Yoweri Museveni, in power since 1986, is still holding on.

by Mark Schenkel

When Uganda celebrated 50 years of independence on October 9th, its president, Yoweri Museveni, promised to “deepen democratic governance”.

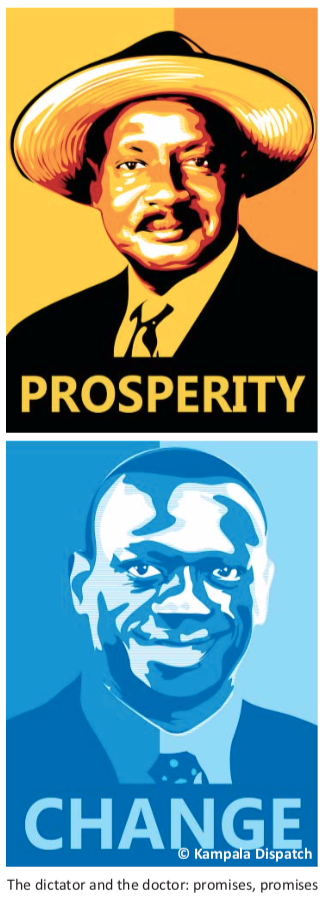

Just the opposite took place: as Mr Museveni, 68, delivered his nationwide televised speech, dozens of riot police barred his main political adversary, Kizza Besigye, 56, from leaving his home. On Uganda’s golden jubilee, its opposition leader was effectively under house arrest.

The incident illustrates Mr Museveni’s increasing authoritarianism towards his political opposition. After 26 years in power, he is Africa’s fifth longest-ruling president. Human Rights Watch, Freedom House, the International Crisis Group and others document rising cases of police brutality towards the regime’s adversaries, attacks on independent journalists and restrictions on non-governmental organisations.

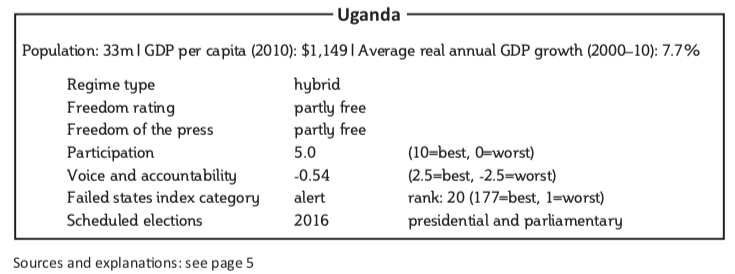

Uganda is not turning into an outright dictatorship. Political parties remain legal and Uganda holds presidential and parliamentary elections every five years (the next ones are due in 2016). The country still benefits from a vibrant and critical press. Though GDP growth per capita remained below 4% because of Uganda’s rapid population growth, this East African nation is considered one of the continent’s top economic performers with average real GDP growth of 7.7% between 2000 and 2010, according to the World Bank.

Nonetheless, the space for political change is narrowing. Aili Mari Tripp, pro- fessor of political science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the United States (US), defines Mr Museveni’s government as a “hybrid” regime: one where political competition exists but under unfair conditions. Paul Omach, a political scientist at Uganda’s Makerere University, agrees. “Museveni oversees parallel structures within government and State House that make sure he wins the elections and stays in charge,” Mr Omach says.

Mr Museveni relies increasingly on patronage and the police to keep his grip on power, Mr Omach explains. He has nearly doubled the number of government districts, from 60 in 2001 to 110 today, thereby creating additional political posts whose holders can be bribed to boost his local support. Mr Museveni spent a “particularly high” amount of money on campaigning and outright vote-buying before the last elections in February 2011, claims Joel D. Barkan from the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in the US. There is also growing suspicion that the police are out to frustrate the opposition through random arrests.

Paradoxically, the opening up of space for the political opposition was instrumental for Mr Museveni’s strategy to remain in office. From his rise to power in 1986 until 2005, Uganda lacked a legal opposition. The ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) was supposed to function as an all-inclusive umbrella encompassing politicians from all persuasions who would compete on the basis of personal merit instead of ethnic loyalty. This “no-party” system, Mr Museveni argued, was to prevent the re-emergence of the divisive, tribal, multiparty politics that allegedly paved the way for the bloodshed under the former presidents Milton Obote and Idi Amin between 1966 and 1986.

This changed in 2005 when the NRM-dominated parliament allowed Ugandans to vote for the reintroduction of multiparty politics. Uganda, Mr Museveni said, had become politically mature. In reality, Mr Omach argues, Mr Museveni was more concerned about appeasing the growing number of critics—many from within his own party—who denounced the government’s increasing cronyism and corruption. One prominent critic was Mr Besigye, Mr Museveni’s personal physician during the liberation struggle and then a government minister and an army colonel before quitting the NRM.

Mr Museveni’s multipartyism defused some of the criticism towards government. More importantly though, he used the move as a bargaining chip for lifting presidential term limits, thus staying in office. “Museveni knew very well that he could safely open up the political space because the newly-established opposition would not be able to operate effectively, given the president’s extra-parliamentary ways to retain his hold on power,” Mr Omach says.

The first multiparty elections in 2006 proved that regime change through the ballot box was going to be difficult. Mr Besigye—by now leader of the opposition party Forum for Democratic Change (FDC)—spent most of his time in court contesting trumped-up charges. After losing elections again in 2011, Mr Besigye opted for an extra-parliamentary strategy. Together with the advocacy group Activists 4 Change (A4C), he launched demonstrations in the capital, Kampala, against the steep rise in the cost of living and bad governance. In April 2011 at least nine protesters died in street battles with the police. A year later authorities outlawed A4C. The group has since resurfaced as For God and My Country.

“Besigye basically says: ‘If you don’t allow us to strive for political change through parliament then you only leave us with the option of doing it by creating chaos and making this country ungovernable,’” Mr Omach says. It is a risky strategy as many tradespeople and shop owners in Kampala dislike the violence and disorder, analysts say, even if they blame the police for using excessive force.

The opposition lacks an alternative vision and is divided. Many FDC politicians are former NRM members who have fallen out with the ruling party. Ugandans suspect that these politicians act more for personal gain than out of patriotism. Ahead of last year’s elections, the FDC teamed up with four other parties, including the late Milton Obote’s

Uganda People’s Congress. The coalition soon collapsed. The opposition’s weaknesses partially explain why Mr Museveni won 68% of the vote against Mr Besigye’s 26% in 2011. Still, some hold out hope that political change can come through the ballot box.

Angelo Izama, a Ugandan writer and political analyst, praises Mr Besigye for creating “a political opposition within the existing system, first by pushing Mr Museveni to re-introduce multiparty politics, then by putting pressure on government through street protests. Change comes about gradually. At least we are not a one-party state anymore.”

By making government appear as if it is not entirely in control, Mr Besigye’s street protests have contributed to a growing political awareness among Ugandans. “The more people see what’s going on, the less tolerant they become of the current way of staying in power,” Mr Izama adds.

“The stories about corruption and mismanagement put pressure on the bureaucracy and even create opposition within the NRM,” he says. That is especially true for the younger parliamentarians who hardly identify with Mr Museveni’s nearly 30-year-old claim of having brought peace and stability to Uganda.

Mr Omach, however, fears that Mr Museveni and his narrowing circle of loyalists will not relinquish power easily. He does not rule out a Zimbabwe-like scenario: a liberation president undoing his own achievements and careening towards oppression. “Ultimately, this may bring renewed instability,” Mr Omach says.

With Mr Besigye set to step down as the FDCleader, Mr Omach hopes that a new opposition leader will refocus on bringing about political change through parliament instead of popular protests. The main contestants are Nandala Mafabi, the current FDC leader in parliament, and Mugisha Muntu, a former military officer and NRM member. “Both Muntu and Mafabi tend towards the parliamentary way … with Muntu seeming to me more elitist,” Mr Omach says, while “Mafabi also knows how to play the streets.”