Kenya: the usual suspects are running for president.

by Clar Ni Chonghaile

In a bright office in Nairobi, young Kenyan writers cluster around a mock-up of December’s issue of Shujaaz, a free comic that uses hip characters and funny storylines to educate and entertain the country’s youth. This month’s topic is election violence.

Shujaaz (or heroes in Sheng, a mix of Swahili and English) was born out of Kenya’s disputed election in December 2007. At least 1,200 people were killed in politically-motivated violence as tribe turned on tribe. Hundreds of thousands were displaced before a deal to form a coalition government between the two front-runners halted the bloodshed.

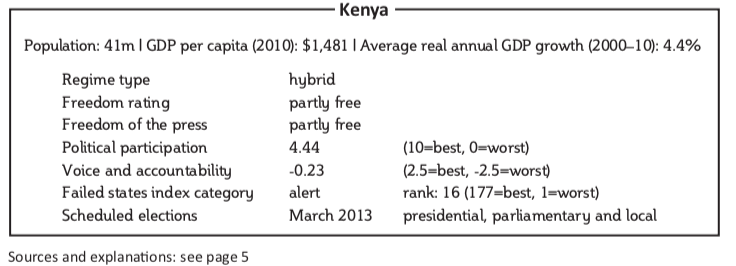

Now East Africa’s biggest economy is preparing to elect a new leader on March 4th 2013 to replace President Mwai Kibaki, who has reached the two- term limit.

The tensions that steeped Kenya in violence last time still exist. Politicians use tribal allegiances as a rallying call, violent militias offer their services for hire, and land injustices and deep poverty afflict large sections of the population.

But there are also new pressures. Four Kenyans, including two presidential hopefuls, are on trial at the International Criminal Court (ICC) for their alleged role in the 2007-08 violence; separatists are demanding the coast’s secession; and war simmers in neighbouring Somalia.

The stakes are higher than ever as Kenya expects a financial windfall from recent discoveries of oil and gas. This mix could generate the perfect political storm, with election-related violence already sparking in some volatile regions.

Under a new constitution ratified in 2010, Kenyans will now also pick governors for 47 counties, as well as senators and civic officials.

“Politics will be more localised and … that is what will likely increase tension because the corruption, ethnicity, violence and patronage that have been the bane of Kenyan politics at the national level, will be decentralised,” said Abdullahi Halakhe, an analyst at the International Crisis Group in Nairobi.

Under an accord brokered by international mediators in 2008, current Prime Minister Raila Odinga’s Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), the largest opposition at the time, joined Mr Kibaki’s Party of National Unity (PNU) in a coalition government. Mr Odinga will again try to win the presidency.

Peter Kenneth, an assistant minister and a presidential candidate himself, believes a major change is necessary. “There is no opposition,” he said. “What we have at the moment are Kenyans who disagree with what is happening. Maybe they can be termed opposition.”

Many young, educated Kenyans despise politicians who have been tainted by corruption allegations and widely condemned for repeatedly trying to award themselves hefty pay increases. Kenya’s MPs are already among the world’s highest- paid lawmakers.

Activists like Boniface Mwangi, who organised a series of graffiti paintings around Nairobi urging Kenyans to vote out “the vultures” in parliament, are calling for change. But the movement seems mainly Nairobi-based and does not have a standard-bearer.

Some of the old attitudes are intact, warned Mr Halakhe. Even the tech-savvy youth are not immune, as seen in the hate speech already appearing on Twitter and Facebook. Kenya needs a new wave of “gutsy reform activists”, he said.

What makes the Kenyan election so unpredictable, and so potentially toxic, is the importance of personalities. Candidates do not run on party policy; many have created new parties just for the March ballot. The winning candidate will need to secure 50% plus one vote in the first round to avoid a run-off round in April.

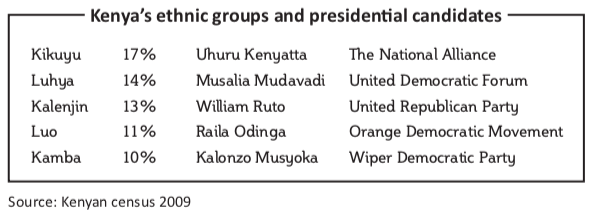

With just months to go, newspapers are full of speculation about possible alliances. It all comes down to calculating which tribe will support which personality, and which combinations can deliver victory in a country where many people vote along ethnic lines.

The main players are representatives of Kenya’s five largest groups. These are the Kikuyu, who make up 17% of the population, the Luhya at 14%, Kalenjin at 13%, the Luo at 11% and the Kamba at 10%, according to Kenya’s 2009 census.

Presidential candidates include Uhuru Kenyatta, current deputy prime minister and the son of Kenya’s founding father, Jomo Kenyatta. A Kikuyu, he is one of four Kenyans due to stand trial at the ICC in April—just when the election run-off is scheduled. Despite his ICC indictment, Mr Kenyatta is holding his own against Mr Odinga, a Luo whose supporters believe that Mr Kibaki, a Kikuyu, cheated him of victory in 2007.

Also running for president is William Ruto, a Kalenjin former minister and one- time ally of Mr Odinga. He is also due to stand trial at the ICC. Other contenders include Musalia Mudavadi, a Luhya and deputy prime minister alongside Mr Kenyatta, and Vice President Kalonzo Musyoka, a Kamba.

Judging by the tribal allegiances, none of the leading candidates has enough votes. “But if Uhuru [Kenyatta] and Ruto combine, and exploit the [ICC] persecution complex, there will be a lot going for them,” said Mr Halakhe, adding that Mr Odinga was reportedly also in talks with Mr Ruto to run on a joint ticket.

Messrs Kenyatta and Ruto have so far co-operated with the ICC, but that may end. There are signs that they may seek to gain votes by portraying themselves as victims of a foreign justice system run by outsiders.

If Mr Kenyatta were to win and refuse to go to The Hague, however, Kenya could become a pariah state like Sudan, whose leader, Omar al-

Bashir, has also been indicted by the ICC but has avoided prosecution. The question might be what price the international community would be willing to pay for stability in Kenya, a key ally in the war on terror and a regional economic heavyweight.

There is another potential twist. Rights activists have gone to court to bar Messrs Ruto and Kenyatta from standing, arguing that their candidacies are in breach of a constitutional decree on leaders’ integrity.

If Messrs Ruto and Kenyatta are disqualified, Mr Mudavadi could become a powerful contender as the leader of an “anyone but Raila” coalition with some of the remaining candidates.

Given Kenya’s history of election-related ethnic strife, and the role of the same politicians running for this election in fuelling it, violence seems inevitable.

Kenya’s coast is the biggest concern. At the heart of Kenya’s lucrative tourist industry, it has already seen riots and election-related violence as well as the arrests and killings of suspected Islamist militants with links to Somali terrorists, the Shabaab. It is also home to the separatist Mombasa Republican Council, blamed by police for a series of attacks on politicians and security officials.

Kenya needs to be freed from the “bondage of history”, Mr Kenneth said. “It’s the same people who have been there since [independence in] 1963, either them or their relatives,” he added. “If you want to develop Kenya, name and fame will not play the game. It has to be leadership that is fresh, passionate, has ability, has energy and has a vision.”

For now, the cast of characters for the upcoming poll does not promise fundamental change to this entrenched political system. Worse, it may be a recipe for repeating the last election’s devastating violence.