The quality of governance is dynamic, not static. In short, it shifts, sometimes quickly and, at other times, more slowly. It is precisely this attribute of governance that makes it suitable for empirical measurement. Governance is also central to every facet of human life, with its downstream effects impacting society, the environment, the economy, and human security.

With these two assertions in mind, there is perhaps no more appropriate locus for empirically measuring governance than the African continent. The continent is striving to economically develop at a time when technological innovation and data-driven decision-making are more ubiquitous than ever.

The empirical measurement of governance can therefore play a crucial role in helping identify areas of governance progress and areas of shortfall within the African setting. We can also use the insights derived from measures of governance quality to understand the drivers of key phenomena such as development and conflict. In turn, this can aid in the development of evidence-based policymaking models.

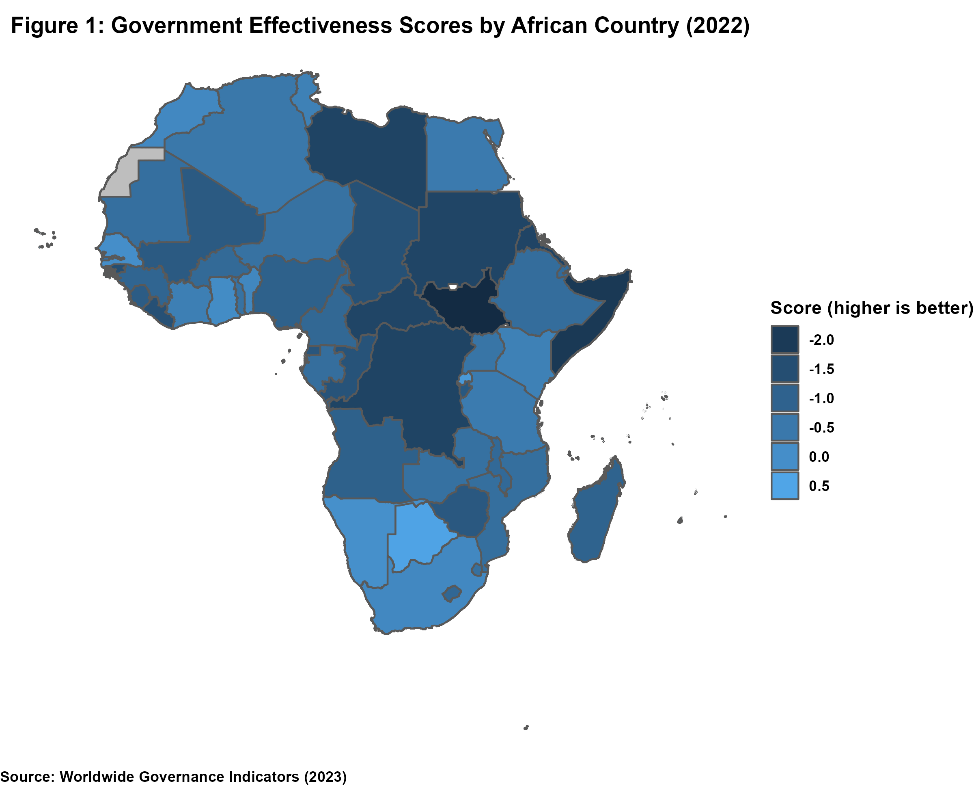

To an extent, broader society has recognised the potential for providing an independent but empirically sophisticated measurement of national-level governance. Annually, for instance, the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) project publishes governance scores for all countries on six dimensions of governance: control of corruption; government effectiveness; political stability and absence of violence or terrorism; regulatory quality; rule of law; and voice and accountability. Figure 1 maps the scores for each African country on the WGI indicator of government effectiveness for the most recent available year (2022).

Within the African setting, the Mo Ibrahim Foundation produces a robust national-level governance measurement instrument called the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG), which annually scores and ranks all African countries on overall governance, as well as on the components of foundations for economic opportunity, human development, participation, rights and inclusion, and security and rule of law.

One area where governance measurement in Africa has been less pronounced is at the local level. Naturally, this is of concern because the local level is the level of government closest to the ordinary citizen. Moreover, in many African countries, it is local government that is responsible for the provision of core basic services, including drinking water, adequate sanitation, and waste removal.

Local government, then, is the level of government through which many African citizens form their perceptions of the state, while also being a key structure that will determine Africa’s ability to combat some of the core governance and welfare challenges the continent faces. Among these are high child mortality rates, environmental degradation, corruption, and localised political instability.

However, if we only have national-level measures of governance performance, then we have little clarity about how the state of governance differs within nations, an equally important consideration. Ultimately, the ability to measure localised governance in Africa will give us a more realistic understanding of how we can effectively resolve these threats and by when.

Some African governments in relatively well-capacitated states have recognised this and have introduced assessments designed to empirically measure the state of governance and development at the local level. Examples of such assessments are the South African government’s ‘State of Local Government’ report and the Ghanaian government’s ‘District League Table’, for which they partner with the United Nations Children’s Fund, and which focuses on providing a local-level assessment of the state of children’s welfare.

These are welcome and essential initiatives, though with two caveats. First, unlike the governance measurement tools produced by the World Bank and the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, they are government-developed assessments and, by definition, not independent. Second, because they are government-led initiatives, they have no scope for growth beyond the borders of their nations.

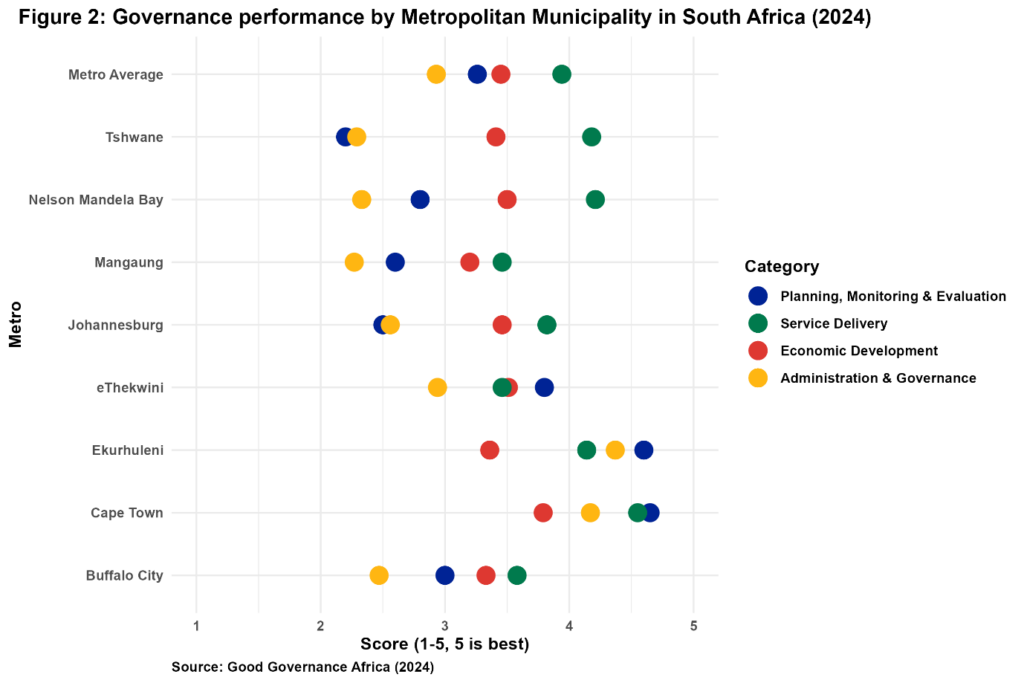

One governance assessment tool that independently measures the state of local governance and aspires to expand across the continent is Good Governance Africa’s (GGA) Government Performance Index (GPI). Since its inception in 2014, the GPI has focused on providing an assessment of local governance across South Africa’s 257 municipalities. The intent, however, is to expand the GPI, starting with other southern African countries such as Botswana, Namibia, and Zambia soon. In the long run, expanding the GPI to other parts of the continent is a major aspiration of GGA.

Figure 2 provides a brief glimpse of the value of a tool like the GPI for policymakers, civic organisations, international organisations and the private sector. Specifically, the graph visualises governance performance in four key categories across South Africa’s eight metropolitan municipalities. Combined, nearly four in 10 South Africans reside in these areas, highlighting their importance. It is clear from the graphic that the aspect of governance that major South African cities struggle with most is administration and governance, which encompasses aspects of accountability, compliance, financial soundness, and human resources management.

South Africa will soon not be unique among African countries in having such a high concentration of its population residing in a handful of cities. In fact, estimates produced by the African Development Bank suggest that by 2030, approximately half of the continent will be living in urban areas. An expanded GPI would be able to offer highly specific insights into the state of sub-national governance across Africa, along with the associated benefits of encouraging responsible commerce within well-governed areas, while also providing independent guidance on the sort of interventions which less well governed areas need most.

While urbanisation is one of the African continent’s most pivotal trends, it is equally vital that we develop an empirical understanding of local governance in rural areas where most of the continent still lives. It is here, however, where Africa’s core challenges around a lack of data collection capacity and technical capacity are most felt.

An accurate assessment of local governance in rural areas is possible in a country like South Africa, which has effective financial administration and data collection institutions. Both GGA’s GPI, and the government-led ‘State of Local Governance’ report, draw on regularly updated and reliable data produced by credible institutions like Statistics South Africa, the Auditor-General of South Africa, and the National Treasury.

Such capacity is lacking in most African countries, a problem that becomes more obvious the more one travels away from urban centres. Therefore, a tool such as the expanded GPI should also aspire to be part of a broader effort to improve the statistical and technical capacities of these types of institutions.

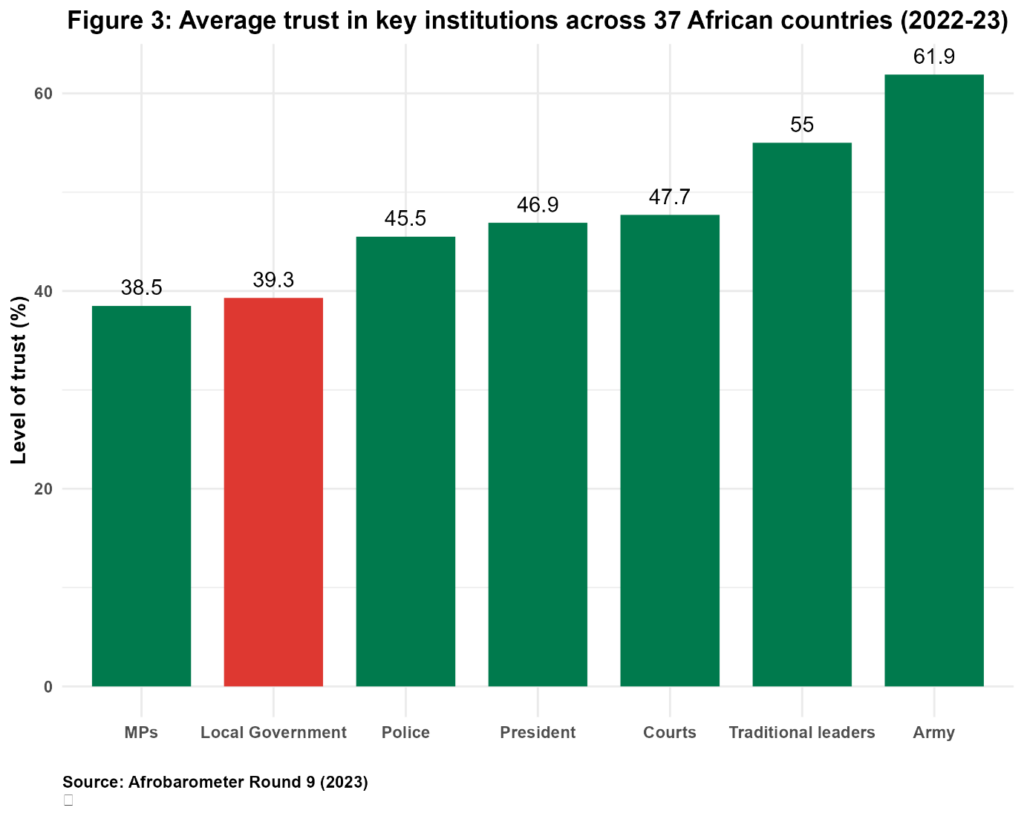

As Figure 3 suggests, the necessity of getting a more accurate picture of the state of local governance extends beyond the realms of academia and analysis. According to Round Nine of the Afrobarometer survey, local government was the second-least trusted institution among key institutions, with only 39.3% of respondents across 37 countries saying they trusted their local government councillor either “somewhat” or “a lot”.

This reflects a crisis in both the standard of local governance in many African countries and the public legitimacy of many local government structures across the continent.

Developing reliable, accurate and independent empirical tools designed to understand the state of local governance across Africa can help to improve the standard of that governance, especially if it results in more informed policy decisions. If it succeeds in this mission, then it can also play a crucial role in making citizens feel more connected to local politicians, officials and institutions that are meant to serve the public interest.

Pranish is a Senior Data Analyst within the Governance Insights & Analytics programme. He holds a Master of Arts in-Science obtained with distinction from the University of the Witwatersrand. This degree formed part of the Department of Science and Innovation's National e-Science Postgraduate Teaching and Training Platform. His research interests include comparative politics, local governance, quantitative social analysis and political geography.