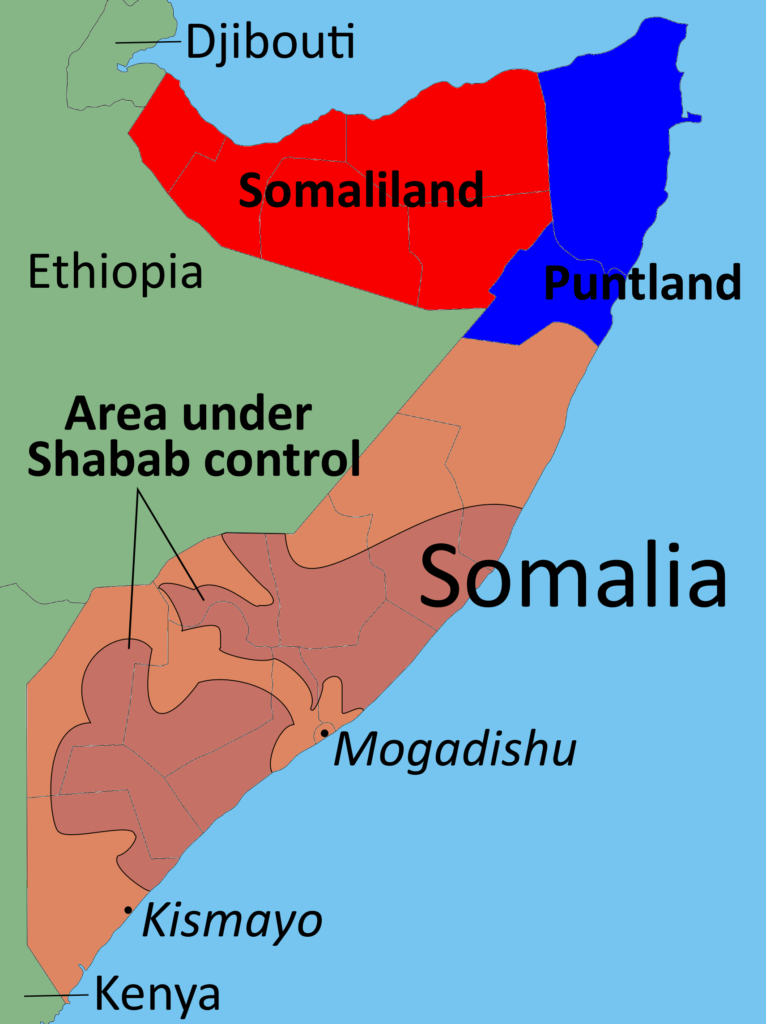

Better organised than the TFG, and with the Ethiopian invasion as a potent recruiting tool, the Shabab went from strength to strength and soon controlled most of Somalia, with a few major exceptions: the would-be independent state of Somaliland in the north-west, the autonomous region of Puntland in the north-east, and a tiny slice of the capital Mogadishu, where the TFG was propped up with the help first of Ethiopian troops, and then the African Union Mission in Somalia (Amisom).

Although not recognised internationally, the Shabab was Somalia’s de facto government. It wasted no time in imposing its hardline version of Islamic law on the territory under its control. Its regime was so harsh that even Osama bin Laden was critical. In letters discovered in bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound after his death, bin Laden expressed his concerns with the Shabab’s rigid implementation of Islamic law and excessive use of force, according to news reports.

Justice was summary, and punishments incredibly severe: floggings, amputations and beheadings became commonplace. Young men and boys were forcibly recruited into military units. Pastimes like listening to music and watching sport were discouraged, part of a range of draconian social restrictions designed to eliminate any Western influences. Western clothing was also forbidden, as was long hair for men.

Women had it particularly bad. “Many local Shabab authorities devote extraordinary energy to policing the personal lives of women and preventing any mingling of the sexes,” said Human Rights Watch in a 2010 report, detailing instances of women being punished for wearing the wrong kind of abaya, the Muslim full-length garment for women, or pursuing commercial opportunities which brought them into contact with men, such as selling tea.

At the same time, the Shabab continued to wage their war against the transitional government, and later Amisom. This rarely took the form of direct confrontation, but instead the Shabab adopted typical guerrilla tactics, including targeted assassinations, suicide bombings and ambushes.

The situation changed dramatically in October 2011, when Kenya—determined to stamp out the instability in Somalia, which was hurting its crucial tourism and shipping industries—launched a sudden invasion to unseat the Shabab. Although the invasion had no international legitimacy at the time, a month later the African Union (AU) and the United Nations in February 2012 approved the military incursion and Amisom absorbed the Kenyan troops. Although Kenya’s progress was slow, it was relentless. It succeeded eventually in pushing the Shabab out of many of its strongholds, including Mogadishu and the group’s economic centre Kismayo, from where it had exported charcoal, which funded much of the Shabab’s operations.

This was a huge blow to the Shabab’s authority, but it was not fatal. The loss of Kismayo has not proved to be a financial disaster, with the group continuing to generate between $70m and $100m a year, according to the UN. In addition to the sanctions-busting charcoal exports, which have been routed through other ports, the Shabab has an efficient tax system that imposes duties on ports, goods and services, domestic produce and even personal income. It also raises funds through enforced “jihad contributions”, bribes at checkpoints and by rerouting funds from overseas designated for Islamic charities.

Though it has been kicked out of most urban centres, it still controls vast swathes of Somalia. At present, the Shabab “remains in control of most of southern and central Somalia,” concluded the UN Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea in its July 2013 report. Given that northern Somalia (Puntland and Somaliland) operate autonomously, this means that the Shabab continue to control more territory than the federal government. (The federal government replaced the Transitional Federal Government in August 2012.) Diplomats and commentators, eager to portray Somalia as having turned some kind of corner, often overlook this fact.

Even more impressively, the monitoring group estimates that the Shabab are able to maintain this control with a military strength of approximately 5,000 fighters, which has remained “arguably intact in terms of operational readiness, chain of command, discipline and communication capabilities” despite the Amisom/Kenyan offensive and the loss of crucial revenue sources such as the Kismayo port. There is some debate over this figure – in a recent feature, The Guardianreferenced an unnamed Kenyan military intelligence officer who puts the true figure at three times higher, and growing – but either way the Shabab’s fighters are outnumbered by their opponents.

There are 17,765 Amisom troops stationed in Somalia, a number which is set to rise to 24,000 following a decision by the African Union (AU) to reinforce the mission (provided extra funding can be raised from the UN Security Council and international partners). This would double the 18,000 military and 6,000 police troops available to the federal government.

This clear numerical disparity gives rise to an intriguing paradox: how are the Shabab able to maintain so much territory with so few troops?

The UN report offers a clue: “Multiple factors explain the resilience of the Shabab, including longstanding support from some major clans, the capacity to provide a stable environment for business, livestock farming and agricultural production and the ability to represent for local elders a credible alternative to regional warlordism or to Mogadishu-based institutions, still perceived as a source of instability, violence and corruption.”

To be blunt, for all its brutality, the Shabab – with its functioning justice system, tax regime and relatively low corruption levels—offers better governance than the federal government. Like the ICU before them, territory under the Shabab’s control is characterised by stability and the rule of law. Even if that law is particularly harsh, it is often considered preferable to the uncertainty and corruption of other power brokers in the country.

“The Shabab are, let’s face it, far better administrators, however brutal, than the government. The areas under their control are very stable. An extreme form of justice system works, and people feel safe and secure,” observed Abdi Aynte, director of the Heritage Institute in Mogadishu, Somalia’s first independent think-tank. “Sometimes people feel offended when we say these kinds of things. But that’s the reality. Remember we have our own extended families and clan members who are still living in Shabab-controlled areas. They really feel safe for their property, their farms, their cars, whatever they have.”

Two other factors add to their popular appeal. First, the Shabab is able to use foreign intervention in Somalia—particularly the legally dubious Kenyan and Ethiopian occupations—to mobilise support and recruit new members, portraying themselves as the only credible opposition to foreign occupation. Given the extent to which foreign countries prop up the federal government, both financially and militarily, there is some merit to this argument. Second, the group has succeeded where others have failed in bridging clan and sectarian divides, mainly thanks to its strict Islamist ideology.

Militarily, the Shabab’s smaller numbers are not necessarily a disadvantage. The world’s recent history is littered with examples of asymmetric warfare where more troops and resources do not guarantee victory. Think of the US in Afghanistan, or the Syrian military’s inability to contain rebel groups.

“The strength of [the Shabab] need not be seen in the sense of their actual strength on paper or conventional assessment,” said Andrews Atta-Asamoah, a researcher who specialises on the Horn of Africa at the Institute for Security Studies. “For a group that has adopted guerrilla warfare, 5,000 is more than enough to make the country ungovernable and insecure. Westgate has proven that with few gunmen, they can achieve more havoc. Their strength should thus be seen in relation to the vulnerabilities and weaknesses of Somalia and the countries in the region.”

Of course, the Shabab have not emerged completely unscathed from their territorial setbacks. Amisom’s inexorable advances have exerted pressure on the Shabab’s leadership, bringing into the open in dramatic fashion the divisions between the Shabab’s top officers. At stake was the Shabab’s direction: specifically, whether it should stay true to its nationalist roots or embrace the global jihadist ideology favoured by its leader, Ahmed Abdi Godane.

In typically ruthless fashion, Mr Godane got his way, consolidating his own power in the process. In the process, several key figures including his deputy, Ibrahim al-Afghani, were killed and several others were forced into hiding. Of particular concern, as far as Mr Godane is concerned, is influential cleric Sheik Hassan Dahir, better known as Aweys, who gave himself up to the authorities in Mogadishu in June.Sheik Aweys is now in prison in Mogadishu, with authorities yet to determine what to do with him. It is still unclear whether he has spilled valuable secrets to the federal government or whether his apparent defection may undermine Mr Godane’s position.

In this context, the Westgate attack in Nairobi—for which the Shabab claimed credit—is as much a reflection of the Shabab’s internal struggles as it is a punitive response to Kenya’s military actions in Somalia. Mr Godane, in authorising such a spectacular show of force in a foreign country, was not just making good on his promises to wreak revenge on Kenya. He was also proving, both to his own followers and to the broader global jihadist movement, that his group is willing and able to undertake these types of actions; that, with the nationalist faction sidelined, the Shabab’s ambitions extend beyond Somalia’s borders.

Thus it is a mistake to view the Shabab only through the prism of terrorism or global jihad. It may have formalised its alliance with Al Qaeda in February 2012, but this relationship is still more symbolic than operational. Whatever Mr Godane’s intentions, the group remains most influential within Somalia’s borders, where it displays a commitment to governance that has been lacking in Mogadishu at times. If it is willing to listen, there are lessons that Somalia’s new government can learn from the Shabab’s success. Only by offering stability, rule of law, accountability and inclusive economic growth will the federal government be able to neutralise the Shabab’s threat.