In recent years, the West African country of Togo has committed itself to the path of decentralisation, which led in 2020 to the first local elections in more than 30 years. However, over the past five years since the creation of 117 municipalities managed by majors, results have varied, with more work left to be done to meet the citizen’s expectations.

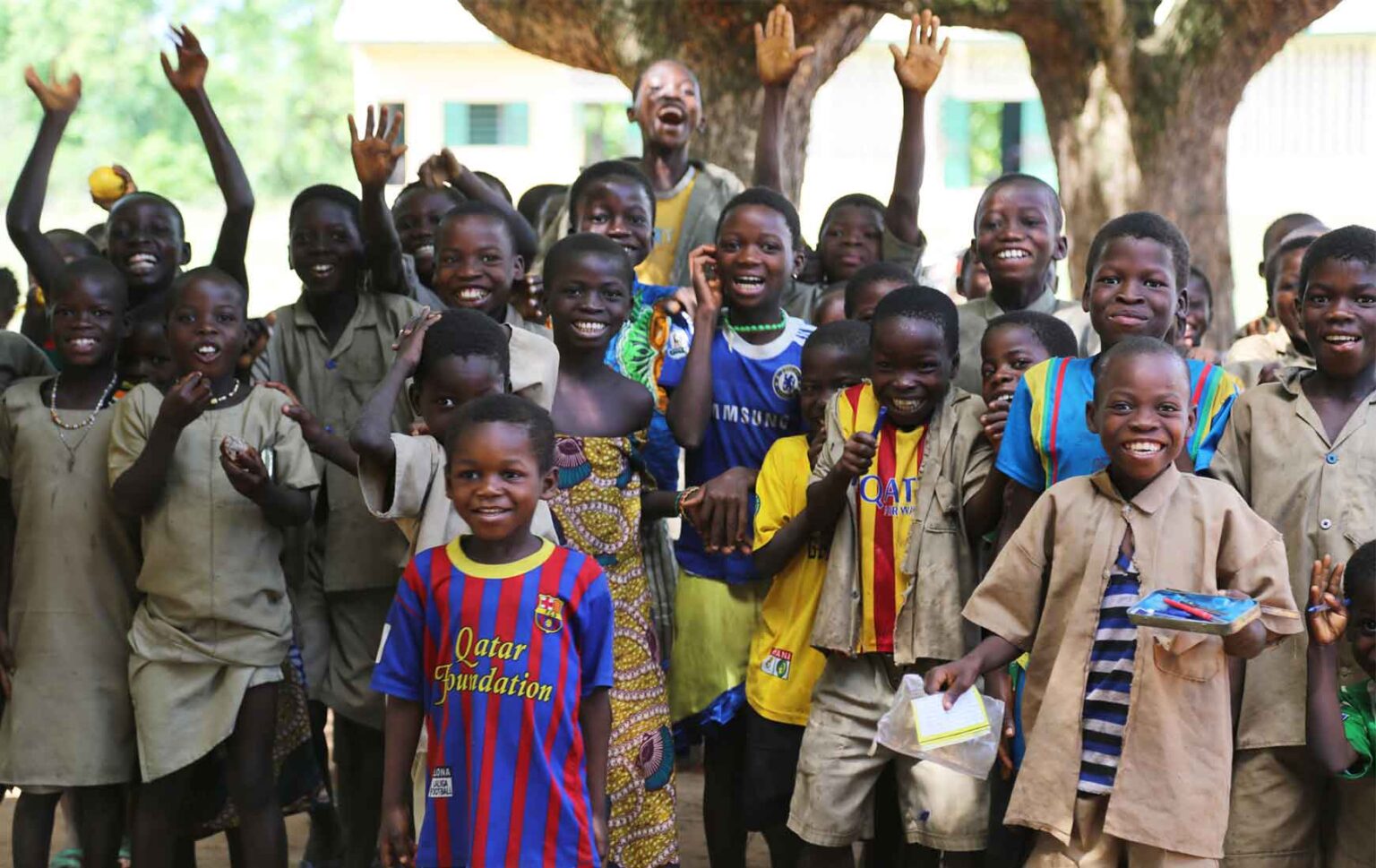

Policymakers and civil society organisations believe decentralisation will accelerate Togo’s progress towards achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals 2030. Indeed, analysts have tracked notable progress in education, health, sanitation, and access to drinking water, largely through the construction and renovation of infrastructure in all 117 municipalities. According to a report by a group of civil society organisations, ‘On achieving the Millennium Development Goals’ published in 2022, after a national survey carried out across all 117 municipalities, Togo has made significant progress in respect of five SDGs, including education.

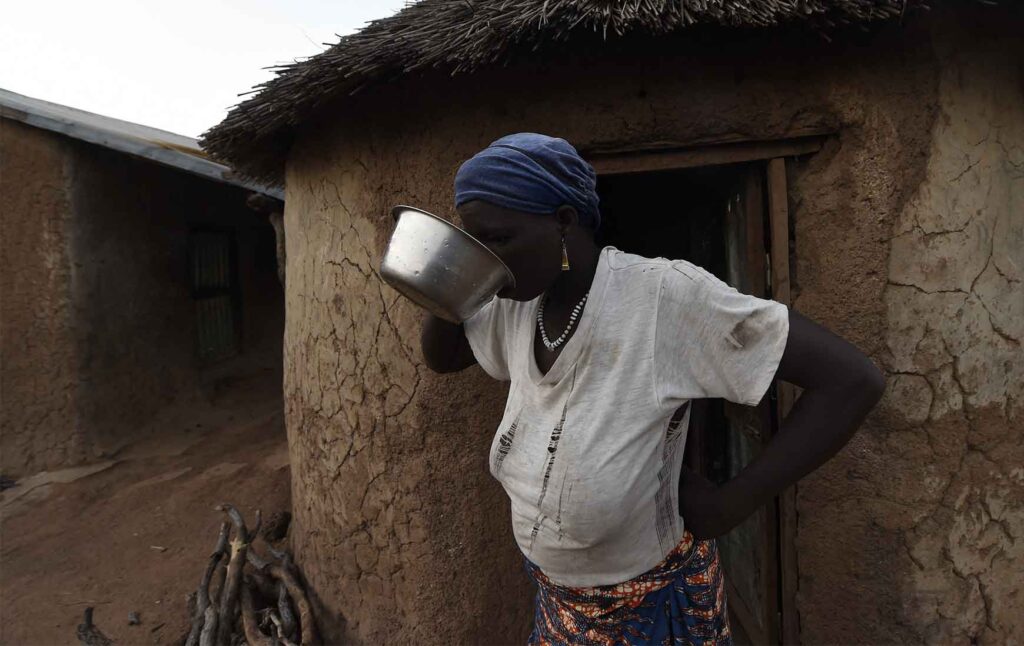

But despite detailed planning, some local administrations have pointed to lack of funding as a major impediment to achieving all 17 SDGs. “Despite our goodwill, we are unable to meet all the expectations of the people in our municipality,” Edoh Komi, the deputy mayor of the Golfe2 commune in the capital, Lomé, told Africa in Fact. “This is because we face a glaring lack of funding. The small allocation from the state is not enough to support our vision of achieving all the sustainable development goals in our municipality. Today, we are forced to target only certain priority goals, while we would have liked to invest in almost all sectors.”

This lack of funding for local administrations leaves some decentralisation experts sceptical that effecting municipal development plans before the end of their mandate in 2025 is achievable, creating a knock-on effect on achieving the SDGs by 2030.

“At this rate, saying that we will be able to achieve the Millennium Development Goals by 2030 is an unrealisable dream,” Ouro Bossi Tchakondo, a noted decentralisation expert, told Africa in Fact. “The [government] must review its decentralisation policy to allow local administrations to be much more financially autonomous, to create wealth that can be used to finance the development of their local communities.”

To accelerate progress, the government has, since 2021, adopted a shared responsibility approach. This requires national government to contribute to the efforts of local administrations through co-financing and shared management in the priority sectors of education, health, and sanitation. Thanks to this approach, municipalities can now finance their projects in these key sectors.

“There are 36 neighbourhoods in our commune, Golfe1, and one of the needs remains electrification,” explains Francis Pédro, a municipal councillor responsible for procurement in the commune. “We have developed a project to electrify 12 neighbourhoods per year to reach all neighbourhoods in three years. This project has dragged on due to a lack of funding, but we aim to achieve SDG 7 (affordable energy access) in our municipality.” He also pointed out that his municipality had succeeded in building new health and education infrastructure last year thanks to locally mobilised funding.

Local administrations do benefit from a special allocation from the state thanks to a support fund for local and territorial authorities set up in 2019. Allocations are determined according to a certain number of criteria, which include the poverty index, the surface area, and the number of inhabitants in a municipality. The country’s 117 municipalities have received approximately $24.5 million over three years.

Municipalities are also allowed to mobilise their own resources by implementing taxes and fees at a local level. This revenue increased from approximately $23 million in 2020 to $26.5 million in 2021. Local administrations are increasing initiatives aimed at mobilising additional resources to provide for the basic needs of their populations.

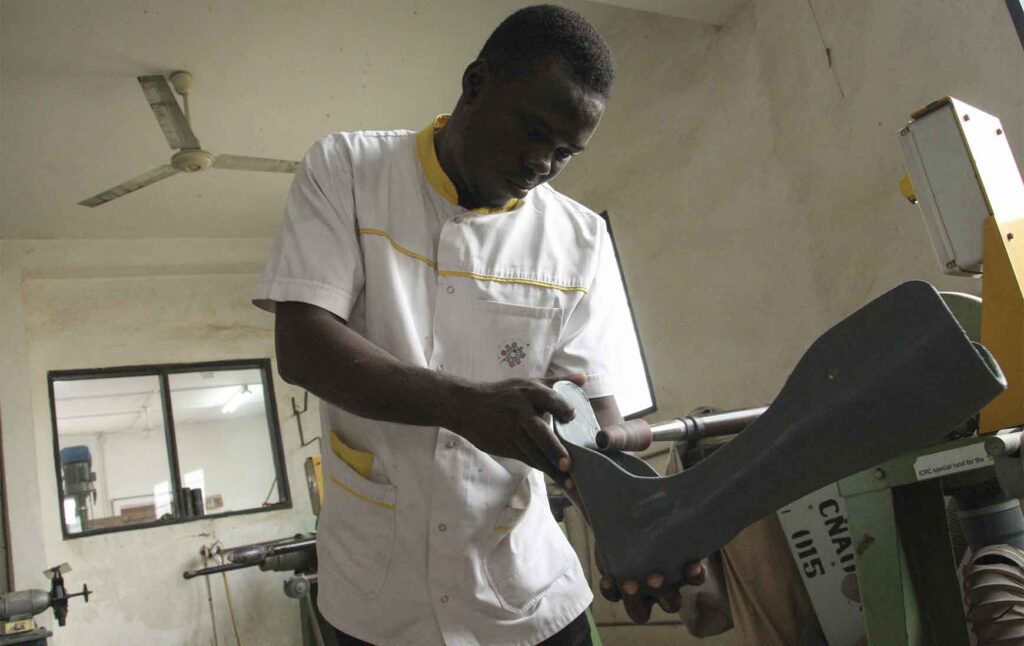

Germany, through the German Development Bank, has also stepped in. In November last year, the bank granted a financial package of more than 20 million euros to 69 municipalities. This will help finance social and economic infrastructure (schools, markets, health centres), the development of project management capacity (procurement techniques) and strengthen the capacities of other staff.

To properly channel resources and ensure efficient management, the authorities have implemented controls. The first was a commission to study and assess the budgets of local authorities, made up of delegates from all 117 municipalities, as well as officials from the Ministry of the Economy and Finance.

In addition to the commission, any disbursement of funds for a project proposed for financing by a local administration must go through a monitoring mechanism at all levels. However, this sometimes delays project financing, giving rise to complaints that central government is attempting to maintain control and interfere in projects initiated by local administrations close to the opposition.

“These mechanisms are not [necessarily] a bad thing since they are aimed at healthy and transparent management of resources,” Edoh Komi told Africa in Fact. “But it must be said that sometimes this process drags out local administration projects while citizen expectations are numerous and urgent on the ground.

“Originally, these different control mechanisms were not supposed to be a brake on municipal development, but at this rate, we have the impression that they are since many projects drag on before being given the go-ahead or rejected. In Africa, you know, everything that politicians do is for political aims or considerations. So, if opposition mayors do not manage to implement their development projects by the end of their mandates because of these control mechanisms, the population will say that [the mayors] did not keep their promises. As a result, voters will vote for no confidence in the next local elections.”

One solution suggested by local government experts is that civil society is given the role of monitoring development project implementation, producing regular reports in a participatory, transparent, and inclusive manner and reviewing progress to hold all stakeholders, including local administrations, to account for progress or lack thereof.

Bossi Tchakondo told Africa in Fact that the authorities needed to review the decentralisation process to involve citizen action. This would ensure grassroots populations could play their part in monitoring and controlling initiatives aimed at achieving the SDGs. But right now, Togo is trying to combine local governance with achieving the SDGs while also focusing on promoting the transparency and accountability of local administrations.

Blame Ekoué is the Togo correspondent for the BBC and for Paris-based media house, ANA. He has also reported for Associated Press and Radio France International. He holds a BA in Communications from the Leader Institute in Lomé. Formerly deputy editor of the West Africa Revue, he has been a contributor to the Lome-based Business and Finance magazine since 2015.