Democratic Republic of Congo: post-conflict elections

by Stephanie Wolters

Do-gooding outsiders can make or break elections in countries emerging from war. These nations are usually broke and have a difficult time organising and paying for polls. The United Nations (UN) often steps in to help.

In 2006, after 32 years of kleptocratic rule by Mobutu Sese Seko and years of civil war which left several million dead, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) held its first multiparty elections in nearly 40 years. The UN rallied huge amounts of funding and organisational support and the elections were considered a success.

Five years later, in 2011, the DRC again held presidential and parliamentary elections. This time, intimidation, arbitrary arrests and allegations of fraud marred the elections. Why the difference? Financing, organisational support and advice from the international community had dropped sharply.

The mood in the DRC before and after the 2006 polls was one of triumph; the elections were a culmination of years of hard work.

The various parties had taken the first step towards the 2006 election in December 2002, when they signed the peace accords to end the war, which had started in 1998. A three-year transition period followed. During this second step, the transition government elaborated the institutional and governance architecture for the future.

Neither of these two periods was easy. Warring parties were at odds and frontlines remained in place throughout the peace talks. Even after the ink on the agreement had dried, rebel factions cited security concerns; months went by before they agreed to travel to Kinshasa, and then only with large military contingents in tow.

A difficult period of building consensus around new institutions followed. Agreement had to be reached on the architecture for the country’s first multiparty election and the provincial assemblies. A new constitution would pave the way for increased decentralisation. There were countless delays and endless spats between the many players in the transition government and what was to be a two-year transition turned into three.

The international community’s massive support and funding, as well as strong deterrents against overturning the transition process, are responsible for the successful process that culminated in the 2006 presidential and legislative elections. One of the UN’s largest and most expensive peacekeeping missions, better known by its French acronym MONUC (now MONUSCO), played a key role by providing an ongoing stabilising presence. In addition, numerous envoys as well as the International Committee to Support the Transition (CIAT), a body composed of the ambassadors of 12 countries, helped and advised the transition government. All worked tirelessly to keep the different factions in line and the process on track.

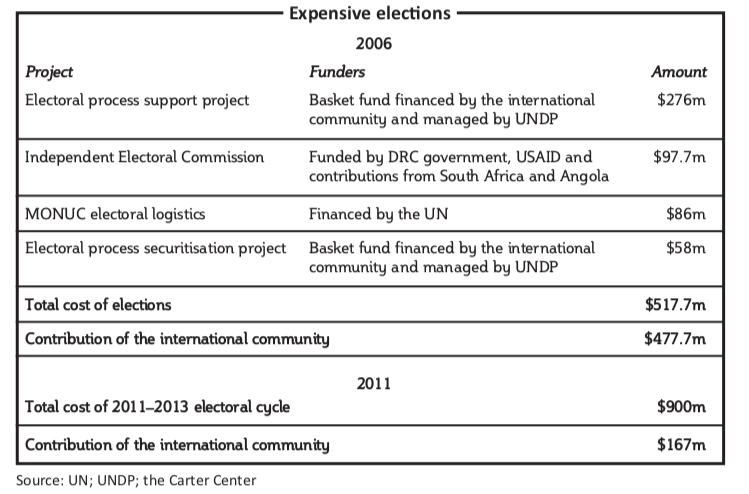

Money also helped. The UN and the European Union (EU), in particular, financed the elections, which ultimately cost over $500m. Equally important, MONUC gave huge support to the National Electoral Commission (CEI), which was responsible for the bulk of the electoral operations, from procurement to logistics and monitoring.

The international community would have condemned Congolese parties that acted as spoilers or derailed the transition and election process, while the Congolese electorate would have shown their displeasure with such behaviour at the polls. This acted as a disincentive for any parties to disrupt the process.

The electorate expressed intense confidence in the electoral process mostly because outsiders were managing the process. Many registered to vote and they turned out in large numbers on election day. For a brief moment, the Congolese seemed to trust their political system, to feel that their vote really counted. Joseph Kabila won the 2006 presidential elections following a second-round run-off with his main rival, Jean-Pierre Bemba.

Unfortunately, the elections held in the DRC in late 2011 presented a very different picture, playing out like many other post-conflict polls. The main difference between these and the earlier elections was the level of support — financial, material, organisational and advisory — from the international community. This time around, the Congolese government was responsible for organising everything from voter registration to the polls themselves.

Long before the elections took place, developments in the political environment did not bode well for their transparency. First, the national assembly, dominated by Kabila’s party, voted to scrap a second round run-off if no candidate won an absolute majority in the first round, a move widely interpreted as facilitating Kabila’s victory against a divided opposition. Then Kabila appointed a close associate, Daniel Ngoy Mulunda, to head the Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI), thereby depriving the body of independence and credibility.

This had a negative effect on relations with the international community, said Denis Kadima, the head of the Electoral Institute for Sustainability in Africa (EISA), in an interview with Africa in Fact. Though it remained an adviser to the electoral process, the financial and other support it provided was only a fraction of that given in 2006.

“The first time around, the country had not had elections in 40 years, they were very much listening (to the international community),” he said. “Then came the next election, you can look at how the next commission was put in place, and who was chosen to head that commission. Relations between that commission and the UN were terribly tense. There was no engagement, it was like ‘we know it all’.”

A severe decline in international assistance to the electoral process can also lead to a drop in standards and transparency. In the DRC in 2011, international funders donated about $167m, according to the Carter Center, a US-based human rights group, while the total cost of the 2011 elections, according to Congolese scholar Mvemba Dizolele, came close to $900m. In some cases, Kadima said, the international community may be willing to continue to provide some support. The new government, however, may want it to be less involved than in the first election.

“By the second election, times have changed. But the reality is that the winner will try to entrench their power. That is why second elections tend to fail, the quality is always poorer because, first of all that, first electoral commission is transitional, all the knowledge they have accumulated in the course of that transition, it’s gone, because there is a new commission to mark the end of the transition. Government also wants to assert itself: ‘I have been elected, you can’t come and tell me what to do, the people gave me the mandate’,” Kadima explained.

High levels of cooperation during the transition period are exceptional, while the international community’s mandate in second elections is usually much more limited, he added. “International organisations understand that it is difficult to sustain the same level of professionalism and efficiency from the transitional election to the post-transition election,” Kadima said. “People would be willing to go in to help, but the framework, the mandate, the involvement, the roles are different. They (the international community) have their hands tied…There should be some mechanism to ensure that the winner does not take away all the positive things that were established during the transition. How do you do that when you don’t have that mandate?”

Serious irregularities such as intimidation of voters and election monitors and opaque counting procedures, tarnished the DRC‘s second election. Local and international election observers called the process flawed, but stopped short of declaring the results illegitimate. The domestic opposition rejected the results. Some parties chose to boycott the national assembly, including the Union for Democracy and Social Progress, the country’s main opposition party, which won more seats than any other opposition party.

“The element of leadership is key. Whoever is elected, if they don’t take responsibility for the future of their country, if they don’t show leadership, if they are short-sighted, want to see things for their own benefit and for those around them, it will be a vicious circle,” Kadima said.

Meanwhile, the schedule for provincial elections, which were due to be held in 2012, and local elections, which have never been held and are now effectively nine years behind schedule, have been suspended. The government says that it does not have the money to fund them, while donors have made international funds contingent upon a wholesale reform of the electoral commission. Although parliament voted last year to restructure the CENI, and a law to this effect was passed in May 2013, the reform has been controversial. The ruling party will continue to have the greatest number of representatives on the CENI and there is concern that it will try and maintain control of the institution.

The mood now contrasts starkly with the one of triumph after the 2006 polls. Most Congolese are disillusioned with the political system, while the Kabila government has been significantly weakened by the controversy around the election.