Kenya: using technology to fight tribalism

by Clar Ni Chonghaile

The bloodshed that followed Kenya’s last presidential election in 2007 shocked the world. As the pivotal polls on March 4th approach, people are nervously watching for signs of a repeat. In one of the continent’s most connected nations, that scrutiny has spread to cyberspace as people seek out the kind of hate speech that fanned the violence last time.

A special government task force, tech whizz kids and media officials are involved in a series of initiatives to monitor online incitement, the latest incarnation of the tribalism that has long bedevilled Kenyan politics because of a potent mix of traditional animosities and socio-economic grievances.

“Some of the abusive, highly corrosive, divisive, tribal messages and blogs are criminal and this is the reason we have formed a special team,” said Francis Kimemia, the cabinet secretary, when he announced in January the creation of a government task force to monitor dangerous speech on social media.

“We are tracking all hate speakers, war mongers, and peddlers without favour with a special focus on social media and a few FM stations. We are leaving no stone unturned.”

When perpetrators are identified they will be referred for prosecution, Mr Kimemia added. “Our specialised team will work with ICT [information and communi- cations technology] and security services within and beyond to net the perpetrators and jam or cancel licences for those heinous networks.”

Kenya’s National Steering Committee on Media Monitoring has also accused bloggers of spreading hate messages, especially on major media websites. “We have written to media houses whose blogs have been receiving numerous hits, most of it ethnic hatred between two big tribes,” Mary Ombara, the committee’s secretary, told reporters in Nairobi. (In general, officials do not name specific tribes for fear of angering one or other community. The assumption is that Ms Ombara is referring to Kikuyu and Luo, the tribes of the two main rivals for the presidency.)

“Some of the messages posted on the blogs contained unprintable comments and could be classified as hate speech and incitement between two major communities,” she said, adding that authorities would trace the computers used to send the messages.

The need is urgent as Kenya prepares to elect on March 4th a successor to President Mwai Kibaki, as well as parliamentarians and new county governors. Few analysts are prepared to call the vote but most agree that another explosion of violence could be devastating for a key Western ally and East Africa’s largest economy.

The last time Kenyans voted for a leader, in late 2007, the country came to the brink of civil war. Mr Kibaki was declared the winner; his opponent Raila Odinga cried foul; and tribe turned on tribe, killing at least 1,200 people and driving hundreds of thousands from their homes.

This time, the two frontrunners are Mr Odinga, a member of the Luo tribe, and Uhuru Kenyatta, like Mr Kibaki a Kikuyu and son of Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta. Mr Kenyatta and his running mate William Ruto, a Kalenjin, are due to stand trial in April at the International Criminal Court (ICC) for their alleged role in stoking the violence five years ago. If they win the elections and refuse to go to The Hague, Kenya could face international sanctions.

Hate speech was a significant driver of the 2007 chaos, said Joel Barkan, a senior associate at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “The caustic rhetoric was disseminated by mobile phones, especially via text messages, and encouraged by talk show hosts on ethnic-language radio stations—two dominant modes of communication for Kenyans,” he wrote in a January report for the Council on Foreign Relations.

Radio broadcaster Joshua arap Sang and Francis Muthaura, the former head of the civil service, are facing trial at the ICC alongside Messrs Kenyatta and Ruto. During the last election Mr Sang was head of operations at Kass FM, which broadcasts mainly in the Kalenjin language. The ICC prosecutor alleges that he and Mr Ruto led meetings calling for the expulsion of Mr Kibaki’s supporters and used coded language on his shows to signal and broadcast the locations of the attacks.

Despite the much-vaunted but yet-to-be-proven deterrent effect of the ICC judicial sanction, calls to kill and harm are again whistling around the online space in East Africa’s most connected country. Around 36% of Kenyans have access to the internet and most use their mobile phones to get online. Kenya has an estimated 2m Facebook users and Kenyans are the second most active Twitter community in Africa, after South Africa, according to Portland, a UK-based communications consultancy.

Technology can also be a force for good: artists, students, photographers, actors, musicians and some politicians are using Twitter, blogs and Facebook to call for peace and restraint.

As flashes of violence sparked during January’s country-wide vote to choose the political parties’ nominations lists, Kenya’s Red Cross tweeted: “If we don’t give peace a chance, our children won’t have a future. Vote4Peace.”

Technology could also play a decisive role on election day by making fraud more difficult, as was the case during the 2010 referendum on the constitution, which passed peacefully thanks, in large part, to the use of electronic vote-tallying and mobile phone data transfers. It can also be used to debunk potentially inflammatory rumours.

At the iHub, Nairobi’s tech innovation nerve centre, five young Kenyans from different tribes spend eight hours a day scouring blogs and online chatrooms as part of an eight-month research project, called Umati (crowd), to track and counter the effects of hate speech.

“We thought it would be important to have a presence online and be at least holding a thermometer to the online space to see what people are inflamed about, what kind of events are causing feedback or what words are being used,” said Angela Crandall of iHub Research, who heads the project with Kagonya Awori.

The Umati team found most messages of hate in Facebook forums or in the comments sections on blogs. Twitter comments tend to be less incendiary, partly because the micro-blogging site seems to police itself, with inciters singled out for general opprobrium.

Umati’s monitors come from different tribes and search sites in their own languages—Kikuyu, Luo, Luhya, and Kalenjin, with a fifth person looking in Kiswahili and Sheng, a street slang drawn from Swahili and English. There are also plans to hire a Somali speaker—Kenya has a large community of Somali refugees as well as Somali Kenyans. Tensions with other groups have been rising, partly because of Kenya’s involvement in the war against Islamic militants in neighbouring Somalia.

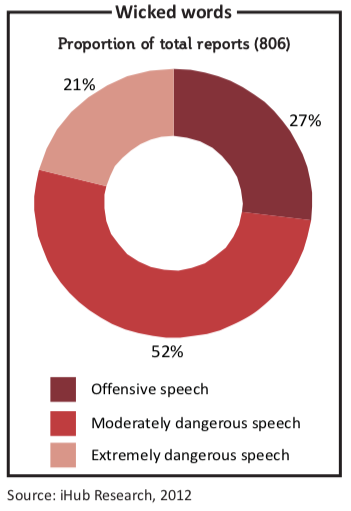

The monitors divide hate speech into offensive, moderately dangerous and extremely dangerous. Inflammatory comments are categorised according to a combination of three factors: the influence the speaker has over the audience, how inciteful the statement is to the audience, and how harmful it is to the targeted group.

Extremely dangerous speech has the highest potential to trigger violence and usually involves a call to action. Among the examples of extremely dangerous speech unearthed in November was, “I support tribalism!!! I cant vote 4 a [tribe] even at gun point.” Another comment read, “Ours is simple. Use [tribe1] to get presidency then dump them. Since when did you hear a [tribe2] appointing a [tribe1] to anything…after we win the prezzo [presidency] then we can also take their shambas [small farms] we have not forgotten.”

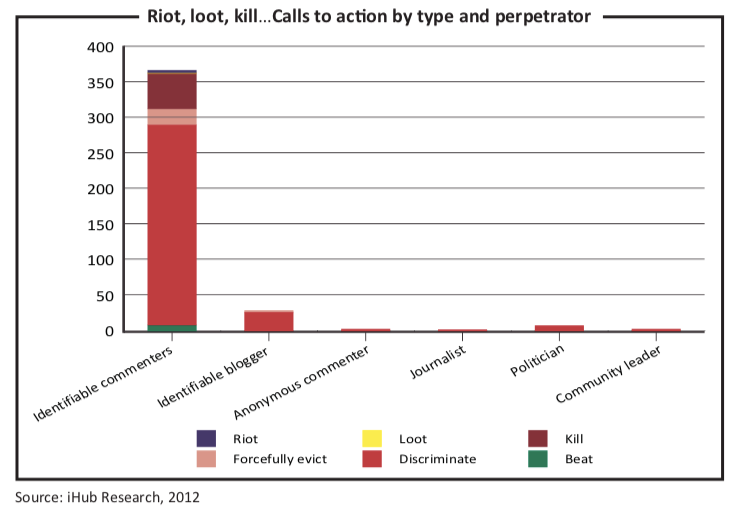

The team found more extremely dangerous speech than they expected—21% of 806 reported comments in November. They were also surprised to note that most of those engaging in such incitement were identifiable. Extremely dangerous speech is reported to Uchaguzi(choice), a technology platform mapping hate speech and other intimidation. Authorities are alerted if necessary.

“We have come across some very serious comments—some being calls to kill, to forcibly evict, to steal or beat,” Ms Awori said. “The question that worries me is, are they just talking or do they have the mettle to do what they are talking about, because if they do…then we should be worried.”

The Umati project is a collaboration with Ushahidi (witness), a non-profit, crowdsourcing platform originally set up to map reports of the 2007–08 violence. The team is also working with Professor Susan Benesch, a senior fellow who studies inflammatory speech at the World Policy Institute, a New York-based think-tank that focuses on human rights and economic development among other issues.

Umati believes that societies at risk of violence can diminish this threat—while also protecting freedom of speech—by identifying and countering dangerous speech. “I don’t believe a lot of these people are intentionally trying to go out there and push violence,” Ms Crandall said. “Some are just trying to express themselves but potentially using terms that may not be appropriate.”

Beyond these efforts to monitor hate speech, there remains the question of how to eradicate the stereotypes and animosities that feed such statements. Ms Crandall said she hopes the Umati project can provide “timely snapshots” to inform a wider debate.

“Tech itself…is usually only about 10% of the whole solution and the other 90% is other factors…We use technology as an avenue to try and address it but there are so many other things that need to be in place,” she said, citing, for example, efforts to educate people about the dangers of hate speech.

For Ms Awori, technology can serve as a starting point for a discussion that must then spread through radio and other media to reach further. The Umati project has convinced her of the need for civic education to tackle the underlying causes.

“We don’t want to say ‘no more tribes’…but teach us how to appreciate our tribe and also appreciate the next person’s tribe. This is something we should pay more attention to. We’ve been ignoring it since independence.”